Geotimes

Feature

Water, Agriculture

and Land Cover: Lessons for the Postwar Era

Mohamed Sultan, Richard Becker, Ahmad Al-Dousari, Abdul Nabi

Al-Ghadban and Elizabeth Bufano

Countries of the Middle East have many reasons to envy their neighbor Iraq:

not only does Iraq have the second-largest proven oil reserves (after Saudi

Arabia), but it has more renewable water resources than any other Middle Eastern

nation. Thousands of years ago, the plentiful water resources of the Tigris

and Euphrates rivers promoted widespread and organized cultivation along their

riverbanks, which led to the development of the world’s earliest civilization

in the river valleys — the Mesopotamian civilization. Since then, agriculture

has been the primary economic activity of the Iraqis. But the past century has

brought considerable change.

A

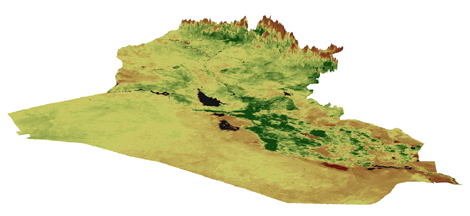

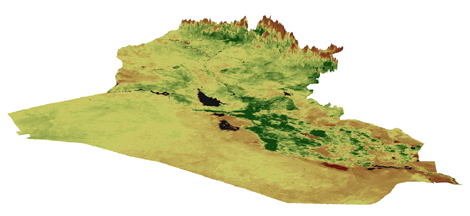

3-D representation for the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) draped

over vertically-exaggerated topographic data (1-kilometer digital terrain elevation

data) for Iraq. The NDVI image was derived from Advanced Very High Resolution

Radiometer data acquired on Jan. 21, 1996. The image shows the relief of Iraq

and displays in shades of green the distribution of vegetated areas and in shades

of yellow the distribution of deserts. Snow appears in shades of brown. Image

courtesy of Mohamed Sultan.

A

3-D representation for the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) draped

over vertically-exaggerated topographic data (1-kilometer digital terrain elevation

data) for Iraq. The NDVI image was derived from Advanced Very High Resolution

Radiometer data acquired on Jan. 21, 1996. The image shows the relief of Iraq

and displays in shades of green the distribution of vegetated areas and in shades

of yellow the distribution of deserts. Snow appears in shades of brown. Image

courtesy of Mohamed Sultan.

With the discovery of oil in Iraq, investment there has massively shifted from

agriculture to the oil industry; agriculture now accounts for only 8 percent

of Iraq’s total gross domestic product. This shift in investment, coupled

with the implementation of inefficient centrally controlled agricultural policies,

has adversely affected agricultural productivity and contributed to land degradation.

Mounting pressures to produce more food for the region’s growing population

has led to the adoption of aggressive water management programs in the region,

bringing drastic modification to the Iraqi landscape and habitat, particularly

the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys. With the current political situation,

Iraq and its neighbors now have the opportunity to work together toward the

implementation of environmentally sound policies when it comes to management

of the water, land, agricultural and ecological resources of the region.

|

Vegetation and Rainfall

over Iraq

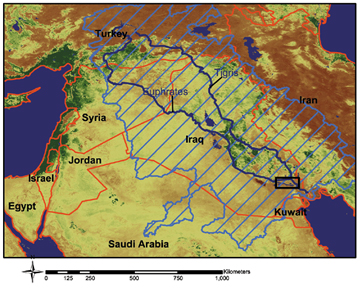

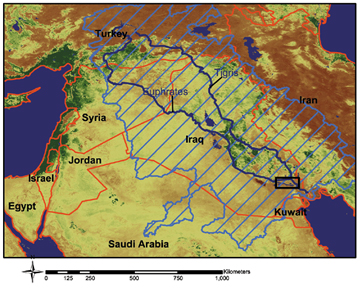

In this regional view, processed color composite image of weather satellite

data (AVHRR) acquired in January 1996 give a different perspective of

vegetation over Iraq and surrounding countries. Shades of green indicate

areas covered by vegetation; the areas in shades of yellow are deserts;

and shades of brown show highlands covered by snow. The figure also shows

the extent of the watershed that feeds these rivers (hachured in blue).

Image courtesy of Mohamed Sultan.

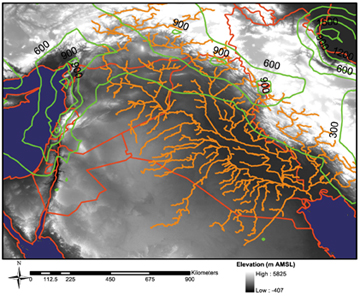

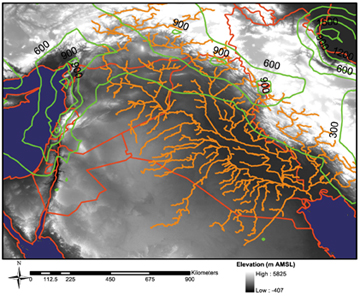

Shown here is the distribution of

rainfall over the highlands within the watershed. Average annual rainfall

is shown by green contours; elevation is shown in shades of gray; and

the watershed is defined by the stream network, which is shown in shades

of orange. Image courtesy of Mohamed Sultan.

|

According to the World Water Development Report, total renewable water resources

available per capita per year in Iraq amount to 3,287 cubic meters. This does

not put Iraq in the league of the water-rich countries in North America and

Western Europe that receive 10,000 cubic meters or more of water per capita

per year. However, Iraq’s renewable water resources are abundant when compared

to other neighboring countries, including the Gulf states, Israel, Jordan and

the Palestinian Territory; most of these regions fall short of 500 cubic meters

of water per capita per year.

Iraq’s relatively plentiful water resources have distinguished its landscape

from its more arid desert surroundings, making Iraq a lush forest when compared

with many of its neighbors. The precipitation over the watershed that feeds

the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers largely falls over the mountainous areas

in the northern, northeastern and eastern highlands in Turkey, Iraq and Iran.

The headwater catchment generating the Tigris and Euphrates is extremely high

in elevation, with the source area for the Euphrates near Lake Van in Turkey

reaching elevations of 4,500 meters (14,674 feet). The sources of the Euphrates

originate almost exclusively in the highlands of Turkey. The sources for the

Tigris, however, are distributed throughout Turkey, Iran and Iraq. Downstream,

the picture is different; the land is extremely flat, falling in elevation only

a few centimeters per kilometer, which gives rise to meandering channels and

eventually to marshlands.

The landscape of Iraq has endured many changes over the past few decades. The

areas occupied by the marshlands have been affected most, with the largest changes

occurring in the 1990s. In general, the marshlands have been on the decline,

in some cases replaced by arable lands; in others, however, they have unfortunately

been transformed into desiccated salinized land. Until the 1970s, the Mesopotamian

marshlands extended over an area of 15,000 to 20,000 square kilometers in central

and southern Iraq. Today, the Central and Al Hammar marshlands have almost entirely

disappeared — vegetated land cover has been transformed into barren land

and salt crusts. Only one-third of the Hawr Al Hawizeh marshlands remain (see

Geotimes, this issue).

These observed land-cover and land-use changes over the Mesopotamian marshes

mostly reflect the impacts of large engineering projects on the hydrology of

the Tigris-Euphrates basin. Iraq and its upstream neighboring countries have

implemented these projects. Iraq had plans to develop drainage systems that

would discharge saline runoff from irrigated agricultural lands to the sea —

waters that would drain into the marshes and increased their salinity. However,

that project somehow evolved into efforts aimed at developing agricultural lands

at the expense of the marshlands.

Although the

construction of these projects began in the 1970s, Iraq didn’t embark on

its marshland-draining project until the end of the 1991 Gulf War. There have

been speculations about the true motivation behind the implementation of the

project because the drained marshlands remain largely uncultivated. Some have

suggested that Saddam Hussein developed the project to punish the population

in the south that started an uprising against his regime in 1991. The degradation

of the marshlands has led to the migration of an estimated half-million Marsh

Arabs and has devastated the biodiversity and wildlife there as well. Any future

water-management schemes should have a strong component dedicated to the partial

restoration of the marshlands.

Although the

construction of these projects began in the 1970s, Iraq didn’t embark on

its marshland-draining project until the end of the 1991 Gulf War. There have

been speculations about the true motivation behind the implementation of the

project because the drained marshlands remain largely uncultivated. Some have

suggested that Saddam Hussein developed the project to punish the population

in the south that started an uprising against his regime in 1991. The degradation

of the marshlands has led to the migration of an estimated half-million Marsh

Arabs and has devastated the biodiversity and wildlife there as well. Any future

water-management schemes should have a strong component dedicated to the partial

restoration of the marshlands.

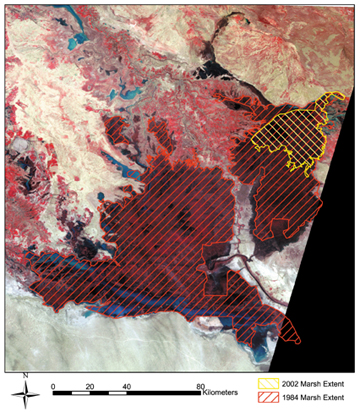

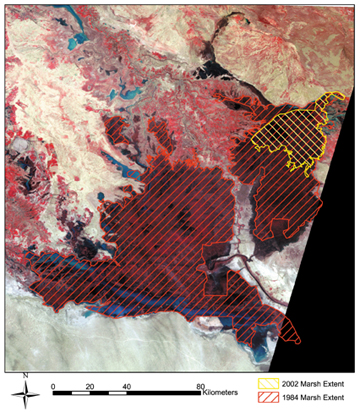

The decline in the area occupied by the

marshlands throughout the past three decades is apparent in these images. Marshlands

appear as dark areas on the 1977 Multispectral Scanner (MSS) satellite image.

The aerial extent of the marshes in 1984 and 2002 were extracted from temporal

satellite, Landsat, data and were plotted for comparison on the 1977 image.

Image courtesy of Mohamed Sultan.

In addition to the drainage systems, dams were also responsible for the devastation

of the marshlands. Countries sharing the Tigris-Euphrates watershed, namely

Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria, have constructed more than 30 major dams to store

water and to tame the flow of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Around the same

time the Iraqis were embarking on the construction of the marsh-drainage canal

system, damming projects were accelerating in the region. For example, in 1989,

Turkey launched an integrated regional development project that would develop

a series of dams upstream on both the Euphrates and the Tigris, potentially

reducing the flow of the Euphrates in Iraq by as much as 80 percent and in Syria

by 40 percent. Both Syria and Iraq threatened to go to war over their access

to Euphrates waters. To date, a regional water-sharing agreement has not been

reached, and the need for reaching such an agreement is heightening, as water

shortages likely will become more acute with time.

The political conflicts and disputes, escalating wars, and ever-shifting alliances

have derailed previous attempts to reach equitable reconciliation schemes. Only

limited guidelines in international law exist today to regulate the trans-boundary

rivers and to define the rights and obligations of riparian states. We hope

that the postwar conditions and new political systems in place can provide the

atmosphere of stability that is required to conduct the lengthy and difficult

negotiations that are needed to reach such agreements. With more than 90 percent

of Iraq’s available water resources used for agricultural purposes, such

water-sharing agreements would affect the agricultural sector the most.

The vegetated areas are largely concentrated in central Iraq, where the marshlands

are located, and in the northeast as well. Currently, a large portion of the

vegetated lands are farmlands, which cover approximately one-fifth of Iraq’s

territory; they are sub-equally divided in aerial extent between rain-fed farmlands

in the northeast and the valleys of the Euphrates and the Tigris. Under the

centrally controlled agricultural system that Saddam Hussein had in place, the

government controlled the prices of agricultural products, and farmers had little

incentive to increase productivity. They also did not have adequate access to

modern resources, such as machinery and irrigation equipment, fertilizers, pesticides,

and appropriate (for example, saline-resistant) feedstock.

Currently, excessive use of water for irrigation is a common practice because

water use is not modernized; such practices in warm countries such as Iraq promote

salinization of soils, a problem acknowledged, but not addressed on a regional

scale, by the previous administration. Regardless of the outcome of any negotiations

with its neighbors pertaining to water allocations, Iraq should exert efforts

and resources to evaluate and develop alternative water resources. Examples

of these alternative resources include groundwater and nonconventional water

resources (for example, recycling wastewater and desalinizing brackish waters).

Iraq should also develop nationwide programs to modernize water usage perhaps

by adopting water pricing and by implementing modern and efficient irrigation

systems.

In this part of the world, political realities have cast deep shadows over the

environmental arena. The approval of a country’s political system in the

Middle East is generally needed for large engineering and environmental projects

to proceed. Currently, the identification of these projects and the timing of

their implementation are not driven by balanced social, economic, environmental

and scientific factors, but rather by decisions made on the highest political

levels with or without the support of the scientific community. Iraq has not

been any different. As the country embarks on a new era of political freedom,

it hopefully can provide an example to neighboring nations of how to replace

the status quo with progressive and dynamic water-management schemes —

implemented on a solid scientific, economic, societal and environmental basis.

Sultan is a professor in the

Department of Geology at the University at Buffalo (UB), SUNY, and he is the director

of the Earth Sciences Remote Sensing (ESRS) facility. Becker is a senior research

scientist at UB’s ESRS. Al-Dousari is a senior research scientist at Kuwait

Institute for Scientific Research. Al-Ghadban is the manager of Environmental

Sciences Department at the Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research. Bufano is

a research scientist at ESRS.

Links

"Iraq's

Marshes Renewed," Geotimes, October 2003

Back to top

A

3-D representation for the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) draped

over vertically-exaggerated topographic data (1-kilometer digital terrain elevation

data) for Iraq. The NDVI image was derived from Advanced Very High Resolution

Radiometer data acquired on Jan. 21, 1996. The image shows the relief of Iraq

and displays in shades of green the distribution of vegetated areas and in shades

of yellow the distribution of deserts. Snow appears in shades of brown. Image

courtesy of Mohamed Sultan.

A

3-D representation for the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) draped

over vertically-exaggerated topographic data (1-kilometer digital terrain elevation

data) for Iraq. The NDVI image was derived from Advanced Very High Resolution

Radiometer data acquired on Jan. 21, 1996. The image shows the relief of Iraq

and displays in shades of green the distribution of vegetated areas and in shades

of yellow the distribution of deserts. Snow appears in shades of brown. Image

courtesy of Mohamed Sultan.

Although the

construction of these projects began in the 1970s, Iraq didn’t embark on

its marshland-draining project until the end of the 1991 Gulf War. There have

been speculations about the true motivation behind the implementation of the

project because the drained marshlands remain largely uncultivated. Some have

suggested that Saddam Hussein developed the project to punish the population

in the south that started an uprising against his regime in 1991. The degradation

of the marshlands has led to the migration of an estimated half-million Marsh

Arabs and has devastated the biodiversity and wildlife there as well. Any future

water-management schemes should have a strong component dedicated to the partial

restoration of the marshlands.

Although the

construction of these projects began in the 1970s, Iraq didn’t embark on

its marshland-draining project until the end of the 1991 Gulf War. There have

been speculations about the true motivation behind the implementation of the

project because the drained marshlands remain largely uncultivated. Some have

suggested that Saddam Hussein developed the project to punish the population

in the south that started an uprising against his regime in 1991. The degradation

of the marshlands has led to the migration of an estimated half-million Marsh

Arabs and has devastated the biodiversity and wildlife there as well. Any future

water-management schemes should have a strong component dedicated to the partial

restoration of the marshlands.