Spewing

hot clouds of gas and bulging with lava, Mount Merapi, one of Indonesia's most

active volcanoes, has rumbled to life, and a full-scale eruption is imminent,

local officials warn.

Spewing

hot clouds of gas and bulging with lava, Mount Merapi, one of Indonesia's most

active volcanoes, has rumbled to life, and a full-scale eruption is imminent,

local officials warn.

Spewing

hot clouds of gas and bulging with lava, Mount Merapi, one of Indonesia's most

active volcanoes, has rumbled to life, and a full-scale eruption is imminent,

local officials warn.

Spewing

hot clouds of gas and bulging with lava, Mount Merapi, one of Indonesia's most

active volcanoes, has rumbled to life, and a full-scale eruption is imminent,

local officials warn.

"The wait is on for larger events," says John Pallister, a geologist with the joint U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)-USAID Volcano Disaster Assistance Program. Now, the main concern is making sure that the local people living on the volcano's flanks are out of harm's way.

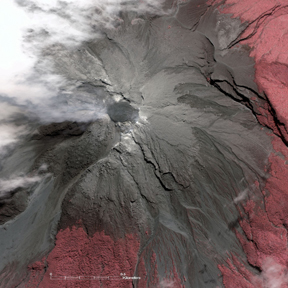

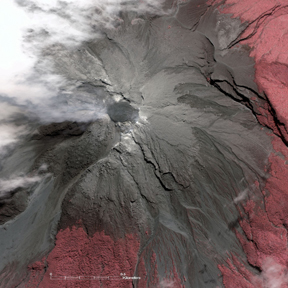

A new lava dome began growing at the

summit of Indonesia's Mount Merapi in early May. On May 13, Indonesian volcanologists

raised the volcano alert to the highest level, requiring local villagers living

within 12 kilometers of the summit to evacuate. Image is courtesy of U.S. Geological

Survey, copyright of GeoEye.

Many of the Javanese people living on Mount Merapi's fertile slopes are skeptical

of the volcano's danger, believing that Merapi, looming more than 2,900 meters

above central Indonesia, is a sacred, if temperamental, place. Referring to

an eruption, or even calling the mountain by name, is taboo. But as the volcano

begins to send deadly hot clouds of ash and steam, locally called wedhus

gembel or "shaggy goats," speeding down the volcano's slopes,

Indonesian scientists are now urgently advising the local populace that Merapi

is on the verge of a full-scale eruption.

The country's volcanologists have kept a close watch on the restless volcano for the past five years — a period of unusual quiet for Merapi, which has historically erupted every one to two years, Pallister says.

However, in August, scientists at Indonesia's Directorate of Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation noted increased seismic activity at the volcano and warned the local people about Merapi's continuing hazards, "to tell [them] that the volcano hasn't gone to sleep," Pallister says.

On April 12, the Indonesian scientists recorded another significant increase in seismic activity and raised the volcano alert level to its second highest stage, a standby status that indicates that it might erupt at any time. Shortly after, on April 18, scientists at nearby Yogyakarta's Volcano Technology Development and Education Agency, located 30 kilometers south of Merapi, observed the volcano sending clouds of thick white sulfurous smoke 400 meters into the air. Two weeks later, the first streams of lava began to flow down the mountain's sides. The agency also recorded both volcanic and multi-phase tremors, indicating a buildup of strong magma pressure in the volcano's crater, reported Subandriyo, a geologist with the Yogyakarta agency's Merapi Volcano Observatory, to Deutsche Presse-Agentur.

More telltale signs of an imminent eruption continue to appear. In early May, scientists observed a glowing dome of lava rapidly growing at the volcano's peak. That dome, covering a 100-meter-wide bulge of hot magma, indicates the type of eruption to come, they say: Instead of a single massive explosion, the dome's eventual collapse will send the searingly hot ash and steam clouds, known to volcanologists as pyroclastic flows, speeding down the volcano's flanks. This type of eruption — the collapse of a bulging lava dome that triggers these flows — is typical of this volcano, so much so that it is known as a "Merapi style of volcanism," says geologist Jim Vallance of USGS' Cascades Volcano Observatory.

"The good news is [these types of eruptions] don't produce the same widespread

damage as more explosive events" such as the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption,

Pallister says. "But their focused impacts are deadly." During the

volcano's most recent eruption in 1994, for example, pyroclastic flows reached

temperatures of up to 600 degrees Celsius and flew down the mountain at more

than 100 kilometers per hour, killing 66 people.

A first wave of those flows sped down the volcano's flanks Monday, only two days after the Indonesian agency raised the alert to its highest stage and began to enforce mandatory evacuations of the villagers within the hazard zone, which extends to about 12 kilometers from the summit. "The dome at the summit has grown over the last few days and is now beginning to collapse in several directions," Pallister says.

The initial flows only extended as far as 3 to 4 kilometers. However, the question is when the collapses of the dome at the summit will feed larger pyroclastic flows, which could extend at least twice as far and into populated village areas, he says. The dome, located at the summit, is continuing to grow at a rate of about 150,000 cubic meters per day, and currently contains about 2 million cubic meters of magma.

Although mandatory evacuations are now in place, "the challenge will be how long people will be willing to stay away" while the dome continues to grow, Pallister says. Despite the efforts of the Indonesian volcanology agency, many villagers have been reluctant to leave their livestock and farms, and deep-seated beliefs about the mountain have led to skepticism of the geological warning signs, according to a May 11 report in Indonesia's Jakarta Post.

Indonesia is part of the "Ring of Fire," the

most volcanically and seismically active region on Earth, which forms a rough

circle of multiple subduction zones and other plate boundaries around the margins

of the Pacific Ocean. Home to more than 100 active volcanoes,

the country sits atop a subduction zone, where the Indo-Australian plate dives

under the overlying Eurasian plate. The subduction also formed the 6- to 7-kilometer-deep

Java Trench, situated in the Indian Ocean off Indonesia's southern coast.

Merapi's deadliest recorded eruption occurred in 1930, killing 1,369 people.

Carolyn Gramling

Links:

Merapi

Volcano Observatory

Map

of Indonesia's Volcanoes

The

Ring of Fire

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |