Geotimes

Feature

Global Petroleum

Resources: A View to the Future

Thomas S. Ahlbrandt and Peter J. McCabe

Sidebars:

Oil in the Caspian

Oil in Iraq

Geologists are often asked: How much oil and gas are left in the world?

There is no simple answer to this question. Geology, economics, politics, technology

and social science all play a role in assessing our resources and determining

the economic viability of those resources.

The terms petroleum, crude oil, natural gas and natural gas liquids each have

precise scientific definitions. But appending the word resource to any of them

creates a term that crosses the boundary between science and social science and

includes economics. Many geologists begin to feel uncomfortable in this area between

science and social science. Webster’s Dictionary defines a resource

as “a natural source of wealth or revenue.” A fossil fuel resource is

one that can be profitably extracted. Compared to scientific terms, social science

terms are fluid. What is profitable or societally acceptable one day may not be

the next and vice versa. We must ask: How much profit is necessary for extraction?

What time frame are we considering?

USGS estimate of petroleum resources

It is necessary to periodically reassess petroleum resources, not only because

new data become available and better geologic models are developed; but also

because many non-geologic factors determine which part of the crustal abundance

of petroleum will be economic and acceptable over the foreseeable future.

In 2000,

the U.S. Geological Survey completed an assessment of the world’s conventional

petroleum resources, exclusive of the United States. This assessment is different

from those before it: Overall the 2000 assessment of potential petroleum resources

is higher than previous assessments, largely because it is the first USGS world

assessment to include field growth estimates.

In 2000,

the U.S. Geological Survey completed an assessment of the world’s conventional

petroleum resources, exclusive of the United States. This assessment is different

from those before it: Overall the 2000 assessment of potential petroleum resources

is higher than previous assessments, largely because it is the first USGS world

assessment to include field growth estimates.

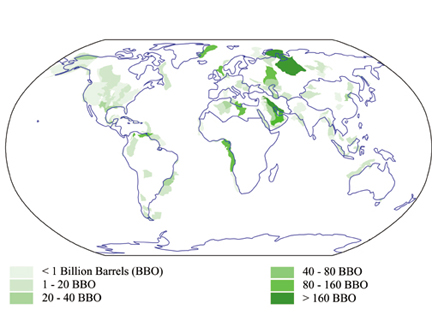

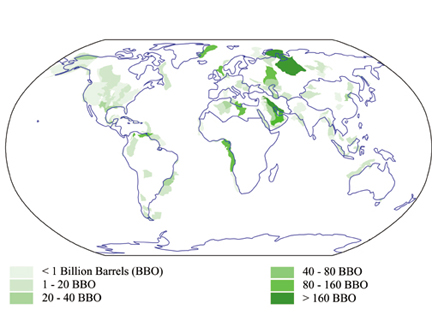

The world’s

oil: Conventional oil endowment (cumulative production plus mean estimates

of remaining oil reserves and undiscovered oil resources) by province in billion

barrels of oil (BBO) for 128 oil provinces. World data are from the U.S. Geological

Survey (USGS) 2000 assessment of world petroleum resources; U.S. data are from

USGS (1995 assessment) and from the Minerals Management Service (1996 assessment).

USGS image.

Based on a thorough investigation of the petroleum geology of each province,

the assessment couples geologic analysis with a probabilistic methodology to

estimate remaining potential. Including the assessment numbers for the United

States from USGS and the Minerals Management Service (MMS), the world’s

endowment of recoverable oil — which consists of cumulative production,

remaining reserves, reserve growth and undiscovered resources — is estimated

at about 3 trillion barrels of oil. Of this, about 24 percent has been produced

and an additional 29 percent has been discovered and booked as reserves. The

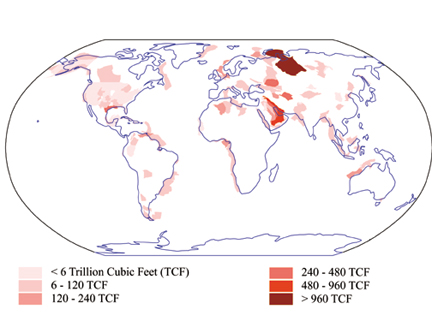

natural gas endowment is estimated at 15.4 quadrillion cubic feet (2.5 trillion

barrels of oil equivalent), of which only about 11 percent has been produced

and an additional 31 percent has been discovered and booked as reserves.

The USGS assessment is not exhaustive, because it does not cover all sedimentary

basins of the world. Relatively small volumes of oil or gas have been found

in an additional 279 provinces, and significant accumulations may occur in these

or other basins that were not assessed. The estimates are therefore conservative.

Areas that contain the greatest volumes of undiscovered conventional oil include

the Middle East, western Siberia, the Caspian region, and the Niger and Congo

deltas. Significant undiscovered oil resource potential was suggested in a number

of areas that do not have important production history, such as northeast Greenland

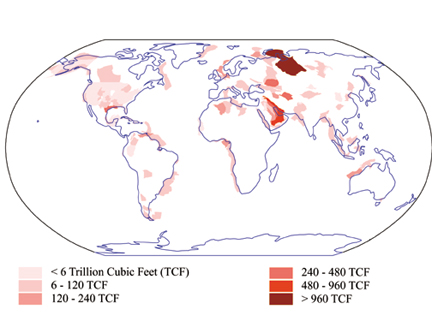

and offshore Suriname. Areas that contain the greatest volumes of undiscovered

conventional gas include the West Siberian Basin, the shelves of the Barents

and Kara Seas, the Middle East and offshore Norway. Significant additional undiscovered

gas resources may occur in a number of areas where large discoveries have been

made but remain undeveloped. Examples include East Siberia and the Northwest

Shelf of Australia. About half of the assessed undiscovered petroleum potential

of the world is offshore, especially outside the established provinces of the

United States, former Soviet Union, Middle East and North Africa. Arctic basins,

which hold about 25 percent of the undiscovered petroleum resources, make up

the next great frontier.

The assessment

suggests that some recent claims of an imminent oil shortage cannot be supported.

Furthermore, large volumes of natural gas can replace oil in most market sectors.

The rate of production of resources depends on many factors, including investments

in exploration and development, political conditions and the growth or decline

in demand from the global economy.

The assessment

suggests that some recent claims of an imminent oil shortage cannot be supported.

Furthermore, large volumes of natural gas can replace oil in most market sectors.

The rate of production of resources depends on many factors, including investments

in exploration and development, political conditions and the growth or decline

in demand from the global economy.

The world’s

gas: Gas endowment (cumulative production plus mean estimates remaining

of oil reserves and undiscovered natural gas resources) by province, in trillions

of cubic feet of gas (TCF) for 128 gas provinces. Note that 6 TCF equal 1 BBO

in energy equivalent units. World data are from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

2000 assessment; U.S. data are from USGS (1995 assessment) and the Minerals

Management Service (1996 assessment). USGS image.

It is impossible to forecast rates of production purely from geologic information.

Given this fact, it does appear likely that the global production from conventional

oil accumulations identified in the USGS 2000 assessment will be in decline

before the middle of the century. The relative abundance of natural gas will

encourage its substitution for oil in some market sectors. Advancements in new

technologies — such as gas-to-liquids and various hydrogen-based systems

that extract hydrogen from methane — will facilitate this substitution.

The Middle East

The USGS assessment of undiscovered oil resources for the Middle East was higher

than previous assessments. This new estimate is based on detailed petroleum

migration modeling that integrated geochemical data with recently acquired structure

and seismic data. The Jurassic has both rich source rocks and carbonate reservoirs.

Cretaceous and Tertiary reservoirs trap hydrocarbons in a currently generating

petroleum system. Several significant evaporite seals and active trap formations

also provide favorable factors for future potential.

Supergiant discoveries — those exceeding 1 billion barrels — have

been found recently in the Azadegan field of Iran and in the Kra Al Maru field

of Kuwait. Many new discoveries in Saudi Arabia on the flanks of Ghawar and

in Paleozoic reservoirs are also very encouraging.

Significant oil potential is found in many areas of the former Soviet Union.

The West Siberian Basin remains prolific. The Caspian region is active with

enormous discoveries (at least 20 billion barrels) of oil in the Kashagan field

in Paleozoic carbonates. Another recent supergiant discovery is the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli

complex (at least 5 billion barrels).

The entire south Atlantic, both in the offshore of West Africa and eastern Brazil

have experienced substantial discoveries in deepwater clastic deposits and will

continue to do so as evidenced by new discoveries in the Santos Basin.

The challenges of developing resources

While petroleum resources in the world are plentiful, their distribution is

uneven. Much of the world’s oil and gas is distant from the major markets

— a continuing concern for political, economic and environmental reasons.

Many of the offshore and arctic areas are environmentally sensitive, far from

markets, and in environments hostile from an engineering perspective. Developing

these regions will require international cooperation among governments, environmentalists

and the petroleum industry to a degree not previously seen.

Existing export and import patterns will inevitably change over the next few

decades. In particular, results of the USGS study suggest that it may be difficult

to sustain U.S. oil imports from Mexico and natural gas imports from both Canada

and Mexico. For example, the USGS estimates for technically recoverable, conventional

natural gas resources in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin are an order of

magnitude lower than previous Canadian assessments of the region. Recent Canadian

assessments have been lowered. The differences among assessments are related

to the minimum size at which a field is considered economically viable. Smaller

fields are more numerous than larger fields. The smallest field size that USGS

considered viable on a world scale was 3 billion cubic feet of gas for a Canadian

gas pool.

Although many energy scenarios call for increased natural gas consumption in

the United States, we may need to increase imports of liquefied natural gas

or make major domestic natural gas discoveries to meet this new demand. Currently,

the United States imports about 15 percent of its natural gas from Canada.

Many organizations and individuals regard the USGS 2000 assessment as the most

credible and scientific world petroleum assessment available. However, assessments

are dynamic and each represents a snapshot in time. It is worth considering

the evolution of some of the non-geologic factors that necessitated a revision

from previously published USGS assessment numbers. Because these parameters

are still evolving, we can also speculate how they may impact future assessments.

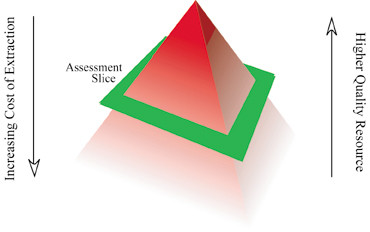

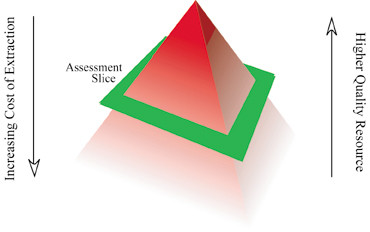

The resource pyramid

In an

abstract way, the amount of oil or gas in the world can be viewed as a pyramid

with a small amount of high quality resource that is cheap to extract, and with

increasing amounts of lower quality resource that cost more to extract. The

upper part of the pyramid is well defined, as these resources are mostly known

and are generally considered “conventional.” The lower part of the

pyramid is less well understood and the amount of petroleum in accumulations

that are now largely uneconomic — such as hydrates or basin-centered gas

— is highly speculative. An assessment draws a slice through the pyramid

defining the resource of oil or gas that is estimated to become economic within

the foreseeable future.

In an

abstract way, the amount of oil or gas in the world can be viewed as a pyramid

with a small amount of high quality resource that is cheap to extract, and with

increasing amounts of lower quality resource that cost more to extract. The

upper part of the pyramid is well defined, as these resources are mostly known

and are generally considered “conventional.” The lower part of the

pyramid is less well understood and the amount of petroleum in accumulations

that are now largely uneconomic — such as hydrates or basin-centered gas

— is highly speculative. An assessment draws a slice through the pyramid

defining the resource of oil or gas that is estimated to become economic within

the foreseeable future.

The resource pyramid:

The pyramid charts the economic feasibility of an area’s petroleum

reserves. It shows a small volume of prime resource at top and, at bottom, larger

volumes of lower quality resources that are more expensive to extract. The amount

and nature of occurrence of oil and gas near the base of the pyramid is not

well understood. Assessments slice through the pyramid, defining only resources

that have economic potential within the foreseeable future. USGS image.

Over time, the relative positions within the pyramid of the various accumulations

of the world’s oil and gas vary. The geological abundance of petroleum

(prior to extraction) remains the same, but our perception of it changes for

a variety of reasons. Hydrocarbon accumulations that were once thought to be

only of scientific interest are transformed into “unconventional resources”

and eventually become “conventional” as they rise higher in the pyramid.

For example, the recovery costs for oil from Alberta’s oil sands have fallen

dramatically over the last 20 years and are now about $8 per barrel. By 2005,

fully 10 percent of North America’s oil production will come from Alberta’s

oil sands.

The Alberta oil sands contain 1.6 trillion barrels of oil, of which 311 billion

barrels are recoverable with current technology. Similarly, a significant amount

of U.S. natural gas production now comes from sources once considered unconventional

but now viewed as conventional. Resources may also fall in the pyramid. In 1860,

Titusville was the oil resource at the top of the pyramid. In 1901, Spindletop

was. Although they still produce, western Pennsylvania and eastern Texas are

no longer near the top of the pyramid. At the beginning of the 20th century,

the Middle East as an oil resource was viewed at the bottom of the pyramid.

Elements influencing the

pyramid

The human and social factors affecting data and information incorporated into

a resource assessment can be viewed schematically as a sphere of interacting

factors that circle outside the pyramid and act on it. In large part, these

factors determine the relative position of various petroleum accumulations within

the pyramid and ultimately determine what a viable petroleum resource is. Human

and social factors are dynamic and appear to change at an ever-increasing pace.

USGS gains insights into potential future viable resources related to these

factors by talking with petroleum industry leaders.

Elements affecting the pyramid are:

Geoscience Technology

The last decade has seen rapid advances in the science and technology of oil

and gas exploration and production. Global, satellite-derived data and detailed

topographic and spectral images allow us to see our planet as never before.

Deep seismic data and earth tomography allow us to perceive the structure of

the planet. The digital revolution and the personal computer have put our own

data and vast amounts of public domain data at our fingertips. Two key technologies

have enhanced our ability to “see” the subsurface realm: 3-D seismic

reflection data and DHIs (Direct Hydrocarbon Indicators determined from seismic

attributes) viewed in visualization centers. More sensitive and precise logging

and geochemistry tools provide new insights. Recent research also has given

us more clues about fluid flow and hydrocarbon migration.

Petroleum Engineering and Chemistry

The drilling and completion of wildcat tests and production wells have advanced

rapidly in the last decade. Drilling in deep water in the Arctic and other hostile

environments has allowed the industry to venture into regions once thought “out

of reach.” Long horizontal reach wells — which stretch laterally up

to several kilometers, extend the reach of drilling and enhance recovery —

have become common. Well stimulation and improved fracing technologies —

which increase the rate of petroleum flow from a reservoir by injecting hydraulic

fluids to fracture the rocks — have greatly increased recovery factors

and improved recovery economics for many accumulations.

Extraction of heavy oil, tight gas and coalbed methane is now economically viable

in North America, but still considered “unconventional” in many parts

of the world. The increasing ability to process huge data sets promises advanced

models of fluid flow and geochemistry that will continue to improve the ability

to identify prospects, and will help to boost recovery factors. A small percentage

rise in recovery factors worldwide would increase recoverable oil and gas resources

considerably.

The International Oil and Gas

Business

The complex interrelations of national oil companies, large international integrated

energy companies, and independent operators all contribute to our perceptions

of world oil and gas resources. Sanctions, subsidies, taxes, regulations and

environmental policies all impact the potential availability of resources and

our relative understanding of them. Despite all of our geological expertise,

much oil and gas is still found by drilling, and if large geographic areas are

“off limits” for long periods, there is no chance of serendipitous

discoveries.

Gas is assuming a more prominent role in the petroleum industry. Much needs

to be learned about the viability of unconventional gas deposits such as coalbed

methane, tight gas, fractured shale gas, gas hydrates and dissolved saltwater

gas. We have many questions to answer: Can we effectively find and produce these

dispersed, low concentration hydrocarbons? Will markets be found for geographically

stranded gas? If a coalbed methane accumulation is found in Siberia, is it a

reserve, a resource or something that has no potential to be developed within

the foreseeable future?

The Political Domain

Thirty years ago it was common to speak of the “500 sedimentary basins”

of the world. At that time, the Cold War divided the world, and most western

geoscientists knew little of eastern block basins. Now we speak of more than

1,500 sedimentary basins worldwide. Political agendas and policies have a major

impact on whether or not a particular hydrocarbon accumulation is considered

a resource. Regulations, environmental policies, subsidies and economic agendas

in one region may have a global impact.

Global Economics

In the competitive petroleum business of finding and producing oil and gas,

performance is measured by the value created. The energy business floats on

an economic sea of high and low tides and periodic storms. The health of the

global economy, the price of oil, and cycles of demand and oversupply raise

and lower all boats. In such dynamic, commodity-driven environments, the definition

of a resource changes with time and market conditions.

The Human Element

A critical component in the resource equation is the human mind. The mind can

create models of the dynamic subsurface realm and intelligently estimate the

resource base. But we face two problems. In this time of prodigious quantities

of data and information, the number of knowledgeable and experienced oil finders

is decreasing because fewer are being trained. The annual survey of universities

conducted by the American Geological Institute shows that the number of geoscience

degrees granted in 2001 was a third of the number granted 20 years ago.

The second problem is that the average citizen has little knowledge of the subsurface

realm and even less about the fluid dynamics of oil and gas deposits. Thus,

most policymakers and users of energy are not equipped to enter the debate about

the nature of the world’s oil and gas resources. As a consequence, the

debate often has migrated to the end members — Malthusians and Cornucopians

— each one with a set of personal, corporate, political or environmental

agendas. In large part, it is a misunderstanding of the nature of resources

that allows those with agendas to argue vehemently over the size of remaining

resources.

The resource pyramid will continue to evolve. An understanding of the geological,

technological, economic, political and social forces that drive that change

is critical to understanding resources. Raw oil and gas resource numbers, used

out of context, are the shot and powder of manipulators. The economic petroleum

geoscientist must clearly be at the table when corporate managers, politicians,

lawyers, economists and activist groups discuss world energy resources.

View the USGS

assessment online.

Ahlbrandt

and McCabe are research geologists with

the U.S. Geological Survey in Denver. The authors thank Art Green of ExxonMobil

Exploration Co. for many stimulating discussions over the last few years on the

factors influencing the resource pyramid.

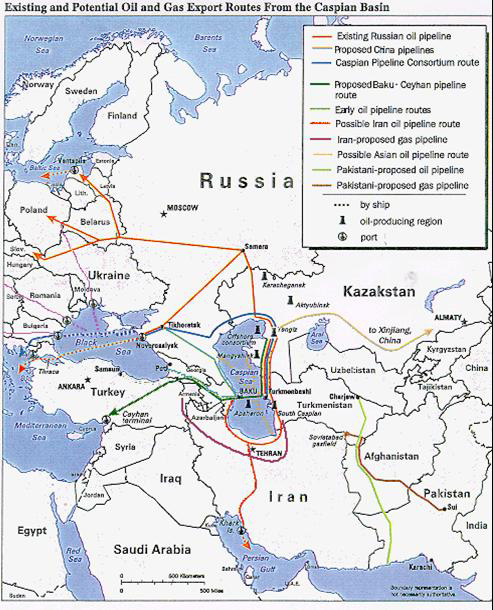

Oil

in the Caspian

At the

turn of the 20th century, the area around what is now Baku, Azerbaijan,

on the Absheron peninsula, was the world’s largest oil exporter. At the

turn of the 20th century, the area around what is now Baku, Azerbaijan,

on the Absheron peninsula, was the world’s largest oil exporter.

“Middle Eastern oil started in the Caspian,” says Igor Effimoff,

a Caspian expert who is now chief operating officer of Teton Petroleum Company

and who worked in the Caspian for Pennzoil Caspian Corp. and Larmag Energy

N.V.

Nonetheless, much of the oil frontier in the offshore of the Caspian region

remains underexplored and untapped. “For some years, the bulk of the

Caspian area lay relatively fallow because the Soviet Union had diverted

its resources to West Siberia, where huge reserves of oil and gas had been

discovered at shallow depths,” Effimoff says. “Not everything

has been found. There are many opportunities remaining in the Caspian.”

With the breakup of the Soviet Union, which had controlled most of the region,

five independent countries now border the Caspian Sea. All of them are interested

in developing their resources.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration

(EIA), the Caspian region’s proven, probable and possible oil reserves

(50 percent of probable) could be as high as 233 billion barrels. EIA says

the Caspian region — which it defines as the Caspian Sea, all of Azerbaijan,

Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, and the portions of Russia and Iran near the

Sea — is comparable to the North Sea in its hydrocarbon potential.

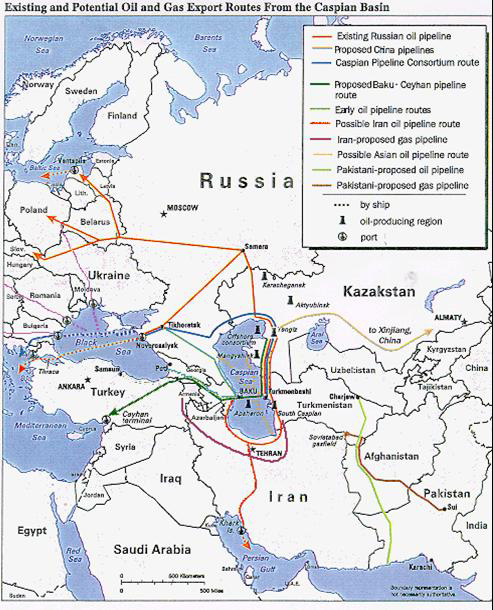

A map of the Caspian region and its

pipelines, supplied courtesy of Igor Effimoff, Teton Petroleum Co.

It is also possesses a huge natural gas resource. EIA estimates that the

region’s proven, probable and possible natural gas reserves are as

high as 293 trillion cubic feet. Azerbaijan is developing what could be

the largest new field discovered in the last 25 years, Shah Deniz.

The Caspian countries are accessing foreign investors and the latest technologies.

“What we’re talking about is not only technology in the marine

environment,” Effimoff says, “but also drilling deeper, more complicated

wells — onshore and offshore.”

At the same time, the United States is interested in developing oil resources

as alternatives to Middle East oil, and is putting the Caspian region in

the limelight.

Despite its fortuitous geology and access to new tools, complicated politics

will mean the region probably won’t begin to realize its full potential

for several years, says Andrew Neff, Eurasian Energy Analyst with EIA.

“The uncertainty surrounding the ownership of the Sea’s resources

… is probably the biggest obstacle to be overcome in order for the

Caspian to realize its full hydrocarbon potential,” Neff says. The

Soviet Union and Iran signed bilateral treaties to share the Caspian Sea;

but under new politics, debate continues among the five countries over how

to divide the Sea. Turkmenistan and, more strongly, Iran oppose a plan suggested

by Russia, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

The second obstacle, Neff adds, is a lack of export routes to transport

the oil and gas to consumers. “Investments in export infrastructure

will need to be made first, which brings us back to the lack of an agreement

on dividing the Sea.”

Also in recent years, some western companies drilling in the Caspian Sea

encountered dry holes or uncommercial quantities. Some of these failed sites

were near highly productive areas. “The disappointments have been mainly

driven by variations in geology that were not recognized before the wells

were drilled,” Effimoff says, adding that the region’s geology

is extremely complicated. One field can be completely different than a neighboring

field, he says. “To use a broad brush to talk about the Caspian is

dangerous.”

Effimoff adds that, just the same, optimism about the Caspian region remains

high because of the huge potential it promises. Already, consortia of international

energy companies have invested billions in four large projects for producing

three oil fields and the Shah Deniz gas field, along with pipelines to transport

the resources to market. These projects access portions of the Caspian Sea

where boundaries are not disputed.

Kristina Bartlett

Greg Peterson contributed to this report

Back to top |

| Oil

in Iraq

Of all the uncertainties in assessing world oil resources, one of the

greatest is the future of Iraq. The oil reserves in Iraq are among the

largest in the world, second only to Saudi Arabia. More than 100 billion

barrels of oil are known to exist within the country, and the U.S. Geological

Survey (USGS) estimates an additional 45 billion barrels remain to be

discovered. Yet war and sanctions have driven wild fluctuations in Iraq’s

oil production over the past 25 years, and the crystal ball for future

production is hazy at best.

“Iraq contains whole petroleum systems: world-class source rocks,

overlain by excellent reservoirs and terrific evaporite seals,” says

Thomas Ahlbrandt, a research geologist with USGS.

Many of the source rocks began forming in the Jurassic. Shallow seas periodically

inundated the northeastern section of the Arabian plate, where Iraq currently

sits. Those seas teemed with life, spurred by the warmth of the equatorial

latitudes. Thick layers of organic-rich shales and marine carbonates accumulated

in expansive basins and compressed into source rocks that remained little

disturbed for millions of years.

In the Tertiary, subduction of the Arabian plate beneath the Eurasian

plate drove the source rocks down into a “thermal generating window,”

Ahlbrandt says. High heat and pressure converted the shale and carbonate-rich

rocks into oil and gas. Much of the oil migrated up into anticlines sealed

by thick layers of salt and anhydrite left behind from the Jurassic seas

as they dried out.

Despite its immense reserves, Iraq’s oil production is low. In 2001,

Iraq produced 2.45 million barrels of oil per day, accounting for only

12 percent of the total oil produced in the Persian Gulf. The United States

produced more than three times that much, even though its reserves are

much smaller.

“They have the oil resources,” says Floyd Wiesepape, a petroleum

geologist with the Energy Information Administration, a part of the Department

of Energy. “It is a question of whether they have the wells or facilities

to increase production.”

Low production reflects years of sanctions and deteriorating drilling

infrastructure. On Aug. 6, 1990, four days after Iraq invaded Kuwait,

the United Nations banned all oil exports from the country. Oil production

dropped to 0.3 million barrels of oil per day, less than a tenth of what

it was before the Persian Gulf and Iran/Iraq wars began. For five years,

production barely exceeded what the country itself consumed. Wells and

supporting facilities fell into disrepair.

In 1996, Iraq began exporting oil again under the U.N. Oil-for-Food program.

The program set strict limits on the amount of oil that Iraq could export.

All revenue from the sales had to go toward food, medicine or other humanitarian

supplies for the people of Iraq. Oil production steadily increased for

the first few years of the program.

However, production has leveled off in the past 3 years, even though the

U.N. has removed the ceiling for the amount of oil that Iraq can produce

under the

Oil-for-Food program. Sanctions continue to discourage international investment

needed to boost production capacity. Russia, France and China have contracts

to develop oil fields in the region, but sanctions have slowed fulfillment

of those contracts.

Iraq claims production will increase quickly if the U.N. lifts sanctions,

Wiesepape says. “Iraq anticipates producing up to 3 million barrels

per day within a year or two, and up to 5 million a day within five years,

assuming they are not limited by demand, OPEC or sanctions.” Yet

the future of production is unclear, especially given the possibility

of a U.S.-led war in Iraq.

The United States does import some oil from Iraq, although the numbers

are low. In 2001, imports from Iraq accounted for only 5.5 percent of

the total U.S. imports. In contrast, imports from the Persian Gulf as

a whole added up to 20 percent - a significant contribution since the

United States relies on imports for more than half of its oil consumption

each year.

Greg Peterson

Back to top

|

In 2000,

the U.S. Geological Survey completed an assessment of the world’s conventional

petroleum resources, exclusive of the United States. This assessment is different

from those before it: Overall the 2000 assessment of potential petroleum resources

is higher than previous assessments, largely because it is the first USGS world

assessment to include field growth estimates.

In 2000,

the U.S. Geological Survey completed an assessment of the world’s conventional

petroleum resources, exclusive of the United States. This assessment is different

from those before it: Overall the 2000 assessment of potential petroleum resources

is higher than previous assessments, largely because it is the first USGS world

assessment to include field growth estimates. The assessment

suggests that some recent claims of an imminent oil shortage cannot be supported.

Furthermore, large volumes of natural gas can replace oil in most market sectors.

The rate of production of resources depends on many factors, including investments

in exploration and development, political conditions and the growth or decline

in demand from the global economy.

The assessment

suggests that some recent claims of an imminent oil shortage cannot be supported.

Furthermore, large volumes of natural gas can replace oil in most market sectors.

The rate of production of resources depends on many factors, including investments

in exploration and development, political conditions and the growth or decline

in demand from the global economy.

In an

abstract way, the amount of oil or gas in the world can be viewed as a pyramid

with a small amount of high quality resource that is cheap to extract, and with

increasing amounts of lower quality resource that cost more to extract. The

upper part of the pyramid is well defined, as these resources are mostly known

and are generally considered “conventional.” The lower part of the

pyramid is less well understood and the amount of petroleum in accumulations

that are now largely uneconomic — such as hydrates or basin-centered gas

— is highly speculative. An assessment draws a slice through the pyramid

defining the resource of oil or gas that is estimated to become economic within

the foreseeable future.

In an

abstract way, the amount of oil or gas in the world can be viewed as a pyramid

with a small amount of high quality resource that is cheap to extract, and with

increasing amounts of lower quality resource that cost more to extract. The

upper part of the pyramid is well defined, as these resources are mostly known

and are generally considered “conventional.” The lower part of the

pyramid is less well understood and the amount of petroleum in accumulations

that are now largely uneconomic — such as hydrates or basin-centered gas

— is highly speculative. An assessment draws a slice through the pyramid

defining the resource of oil or gas that is estimated to become economic within

the foreseeable future.  At the

turn of the 20th century, the area around what is now Baku, Azerbaijan,

on the Absheron peninsula, was the world’s largest oil exporter.

At the

turn of the 20th century, the area around what is now Baku, Azerbaijan,

on the Absheron peninsula, was the world’s largest oil exporter.