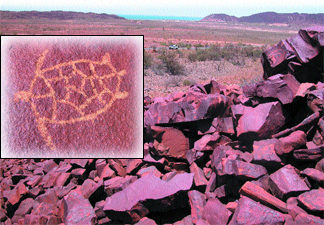

On a scattering

of remote islands called the Dampier Archipelago, located off the northwest

coast of Australia, people have been carving stories on rocks for thousands

of years. In some places, the rock carvings are so dense that they cover every

available surface of the deep red weathered rocks. Over the past 30 years, this

remote region, once home only to Aboriginal tribes and wallabies, has become

increasingly industrialized — leading to worries about possible acceleration

of weathering and deterioration of the rock art. With further development planned,

the government of Western Australia has commissioned a study of these relics

to determine what role industry might be playing in their deterioration.

On a scattering

of remote islands called the Dampier Archipelago, located off the northwest

coast of Australia, people have been carving stories on rocks for thousands

of years. In some places, the rock carvings are so dense that they cover every

available surface of the deep red weathered rocks. Over the past 30 years, this

remote region, once home only to Aboriginal tribes and wallabies, has become

increasingly industrialized — leading to worries about possible acceleration

of weathering and deterioration of the rock art. With further development planned,

the government of Western Australia has commissioned a study of these relics

to determine what role industry might be playing in their deterioration.In northwestern Australia, more than one million Aboriginal engravings pepper the landscape. Since the 1960s, development has been encroaching on the area, leading to worries about how emissions might be affecting weathering and deterioration rates of the rock art. Photos by Bill Carr.

“This is the largest petroglyph series in the world” and a very important area, says Robert Bednarik, an archaeologist who is president of the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO) and leader of a conservation movement to monitor and save the petroglyphs. No one knows exactly how many individual petroglyphs litter the surfaces of the 2.7-billion-year-old plutonic stones in Dampier, but estimates suggest more than one million. Bednarik has been working to preserve the site since 1969 when industry first moved in, he says.

Currently, the 22-kilometer-long Burrup Peninsula, which is located in the middle of the Dampier region, and is one of Australia’s busiest ports and hosts three large industrial facilities — a salt-processing plant, a liquid natural gas processing plant and an iron processing plant. The government of Western Australia has proposed adding six new industries to Burrup, thus bringing the debate over development versus cultural heritage preservation to a head. Bednarik and others urge that the industries instead move into a large alternative site nearby where there is little threat of endangering the petroglyphs.

“The government appreciates the cultural and heritage value of the rock art, while also recognizing [that] the Burrup industrial precinct is of vital economic importance to the local, state and national economies,” says Frank Murray, an environmental scientist at Murdoch University in Perth. So before deciding on a location, the government commissioned researchers from CSIRO (Australia’s national scientific research organization) and Murdoch University to monitor sites both near the industrial buildings and far across the Burrup Peninsula.

Work began this summer, and for the next four years, scientists will monitor atmospheric emissions and their effects on the rocks. At the end of the study period, they will report their findings to the government and recommend any future actions, says Murray, who is chair of the Burrup Rock Art Monitoring Management Committee, which oversees the studies. “These studies are to be the most thorough scientific research of impacts on rock art ever undertaken in Australia,” Murray says.

The CSIRO project is interdisciplinary and large in scope. Atmospheric scientists will measure ambient concentrations and deposition of pollutants from seven different sites. Microbiologists will examine the role of microbes in deteriorating the rock, and test whether increased levels of nitrogen or sulfur from emissions promote further microbial activity. And geochemists and archaeologists will assess the amount of weathering on the rocks by analyzing physical, mineralogical and chemical changes of the rocks, using optical and scanning electron microscopes. They will also use a mineral mapping tool to record subtle color and mineral spectral changes in the surface minerals over time between the engravings and the adjacent undisturbed rock surfaces.

Such techniques have in part been used worldwide, including in the American Southwest, to monitor changes to rock art, but this is new for Australia, Bednarik says. The CSIRO project is a “step in the right direction in the sense that it will provide good quantitative data on real pollution and pollutant precipitation,” Bednarik says. But, he says, the study lacks depth in researching the geochemistry of the rocks and the deterioration processes.

Still, as acid rain and emissions threaten sites worldwide, the effect of modern society on rock art is an important topic to study and is definitely under-researched, says Ben Swartz, an archaeologist at Ball State University in Indiana who is active in IFRAO. But even more than conservation, he says, the most important thing is to “record what’s there, before it’s gone.”

Megan Sever

Back to top