Geotimes

Untitled Document

In Memoriam:

Philip Hauge Abelson

Thomas Gold

Philip Hauge Abelson

Brooks Hanson

Philip Hauge Abelson passed away on

Aug. 1 at the age of 91. Although some of his early work in physics is most

often recognized, when forced to choose, he considered himself a geologist.

From the age of 30, Abelson never was satisfied working one job in one field.

He was an interdisciplinary researcher, director, president, editor and writer

— and avid walker and gardener just to fill out the day.

Philip Hauge Abelson passed away on

Aug. 1 at the age of 91. Although some of his early work in physics is most

often recognized, when forced to choose, he considered himself a geologist.

From the age of 30, Abelson never was satisfied working one job in one field.

He was an interdisciplinary researcher, director, president, editor and writer

— and avid walker and gardener just to fill out the day.

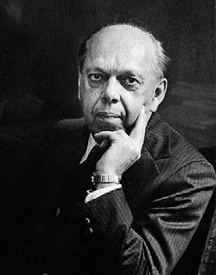

Geologist Philip Hauge Abelson died on

Aug. 1 at the age of 91. Image courtesy of Yoichi Okamoto, courtesy of the Carnegie

Institution of Washington Archives.

An eclectic scientist and passionate scientific optimist, Abelson was concerned

and involved with encouraging scientists and interdisciplinary science and with

making science work for society. He fostered these interests and goals while

serving as director of the Naval Research Laboratory in Philadelphia in 1944,

the Geophysical Laboratory from 1953 to 1971 and the Carnegie Institution of

Washington from 1971 until 1978, as well as president of the American Geophysical

Union. From 1962 until 1983, he also was the editor of Science. He continued

to serve on the Science editorial board, and was an adviser to other boards

interfacing between science and society.

After earning degrees at Washington State University in chemistry and physics,

Abelson conducted graduate work in nuclear physics at the University of California,

Berkeley. Continuing a collaboration that began there, Abelson and Edwin McMillan

created the first artificial element, neptunium, and had tantalizing hints of

plutonium. Working independently, he developed an approach that was used in

part to produce the material for the first atomic bomb. He then helped conceive

and initiate the nuclear submarine program.

His time at the Geophysical Laboratory, first in 1939 and then again in 1946,

fostered his work on biology and geology, and the connections between these

and other fields. While at the lab, Abelson began prescient studies of E.

coli (writing a book that presaged the microbe’s significance in microbiology)

and finding and exploring the significance of amino acids in fossils (presaging

the field of biogeochemistry). He also helped foster the careers of scientists

from around the world by inviting them to work at Carnegie.

A survey of Abelson’s many editorials at Science reveals a deep

concern for the connection between science and social good, for pushing scientists,

their societies, and governments to work better, as well as relishing in scientific

advances.

Hanson is deputy editor for

the physical sciences at Science in Washington, D.C.

Thomas Gold

David G. Howell

By the time I met Thomas Gold in 1991,

he had already been retired for 10 years from the directorship of Cornell University’s

Center for Radio-Physics and Space Research. It was in his home just weeks after

his golden retriever had given birth to eight adorable puppies. During this

first meeting, his attention leaped from the puppies to the stream of faxes

that were literally rolling across his office to an array of jars with black

gunk that he said contained methane from the mantle. It was the latter that

brought me to his home, and it was because of this topic that many geologists

know of Gold, who died on June 22 at age 84. But before elaborating on his thoughts

about primeval methane and his hypothesis of a “deep, hot biosphere,”

it is of interest to quickly review his career.

By the time I met Thomas Gold in 1991,

he had already been retired for 10 years from the directorship of Cornell University’s

Center for Radio-Physics and Space Research. It was in his home just weeks after

his golden retriever had given birth to eight adorable puppies. During this

first meeting, his attention leaped from the puppies to the stream of faxes

that were literally rolling across his office to an array of jars with black

gunk that he said contained methane from the mantle. It was the latter that

brought me to his home, and it was because of this topic that many geologists

know of Gold, who died on June 22 at age 84. But before elaborating on his thoughts

about primeval methane and his hypothesis of a “deep, hot biosphere,”

it is of interest to quickly review his career.

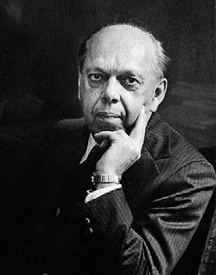

Astronomer and geologist Thomas Gold died

on June 22 at age 84. Image courtesy of Cornell University.

Born in Austria in 1920, Gold studied at Trinity College in Cambridge, England,

before he was placed in an internment camp for nearly two years. By nature,

he was a confident maverick, and this incident must only have strengthened his

intolerance for blind thinking and witless authorities. Undaunted, Gold continued

to study mathematics and befriended Hermann Bondi, who, along with Fred Hoyle,

would become an important colleague in his research in cosmology.

Immediately after his release from the camp, Gold worked for the British Admiralty

and lectured in advanced physics at Cambridge University. In 1956, he became

the chair of Harvard’s Astronomy Department and then moved on to Cornell.

A recipient of many awards, he was a member of the National Academy of Sciences,

the American Philosophical Society and, for seven years, the President’s

Space Science Panel.

Controversy was part of Gold’s nature, with his many theories always at

the edge of believability. He nimbly jumped from astrophysics to space engineering

to geology — from problems of radar ground clutter and the workings of

the inner ear to neutron stars and the magnetosphere (which he coined), to name

a few.

The Guardian referred to Gold as an “extroverted propagandist.”

He passionately believed in his ideas and wanted all of humanity to benefit

from them. That brings me back to the subject of my 1991 meeting with him about

the mantle.

When it came to his hypothesis that fossil fuels originate inorganically from

deep in Earth, many scientists reacted with disdain. Frankly, if Gold’s

idea of mantle gas is correct, won’t we all be better off? If not, what

have we lost? Science needs more Tommy Golds.

Howell is an emeritus

scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey.

Untitled Document

Philip Hauge Abelson passed away on

Aug. 1 at the age of 91. Although some of his early work in physics is most

often recognized, when forced to choose, he considered himself a geologist.

From the age of 30, Abelson never was satisfied working one job in one field.

He was an interdisciplinary researcher, director, president, editor and writer

— and avid walker and gardener just to fill out the day.

Philip Hauge Abelson passed away on

Aug. 1 at the age of 91. Although some of his early work in physics is most

often recognized, when forced to choose, he considered himself a geologist.

From the age of 30, Abelson never was satisfied working one job in one field.

He was an interdisciplinary researcher, director, president, editor and writer

— and avid walker and gardener just to fill out the day.

By the time I met Thomas Gold in 1991,

he had already been retired for 10 years from the directorship of Cornell University’s

Center for Radio-Physics and Space Research. It was in his home just weeks after

his golden retriever had given birth to eight adorable puppies. During this

first meeting, his attention leaped from the puppies to the stream of faxes

that were literally rolling across his office to an array of jars with black

gunk that he said contained methane from the mantle. It was the latter that

brought me to his home, and it was because of this topic that many geologists

know of Gold, who died on June 22 at age 84. But before elaborating on his thoughts

about primeval methane and his hypothesis of a “deep, hot biosphere,”

it is of interest to quickly review his career.

By the time I met Thomas Gold in 1991,

he had already been retired for 10 years from the directorship of Cornell University’s

Center for Radio-Physics and Space Research. It was in his home just weeks after

his golden retriever had given birth to eight adorable puppies. During this

first meeting, his attention leaped from the puppies to the stream of faxes

that were literally rolling across his office to an array of jars with black

gunk that he said contained methane from the mantle. It was the latter that

brought me to his home, and it was because of this topic that many geologists

know of Gold, who died on June 22 at age 84. But before elaborating on his thoughts

about primeval methane and his hypothesis of a “deep, hot biosphere,”

it is of interest to quickly review his career.