The sunlit side

of Earth faced a complete blackout of high-frequency radiotransmissions on Sept.

7, and emergency personnel responding to Hurricane Katrina may have experienced

communication difficulties as a result, according to the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The culprit was a solar flare — a violent

explosion in the sun’s atmosphere that erupts with energy equal to millions

of hydrogen bombs and hurtles radiation toward Earth. Such flares are also a

threat to astronauts, as they can bombard spacecrafts with high levels of radiation.

The sunlit side

of Earth faced a complete blackout of high-frequency radiotransmissions on Sept.

7, and emergency personnel responding to Hurricane Katrina may have experienced

communication difficulties as a result, according to the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The culprit was a solar flare — a violent

explosion in the sun’s atmosphere that erupts with energy equal to millions

of hydrogen bombs and hurtles radiation toward Earth. Such flares are also a

threat to astronauts, as they can bombard spacecrafts with high levels of radiation.

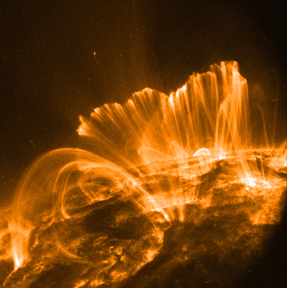

This image, taken by the TRACE spacecraft, shows the loop structures caused by the sun’s magnetic field. Scientists are combining similar images with a new model to help determine if solar flares are likely to occur. Courtesy of NASA/LMSAL.

Solar flares are not uncommon, however, and the potential devastation to technology and astronauts is driving researchers to improve existing prediction capabilities. By comparing solar images from two space observatories, NASA-funded scientists working at the Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, Calif., have found a new way to determine whether or not an event is likely by looking at how electrical currents fuel flares.

“This new result is not only interesting from an intellectual standpoint, but it also actually has potential impact on the affairs of the nation,” says Richard Fisher, director of the NASA Sun-Solar System Connection Division in Washington, D.C. “This is space science at its best.”

Solar flares occur when energy is suddenly released after building up in the sun’s magnetic field. Previously, scientists determined when a flare might occur by looking at complexity in the sun’s magnetic field; the more twisted and chaotic the field, the more likely it would be to snap like a rubber band. But that method is not always reliable because solar storms involve other players.

Electrical currents, for example, must be present to power flares, says Karel Schrijver, senior staff physicist at the Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory in Palo Alto, Calif. The currents deflect the magnetic field, warping it away from where it would be if there were no such currents, he says. Electrical currents, however, are difficult to study in the sun’s atmosphere because they cannot be directly measured.

But with images from SOHO and TRACE — space satellites that provide uninterrupted images of the sun for days in a row — Schrijver and colleagues have found an indirect way to infer the presence of a current. First, they looked at SOHO images that map the magnetic field on the sun’s surface. Based on these data, they created a computer model that extrapolates what that field would look like, free of current, in the sun’s atmosphere. Next, they compared this “current-free” model to the actual structure of the magnetic field apparent in TRACE images.

If at any time the images match, no electrical current is warping the actual field. But if the two pictures are clearly different, then researchers can infer that strong electrical currents are present. “Looking at the evolution of what happens at the solar surface over the two days leading up to a certain time,” Schrijver says, “we can tell with 90 percent accuracy whether there is enough current to drive the largest [flares] that occur on the sun.”

The work is of particular interest to the forecast analysis branch of the NOAA Space Environment Center that releases warnings, watches and forecasts to groups affected by space weather. With the new model, “we can give a prediction that might be good for a few days perhaps, of no activity expected,” says Joe Kunches, chief of NOAA’s forecast analysis branch. “Turning the coin over to try to predict imminent activity I think is a little tougher.”

Still, researchers can use the new method to predict “all-clear” times, which can be used to schedule activities such as spacewalks, Fisher says. “It allows you to avoid times that are less fortunate [for astronauts], and I think this will be an important thing as we return to the moon.”