Geotimes

Energy & Resources

Coalbed Methane:

The Future of U.S. Natural Gas?

Lisa M. Pinsker

Rising demand

Hydraulic fracturing

What's in a name?

Web links

Rising demand

Methane is a buzz word these days both in the energy community and on the Hill,

where legislators are working to ensure the future security of energy resources

in the United States. National demand for natural gas is increasing, with the

resource now heating more than 50 percent of U.S. homes and fueling 95 percent

of new power plants.

Speaking to congressional

staffers at a briefing on Sept. 20, Rebecca Watson, assistant secretary for

land and minerals management at the Department of the Interior, said that coalbed

methane is the best source of energy to meet U.S. natural gas demand over the

next five to six years. That projection was echoed at an energy and environment

conference three days later held by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists

(AAPG), where earth scientists referred to the new era of the "methane

economy."

Speaking to congressional

staffers at a briefing on Sept. 20, Rebecca Watson, assistant secretary for

land and minerals management at the Department of the Interior, said that coalbed

methane is the best source of energy to meet U.S. natural gas demand over the

next five to six years. That projection was echoed at an energy and environment

conference three days later held by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists

(AAPG), where earth scientists referred to the new era of the "methane

economy."

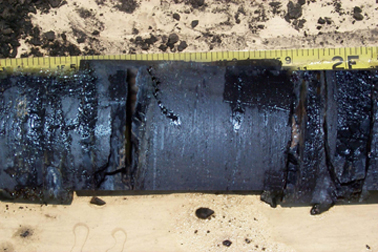

Hydraulic fracturing is necessary in order

to extract natural gas from coalbeds. Shown here are fractures and cleats (joint

systems along which the coal fractures) in a sample coal core. Photo courtesy

of USGS.

Coalbed methane is the natural gas that lies trapped in coal seams at shallow

depths. “It is different from other resources because it is both generated

and stored within the coalbeds themselves. It also is an attractive resource

because it occurs within coal, which is the most abundant fuel in the United

States,” said Patrick Leahy, associate director of geology for the U.S.

Geological Survey, at the congressional briefing. Coal acts like a sponge, storing

six times the volume of natural gas found in conventional reservoirs, Leahy

explained.

Over the past 20 years, coalbed methane production has increased steadily due

to its abundance and the relatively low cost of drilling at its shallow depths.

As of 2000, coalbed methane accounted for 7 percent of the total U.S. natural

gas production. Recent estimates put it at 9 percent of total U.S. natural gas

production.

The San Juan Basin

in Colorado is the world’s most prolific coalbed play, but the Powder River

Basin in Wyoming and Montana is the newest and most active coalbed play in the

United States, Leahy said. Conservative estimates put about 700 trillion cubic

feet of coalbed methane in place in the United States, of which 100 trillion

cubic feet are economically recoverable with existing technology. Annual U.S.

production now exceeds 1.25 trillion feet. According to the National Energy

Technology Laboratory’s Strategic Center for Natural Gas, the year 2001

saw 7,000 wells in the Powder River Basin producing 700 million cubic feet per

day.

The San Juan Basin

in Colorado is the world’s most prolific coalbed play, but the Powder River

Basin in Wyoming and Montana is the newest and most active coalbed play in the

United States, Leahy said. Conservative estimates put about 700 trillion cubic

feet of coalbed methane in place in the United States, of which 100 trillion

cubic feet are economically recoverable with existing technology. Annual U.S.

production now exceeds 1.25 trillion feet. According to the National Energy

Technology Laboratory’s Strategic Center for Natural Gas, the year 2001

saw 7,000 wells in the Powder River Basin producing 700 million cubic feet per

day.

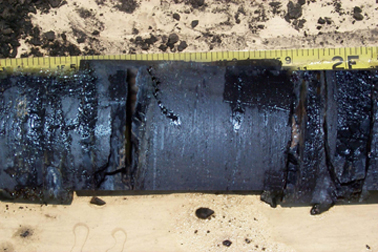

A coalbed methane wellhead dots the Powder

River Basin. Extending over southern Montana and northern Wyoming, the Powder

River Basin is the newest and most active U.S. coalbed play. Currently, the

Bureau of Land Management is reviewing all 5,100 gas leases in the Powder River

Basin. Photo courtesy of USGS.

Indeed, Peter Stark, of IHS Energy Group in Denver, told those attending the

AAPG conference that the Rocky Mountain states hold the most potential for future

gas supplies. However, he stresses that much of the federal land is out of bounds

for natural gas development, and that various regulations make an estimated

43 percent of Rocky Mountain gas unavailable for drilling.

Citing current political tensions between the United States and foreign interests,

AAPG speakers stressed the importance of developing domestic resources to ensure

energy security. For natural gas, the United States is relying more and more

on imports from outside the continent. However, Stark pointed out, North America

has ample resources, just not proper access to those resources, creating what

he called an urgent situation for domestic natural gas production.

With the rising natural gas demand, Stark said that the country will need to

reach a target of 162 trillion cubic feet of natural gas by the year 2020. To

do that, he says, the United States needs to develop 12 analogs to the Powder

River Basin. “Unless there is continuous and sustained drilling, coalbed

methane could peak as early as 2006.”

Back to top

Hydraulic

fracturing deemed safe

Hydraulic fracturing is a necessary step in extracting methane from coalbeds.

But since 1997, when an Alabama Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the state

should regulate the hydraulic fracturing of coalbeds as an underground injection,

citizens have expressed concerns that this extraction process may threaten the

underground water supply. As a result, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

recently completed the first ever comprehensive assessment of the potential risks

of hydraulic fracturing.

According to the EPA draft report released on Aug. 28, underground sources of

drinking water are safe from fracturing in coalbed methane wells; the effects

of hydraulic fracturing are small and do not merit further study. Despite the

fracturing of thousands of coalbed methane wells each year, the report found no

cases of drinking water wells contaminated by coalbed methane hydraulic fracturing.

To generate methane, coal must lie at least 200 feet below the surface and must

be below the water table because the water acts to trap the gas. Therefore, the

water must be released to allow the methane to migrate to the surface. In the

absence of natural fractures, methane extractors themselves must fracture the

coal seams — drilling a production well through the rock layers to intersect

the coal seam that contains the gas, and then pumping water down the borehole

to fracture the seam. A hydraulic fracture within the coal seam then acts as a

conduit that allows the coalbed methane to travel up the well to the surface.

“In a million wells that have been hydraulically fractured over the years,

not one has proven harmful to groundwater,” said Christina Hansen of the

Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission at a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) congressional

briefing in September. Hydraulic fracturing has been a common practice for 60

years, used on about 35,000 wells each year.

All that fracturing and extraction releases a lot of water — about 60 million

gallons per day — that needs to be disposed of somehow. “The water varies

in quantity and quality and from place to place,” says Patrick Leahy, associate

director of geology for USGS. In some places, the water is reusable for irrigation

and livestock and in other cases, it goes back into the ground. Evaporation ponds

are another common way to dispose of the water.

Although EPA, USGS and others have studied, and continue to study, the environmental

impacts of the various water disposal techniques, the water issues surrounding

coalbed methane continue to be contentious and stand at the heart of a legal and

regulatory battle in Wyoming and Montana.

Responding to public environmental concerns and a pending lawsuit, the Bureau

of Land Management decided in September to review all 5,100 gas leases in the

Powder River Basin — scrutinizing the adequacy of the environmental impact

statements for the region.

Back to top

What's in a name?

Not many people realize that coalbed methane is simply one form of natural gas.

Now that coalbed methane is becoming more important in discussions of U.S. energy

production, many people are calling for a name change to make the resource more

recognizable to the public.

During a September meeting in West Virginia of industry and government representatives

to discuss the growing demand for natural gas, West Virginia Gov. Bob Wise (D)

suggested changing the fuel source's name to something more familiar. "Because

this [fuel source] is now an important part of the total U.S. energy mix, the

industry needs to move away from using its confusing short-hand term, 'coalbed

methane.' The public understands the term 'natural gas' because they use it every

day. That is why we are calling this resource 'natural gas' and identifying its

source rock as coal seams," Wise said.

At a recent U.S. Geological Survey congressional briefing, Christine Hansen of

the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC) said IOGCC has adopted the

phrase "natural gas from coal seams" to describe coalbed methane.

IOGCC, the Interstate Mining Compact Commission, the U.S. Department of Energy

and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency all co-sponsored the West Virginia

conference. To learn more about the conference and name change, visit the IOGCC

Web site.

Back to top

Links:

EPA report on hydraulic

fracturing, now open for public comment

A Denver

Post article on a recent ruling by the Bureau of Land Management about some

leases in the Powder River Basin

Bureau of Land Management

Back to top

Speaking to congressional

staffers at a briefing on Sept. 20, Rebecca Watson, assistant secretary for

land and minerals management at the Department of the Interior, said that coalbed

methane is the best source of energy to meet U.S. natural gas demand over the

next five to six years. That projection was echoed at an energy and environment

conference three days later held by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists

(AAPG), where earth scientists referred to the new era of the "methane

economy."

Speaking to congressional

staffers at a briefing on Sept. 20, Rebecca Watson, assistant secretary for

land and minerals management at the Department of the Interior, said that coalbed

methane is the best source of energy to meet U.S. natural gas demand over the

next five to six years. That projection was echoed at an energy and environment

conference three days later held by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists

(AAPG), where earth scientists referred to the new era of the "methane

economy." The San Juan Basin

in Colorado is the world’s most prolific coalbed play, but the Powder River

Basin in Wyoming and Montana is the newest and most active coalbed play in the

United States, Leahy said. Conservative estimates put about 700 trillion cubic

feet of coalbed methane in place in the United States, of which 100 trillion

cubic feet are economically recoverable with existing technology. Annual U.S.

production now exceeds 1.25 trillion feet. According to the National Energy

Technology Laboratory’s Strategic Center for Natural Gas, the year 2001

saw 7,000 wells in the Powder River Basin producing 700 million cubic feet per

day.

The San Juan Basin

in Colorado is the world’s most prolific coalbed play, but the Powder River

Basin in Wyoming and Montana is the newest and most active coalbed play in the

United States, Leahy said. Conservative estimates put about 700 trillion cubic

feet of coalbed methane in place in the United States, of which 100 trillion

cubic feet are economically recoverable with existing technology. Annual U.S.

production now exceeds 1.25 trillion feet. According to the National Energy

Technology Laboratory’s Strategic Center for Natural Gas, the year 2001

saw 7,000 wells in the Powder River Basin producing 700 million cubic feet per

day.