Voter opinion polls leading

up to the November election consistently cite education as one of the most important

presidential issues. The highly controversial No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB)

is at the center of the election-year debate on education reform. The law is

designed to hold public schools accountable for closing the achievement gap

between students with different backgrounds. Now, almost three years since President

Bush signed NCLB into law, science teachers are starting to see the effects

in the classroom.

Voter opinion polls leading

up to the November election consistently cite education as one of the most important

presidential issues. The highly controversial No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB)

is at the center of the election-year debate on education reform. The law is

designed to hold public schools accountable for closing the achievement gap

between students with different backgrounds. Now, almost three years since President

Bush signed NCLB into law, science teachers are starting to see the effects

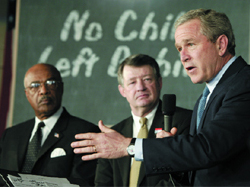

in the classroom.President Bush and Education Secretary Rod Paige (at far left) celebrate the second anniversary of the No Child Left Behind Act at West View Elementary School in Knoxville, Tenn., where students have made significant improvements in reading and math test scores. Image courtesy the White House.

At the heart of NCLB are several key measures, including annual student testing. Currently, states must test students in grades three through eight in reading and math. The results of the tests are available to parents, teachers and school officials who can assess their school’s strengths and weaknesses. Carolyn Snowbarger, the director of the Teacher to Teacher Initiative at the Department of Education, says that “teachers will be able to look at the scores of their students and tailor their teaching practices to individual students’ needs.”

Once students are tested, their math and English (and eventually science) scores are separated by subgroup (low-income, minority, limited English and disabled). If any one subgroup (which can be further divided by individual states into multiple categories) does not meet the standards, the federal government designates the school as in need of improvement. “For the first time Congress is holding schools accountable for all groups of students, not just the average,” says Kevin Carey, a senior policy analyst at the Education Trust, a nonprofit group that advocates for closing achievement gaps. Students at struggling schools can request extra tutoring or school transfers. If a school continually fails to make improvements, the federal government will take more drastic steps such as school takeovers.

Annette Sieve, an eighth-grade science teacher at Francis Howell Middle School in St. Charles, Mo., says she supports the goals of NCLB, but does not know if the new testing will have a noticeable effect in the classroom. “We are already doing all we can to make sure every student succeeds,” Sieve says. Schools and teachers take many steps to ensure that no student falls behind, she says. EllaJay Parfitt, a seventh- and eighth-grade science teacher at Southeast Middle School in Baltimore, Md., agrees, saying that NCLB just puts in writing what teachers have been doing all along.

For elementary school teachers, however, who teach all subjects including science, the current focus on reading and math may detract from science education. “Because of the upcoming tests, elementary teachers are reducing science in the curriculum and in some cases removing it completely,” says Jodi Peterson, the director of legislative affairs at the National Science Teachers Association. Carol Bauer, a fourth-grade teacher at Grafton Bethel Elementary in York County, Va., says that she feels the pressure from NCLB. “Knowing that the kids are going to be tested, we have to focus on that material,” Bauer says. “There are so many wonderful and cool science experiments out there and when you have to spend so much time preparing for tests, you don’t always have time for them.”

In some cases, however, shifting the focus to math and reading “may be appropriate,” Carey says. Indeed, Harrison Collier, a teacher and math coach at Washington Park Elementary School in Cincinnati, Ohio, says that science is fundamentally about reading and math skills and “if you shore those areas up first, then the other areas will fall into place.” He adds that teaching reading, math and science are not mutually exclusive and in the ideal scenario, teachers integrate science into the reading and math curriculum.

Such integration has been inevitable with NCLB, Parfitt says. “Teachers have become very good at finding creative ways to incorporate science into their teaching.” For example, second-graders study the life cycle of butterflies in reading class and then “confirm their observations with the science literature and incorporate that into their writing,” says Michael Szesze, the program supervisor for science at Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland. NCLB requires that states begin testing for science by the 2007-2008 school year. Parfitt says she hopes the new science testing will “turn around” the declining emphasis on science education.

In addition to testing students, NCLB requires all teachers to be “highly qualified” by 2006. Highly qualified teachers must possess a bachelor’s degree, have state certification and demonstrate knowledge in the subjects they teach. Having highly qualified teachers in the classroom is one of the most significant factors in improving student achievement, Snowbarger says.

For states, teacher qualification is also one of the most significant challenges. Reports in 2003 and 2004 by the Education Commission of the States, a Denver-based group that advises state leaders, show that although the numbers are improving, no states are on track to meet teacher quality standards by 2006. In response, the Department of Education extended the deadline for rural teachers, who often teach more than one subject, to become highly qualified in subjects they teach. But that may not be enough.

Daniel Kaufman, a spokesman for the National Education Association, a teachers union with over 2.7 million members, says that other groups of teachers, such as urban and special education teachers, face similar problems but do not receive any relief. “There’s already a shortage of science teachers,” he says. “Some additional flexibility is needed.”

“Many teachers have approached us and said they are afraid they won’t meet the new standards,” Peterson says. “One of the areas of greatest concern is middle school teachers, many of which are teaching with elementary school credentials.” Parfitt says that “some [teachers] have to rely on what they themselves took in high school.” Middle school teachers seeking to become highly qualified must compete with other teachers for limited professional development funds.

Limited funding is one of the largest impediments to teacher training, Peterson says. Before NCLB, the federal government allocated specific funds for science and math teacher development. Under the new law, that money is combined with other funds and “is at the states’ and districts’ discretion as to how to be spent,” Peterson says. Most states try to support teacher development programs in science, but “in some instances, that money is being spent on reading programs, since that is what schools are going to be tested on,” she says. “Teachers used to depend on that money.”

For example, Maryland, which was already struggling with its budget, decided to reduce some science teacher training programs, Parfitt says. “A lot of professional development programs for science in Maryland did not get funded or were only partially funded.” The issue of funding is receiving a lot of attention on the national stage. Many Democratic politicians like Sen. Ted Kennedy (Mass.) and Sen. Christopher Dodd (Conn.), who fervently supported NCLB at its signing, are now critical of the Bush administration’s level of funding. On the campaign trail, presidential hopeful Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.) routinely accuses Bush of denying public schools the money they need to succeed. The White House counters that overall funding for public schools has increased by almost 50 percent since Bush took office.

Kaufman says that the extra money the schools receive is quickly used up to meet the requirements of NCLB. Bush’s budget requests have also been well below what Congress authorized, Kaufman says. The Kerry-Edwards campaign has pledged to “ensure that NCLB works for schools, states and teachers,” but it is unclear exactly what changes they would make. “It is anybody’s guess what is going to happen after the election,” Peterson says.

Most teachers realize that NCLB is here to stay and are taking the bad with the good. “Teachers like the spirit of the law,” Szesze says, but “find it challenging to meet its demands.” Collier says that “[NCLB] has caused a lot of stress for teachers,” but it has also “heightened the awareness of the achievement gap.” At a fundamental level, Collier adds, “NCLB has empowered children to become the stewards of their own education.”

Or, as the great American writer, Mark Twain, once said, “I have never let my schooling interfere with my education.”

Back to top