Geotimes

Web

Extra

November 15, 2001

Biogeochemistry

Genetic

sequencing at sea

Last month, ocean scientists

put new biotechnologies to the test -- performing the first-ever DNA sequencing

at sea. Over the course of a 17-day research cruise aboard the research vessel

Atlantis, scientists sequenced just under 2 million base pairs of DNA

from different microbes and organisms that live in and around deep-sea hydrothermal

vents. "What we're trying to do is actually link the organism and its genetics

with the environment," says Craig Cary, a marine biologist at the University

of Delaware and the research team leader.

Cary's

team conducted daily dives aboard the submersible Alvin into the waters

some 1,200 miles off the coast of Costa Rica to collect microbes, tubeworms,

vent crabs and other life forms that thrive in vent environments reaching temperatures

of 750 F. Of particular interest to their research is the Pompeii worm. Covering

the worm's back, Cary says, is a "fleece of bacteria." These microbes

may possess heat-stable enzymes useful in a variety of applications, such as

pharmaceutical production, food processing, paper and textile manufacture, and

hazardous waste cleanup. "The sequencing that we're doing and that will

be done continuously was really to understand how geochemistry is motivating

and moving the bacterial community," Cary says.

Cary's

team conducted daily dives aboard the submersible Alvin into the waters

some 1,200 miles off the coast of Costa Rica to collect microbes, tubeworms,

vent crabs and other life forms that thrive in vent environments reaching temperatures

of 750 F. Of particular interest to their research is the Pompeii worm. Covering

the worm's back, Cary says, is a "fleece of bacteria." These microbes

may possess heat-stable enzymes useful in a variety of applications, such as

pharmaceutical production, food processing, paper and textile manufacture, and

hazardous waste cleanup. "The sequencing that we're doing and that will

be done continuously was really to understand how geochemistry is motivating

and moving the bacterial community," Cary says.

[Previous University of Delaware research

confirmed that the Pompeii worm is the most heat-tolerant animal on Earth. Covering

this deep-sea worm's back is a fleece of bacteria. Courtesy of University

of Delaware College of Marine Studies.]

Previously, studying these

extreme, deep-sea environments proved difficult, because of time and technological

limitations in the field, Cary says. But now, with the MegaBACE 1000 DNA Analysis

System and the TempliPhi DNA Sequencing Template Amplification Kit from Amersham

Biosciences, they "were able to break a barrier that had always been in

place" to analyze the specimens' DNA as Alvin collected them and

brought them up to the surface.

Two scientists from Amersham

Biosciences conducted the DNA analysis using the company's sequencing systems,

the same technologies used in the Human Genome Project, but with some added

features to allow for the maritime application. "What was missing were

some of the steps in the laboratory to get the samples ready for sequencing,"

says Bob Feldman, production sequencing and collaborations manager at Amersham.

The application process, however, "shortens the whole process down to a

matter of only about a day, so that you can collect your organisms, make your

DNA and then basically just start sequencing right away. You don't have to spend

another three or four days and another three or four more pieces of equipment

to get things ready to go into sequencing," Feldman says.

Both

Cary and Feldman say this kind of research is part of a new way of studying

creatures and their ecosystems in the field. Cary says he hopes to continue

the research with more field analyses next November. The National Science Foundation

funded the research. Although the expedition has ended, the expedition Web site

is still online at www.ocean.udel.edu/extreme2001.

Both

Cary and Feldman say this kind of research is part of a new way of studying

creatures and their ecosystems in the field. Cary says he hopes to continue

the research with more field analyses next November. The National Science Foundation

funded the research. Although the expedition has ended, the expedition Web site

is still online at www.ocean.udel.edu/extreme2001.

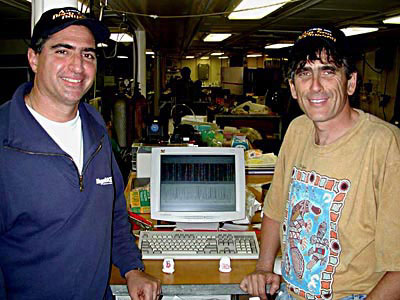

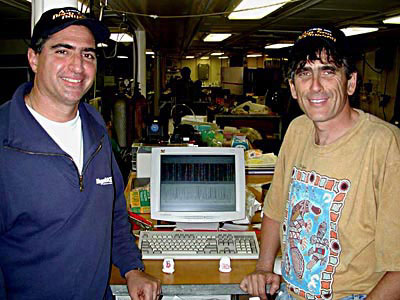

[Robert Feldman (left), of Amersham Biosciences,

and Craig Cary (right), University of Delaware marine

biologist and chief scientist for the Extreme 2001 expedition, in the lab on

board the R/V Atlantis.

Courtesy of University of Delaware College of Marine Studies.]

Lisa M. Pinsker

Cary's

team conducted daily dives aboard the submersible Alvin into the waters

some 1,200 miles off the coast of Costa Rica to collect microbes, tubeworms,

vent crabs and other life forms that thrive in vent environments reaching temperatures

of 750 F. Of particular interest to their research is the Pompeii worm. Covering

the worm's back, Cary says, is a "fleece of bacteria." These microbes

may possess heat-stable enzymes useful in a variety of applications, such as

pharmaceutical production, food processing, paper and textile manufacture, and

hazardous waste cleanup. "The sequencing that we're doing and that will

be done continuously was really to understand how geochemistry is motivating

and moving the bacterial community," Cary says.

Cary's

team conducted daily dives aboard the submersible Alvin into the waters

some 1,200 miles off the coast of Costa Rica to collect microbes, tubeworms,

vent crabs and other life forms that thrive in vent environments reaching temperatures

of 750 F. Of particular interest to their research is the Pompeii worm. Covering

the worm's back, Cary says, is a "fleece of bacteria." These microbes

may possess heat-stable enzymes useful in a variety of applications, such as

pharmaceutical production, food processing, paper and textile manufacture, and

hazardous waste cleanup. "The sequencing that we're doing and that will

be done continuously was really to understand how geochemistry is motivating

and moving the bacterial community," Cary says.

Both

Cary and Feldman say this kind of research is part of a new way of studying

creatures and their ecosystems in the field. Cary says he hopes to continue

the research with more field analyses next November. The National Science Foundation

funded the research. Although the expedition has ended, the expedition Web site

is still online at

Both

Cary and Feldman say this kind of research is part of a new way of studying

creatures and their ecosystems in the field. Cary says he hopes to continue

the research with more field analyses next November. The National Science Foundation

funded the research. Although the expedition has ended, the expedition Web site

is still online at