About 65 million

years ago, a huge chunk of rock and ice came screaming into Earth’s atmosphere,

slammed into the Yucatan Peninsula, vaporized water and sent a huge mass of

high-energy particles and ash up into the atmosphere. Within several days, the

returning particles created the iridium-rich layer that marks the Cretaceous-Tertiary

(K/T) boundary in Earth’s geologic history. The particles also set fire

to the vegetation in the region of impact, and probably halfway around the world

as well, according to research published in the Aug. 30 Journal of Geophysical

Research.

About 65 million

years ago, a huge chunk of rock and ice came screaming into Earth’s atmosphere,

slammed into the Yucatan Peninsula, vaporized water and sent a huge mass of

high-energy particles and ash up into the atmosphere. Within several days, the

returning particles created the iridium-rich layer that marks the Cretaceous-Tertiary

(K/T) boundary in Earth’s geologic history. The particles also set fire

to the vegetation in the region of impact, and probably halfway around the world

as well, according to research published in the Aug. 30 Journal of Geophysical

Research.At a K/T boundary site in the Raton Basin, David Kring points to a light-colored layer of debris that marks the K/T boundary. The layer contains bits and pieces of Mexico that were launched from the Chicxulub impact crater. Photo by Dan Durda.

The extent of fire damage after the K/T impact has been a point of contention in the past. In their model, planetary geoscientists David Kring of the University of Arizona in Tucson and Daniel Durda of the Southwest Research Institute’s Space Studies Department in Boulder, Colo., show that the impact delivered enough heat to ignite even wet vegetation near the Chicxulub crater where the meteor or bolide hit. Indeed, they show that the material sent high into the atmosphere traveled to the opposite side of the globe, where it fell, still hot enough to deliver about 12.5 kilowatts of energy per square meter.

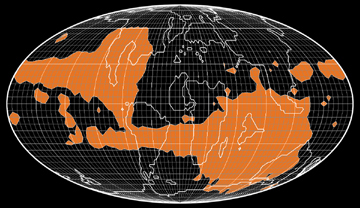

Kring and Durda suggest searching for charcoal evidence of fires, rather than using the distribution of soot to determine the trajectory of the bolide. Conservative estimates for the model, Kring says, indicate that wildfires started across the equator and Indian subcontinent, spreading globally. “The uncertainties are the trajectory impact,” he says. For example, if the impact traveled from southwest to northeast, Europe would also catch fire.

Wendy

Wolbach, professor at DePaul University and a leading specialist on wildfires

related to the Chicxulub impact, called the results very exciting. “When

we first came out with the theory, people didn’t think fires could be triggered

directly by an impact,” she says. “[Kring and Durda’s study]

basically confirms a model that there is enough power given off by the impact

to start fires, and that you can start fires on more than one continent.”

Wendy

Wolbach, professor at DePaul University and a leading specialist on wildfires

related to the Chicxulub impact, called the results very exciting. “When

we first came out with the theory, people didn’t think fires could be triggered

directly by an impact,” she says. “[Kring and Durda’s study]

basically confirms a model that there is enough power given off by the impact

to start fires, and that you can start fires on more than one continent.”

The map illustrates where surface temperatures were high enough to ignite vegetation after the impact event at the K/T boundary. The land-based areas that are orange are regions where scientists suggest searching for charcoal evidence indicating trajectory of the impact event. Image by D. Kring and D. Durda.

Naomi Lubick

Geotimes contributing writer