In a paper published

in the Aug. 1 Nature, Simon Stewart of British Petroleum (BP) and Philip

Allen of Production Geoscience Ltd. describe a 20-kilometer-diameter structure

in the North Sea that bears striking similarity to impact craters on Jupiter’s

icy moons Callisto and Europa. Yet, while it resembles craters found elsewhere

in the solar system, the newly discovered “Silverpit” crater is only

one-tenth to one-hundredth the diameter. Equally intriguing to geologists, Silverpit’s

concentric ring structure is unlike any other impact crater found on Earth.

In a paper published

in the Aug. 1 Nature, Simon Stewart of British Petroleum (BP) and Philip

Allen of Production Geoscience Ltd. describe a 20-kilometer-diameter structure

in the North Sea that bears striking similarity to impact craters on Jupiter’s

icy moons Callisto and Europa. Yet, while it resembles craters found elsewhere

in the solar system, the newly discovered “Silverpit” crater is only

one-tenth to one-hundredth the diameter. Equally intriguing to geologists, Silverpit’s

concentric ring structure is unlike any other impact crater found on Earth.

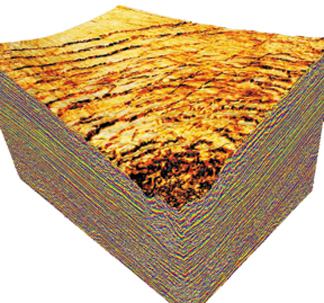

Seismic impression of the impact structure. 3-D Image Processing and Analysis by ffA

Named after an overlying channel, the Silverpit crater lies buried hundreds of meters beneath the sea floor within Cretaceous chalks and Jurassic shales. Stewart and Allen suggest that the crater’s structure reflects the material it hit: interbedded chalks and clays that lay beneath 50 to 300 meters of sea water. These sedimentary features yield a decrease in sediment strength with depth, creating so-called detachment layers that earlier models have linked to multi-ringed craters.

“Learning to detect the remains of marine impact structures is very important because two-thirds of all impacting objects hit the oceans,” says David Kring of the University of Arizona, a leading expert on impact structures. Yet, most of the impact sites that researchers discover are on land, skewing the global inventory, he adds. “This prevents us from properly evaluating the consequences of past impact events and also hinders our evaluation of future impact hazards.”

The crater only recently came to light when Allen was poring over high-resolution, 3-D seismic reflection data in search of gas reservoirs. Having worked in geophysics for three decades, Allen has seen a wide variety of geologic features, yet the Silverpit concentric-ring structure was initially puzzling. In fact, Allen had posted a printout of the seismic data on his office wall, along with a note asking: “Has anybody seen anything like this?”

“He wasn’t sure what it was,” Stewart remembers. “But I coincidentally saw his map several months later on an unrelated visit.” Stewart, a structural geologist with experience studying craters and other circular features, realized that the structure might be an impact crater.

The seismic data, now owned by BP, were actually collected a decade ago by Western Geophysical for Arco International Oil and Gas Company, which has since merged with BP. According to Stewart and Allen, the seismic data may be the first high-resolution map in three dimensions of the internal structure of a concentric, multi-ringed impact structure.

However, because of Silverpit’s small size compared to other multi-ring craters, and because of its earthly provenance, other scientists want to see more data before drawing final conclusions.

In search of the

outcrop-scale features necessary to confirm that Silverpit is in fact an impact

crater, Stewart and Allen inspected data from two drill cores taken from within

the structure. While they did not find irregularities in the core data pointing

to an impact origin, they also failed to find evidence for either a volcanic

origin or a salt diapir.

In search of the

outcrop-scale features necessary to confirm that Silverpit is in fact an impact

crater, Stewart and Allen inspected data from two drill cores taken from within

the structure. While they did not find irregularities in the core data pointing

to an impact origin, they also failed to find evidence for either a volcanic

origin or a salt diapir. Structural geologist Dr Simon Stewart (left) of BP Upstream Technology discusses the Silverpit crater with geophysicist Phil Allen of Production Geoscience Ltd. Courtesy Newsline Scotland

“Shock-metamorphic features are the principal diagnostic feature of confirmed impact craters, although these may be difficult to find in a marine impact structure involving chalk,” Kring says. “The lack of any root stocks beneath the structure is promising,” he adds, “suggesting the structure was not created by material being fed from below, as in a rising salt dome or magmamatic intrusion.”

Evidence from drill cores of the Eltanin site in the Southeast Pacific reveals an impact occurred in the ocean southwest of Chile two million years ago, even though there is not yet evidence for a crater. If the Eltanin site is a good guide, Kring says, “it may be possible to find surviving relics of an impacting object in the form of fragmented meteoritic debris around the Silverpit structure and possibly some glassy material representing impact-melted chalk.”

Stewart and Allen are continuing their study in an effort to find such conclusive evidence. “In the near term,” Stewart says, “we are doing detailed examination of the available drill cuttings from nearby wells to see if we can find either volcanic or impact related fragments.”

The researchers say the impact research community has responded enthusiastically to their study. Stewart and Allen have received numerous calls from geoscientists about other unusual, “ringed” structures, and research teams are conducting modeling studies to determine what impact scenarios can create the complex, concentric ring patterns.

However, the extent of the project is growing beyond the petroleum geologists’ original task.

“There is clearly scope for more detailed future research that we may have to leave for an academic institution to pick up,” Stewart says. “This is not really our day job.” Although, he adds, “I hope the Silverpit story is an example of how hydrocarbon industry data can be reused to reveal phenomena that are of broader interest.”

Josh Chamot

Geotimes contributing writer