“Mega-tsunami

threatens to devastate U.S. coastline.” “Scientists warn of massive

tidal wave from volcano.” “Active volcano to destroy New York City

with 150-foot waves.” In mid-August, headlines like these swept through

the news wires. If the warnings sound familiar, it may be because the same set

of headlines circulated in 2000, 2001 and 2002. Fortunately, mega-tsunamis are

not nearly as frequent as the news stories, and the likelihood of an event is

relatively low. Continued debate among scientists, however, keeps the stories

in the news and heightens the perceived threat.

“Mega-tsunami

threatens to devastate U.S. coastline.” “Scientists warn of massive

tidal wave from volcano.” “Active volcano to destroy New York City

with 150-foot waves.” In mid-August, headlines like these swept through

the news wires. If the warnings sound familiar, it may be because the same set

of headlines circulated in 2000, 2001 and 2002. Fortunately, mega-tsunamis are

not nearly as frequent as the news stories, and the likelihood of an event is

relatively low. Continued debate among scientists, however, keeps the stories

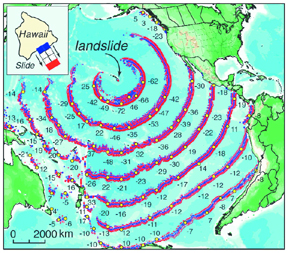

in the news and heightens the perceived threat.This computer model presents the worst-case scenario for a collapse of Kilauea’s southeast flank, resulting in a 30-meter-high wave striking the U.S. West Coast. Tsunamis are marked at two-hour intervals in red (wave crest) and blue (trough), with numbers corresponding to wave height. Image courtesy of Steve Ward.

The epicenter of the latest alert was a news conference held by the Benfield Hazard Research Center at University College London. The center’s director, Bill McGuire, told a group of reporters that a volcano on the island of La Palma in the Canary Islands off the West Coast of Africa will one day collapse, triggering tsunamis that could hit the U.S. coastline in a matter of hours. “This is a real threat,” McGuire says. “It seems unusual, but it is pretty normal for a steep-sided oceanic volcano.”

The scenario plays out something like this: During a major eruption, a volcano experiences catastrophic flank failure. A large section of the volcano crashes into the sea and sets off an enormous tsunami that radiates out in every direction. “Mount St. Helens is a good terrestrial example, but there is no analogous example in a volcanic island,” says Russell Wynn, a researcher at Southampton Oceanography Center, who has questioned the seriousness of the La Palma scenario.

Wynn has studied landslide deposits in the waters around the Canary Islands and says that volcanic collapses occur roughly once every 100,000 years, with the last one about 15,000 years ago. “In that time, there have been hundreds of thousands of eruptions without flank failure,” he says. “Yes, there is some instability, but it is a rather large hop and a jump to suggesting huge tsunamis are imminent.” Wynn’s research also indicates that future collapses will occur piecemeal. “If you throw a brick into the water, it is going to make a big splash, but if you break that brick up into smaller pieces, there will be more moderate-sized waves,” he says.

McGuire, however, says that Wynn is relying too heavily on past events. Headline-grabbing research in 2001 by McGuire’s colleague, Simon Day, and by Steve Ward at the University of California, Santa Cruz, examined a part of the volcano that detached during an eruption in 1949. “Right now, it is moving as a coherent block,” McGuire says. “We are convinced that the slide will take place catastrophically. We’re not waiting for the collapse to occur; the collapse started in 1949. We’re waiting for the coup de grace.”

Ward, who modeled the tsunami in his 2001 paper, says that some cautionary steps are needed. “I think it would be worthwhile to invest a few ten thousand dollars per year to monitor the island,” he says. “This type of landslide would likely take months or years of pre-eruption activity,” so it would be easy to ramp up observations as an eruption neared, he says.

Ward made headlines again in 2002, when he published a comment in Nature outlining what would happen if a chunk of Kilauea, in the Hawaiian Islands, fell into the sea. An earlier report had noted a block of the island slipped several centimeters seaward. What Ward modeled “is the absolute worst-case scenario,” says Asta Miklius, a geophysicist at the Hawaii Volcano Observatory. “In Hawaii there is less than one large landslide per 100,000 years,” she says. “We don’t fully understand how these extremely large landslides form, so discussion about them generating mega-tsunamis is highly speculative.” Miklius says the threat of earthquake-induced tsunamis is much greater than tsunamis caused by submarine landslides. In 1975, for example, a magnitude-7.2 earthquake off the coast of Hawaii caused a 26-foot-high tsunami that killed two campers at a local beach.

Ward says it is “fair” to call the Kilauea example a worst-case scenario, which includes 100-foot waves beaching on California. But he adds that “there are a range of scenarios you can examine, including the worst-case.” On average, he says, these events happen globally every 10,000 years. “In geologic time that’s a blink of the eye, but for an individual insuring your car or house, there’s not much to worry about.”