Geotimes

News Notes

Geology and society

Moon rocks for sale!

Christina Reed

If you read the

above words on an Internet auction site or in the classifieds section of any newspaper,

the FBI and NASA want to know about it. Chances are the rocks are fake. But in

two court cases now pending in Florida, the U.S. government has seized legitimate

moon rocks for sale.

If you read the

above words on an Internet auction site or in the classifieds section of any newspaper,

the FBI and NASA want to know about it. Chances are the rocks are fake. But in

two court cases now pending in Florida, the U.S. government has seized legitimate

moon rocks for sale.

On July 20, the 33rd anniversary of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s 1969

Apollo 11 landing, the FBI arrested three people in Orlando, Fla., for the theft

of a 600-pound safe from a laboratory at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The safe contained lunar samples from every Apollo mission that landed on the

Moon as well as samples of the martian meteorite ALH84001, which is debated to

harbor martian microorganisms.

Although these were minute samples for scientific studies, NASA valued the 10

ounces of materials catalogued in the safe at approximately $1 million, says Lance

Carrington, Assistant Inspector General for Investigations at the NASA Office

of Inspector General (OIG). “The street value for that is based on a preliminary

assessment of what the market would bear,” he says.

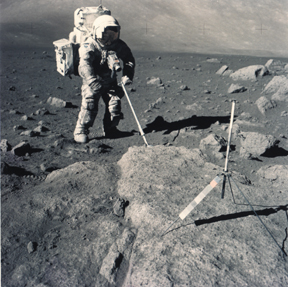

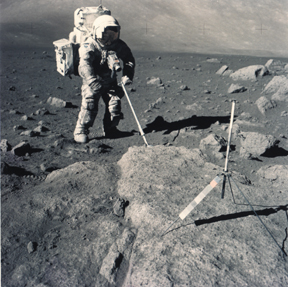

During the Apollo 17 mission, astronaut

and geologist Harrison H. "Jack" Schmitt collected moon rocks to bring

back to Earth. One of these rocks he dedicated to the children of the world

as the "Goodwill Rock." Photo courtesy of NASA.

The precedent for such a price came about in December 1993 when Sotheby’s

sold at auction a magnifying slide with three small lunar bits from the 0.7

pounds of lunar material Russia collected during its 1970s unmanned Luna missions.

The small particles from the Luna 16 probe sold for $442,500.

The price perhaps inspired retired military officer Roberto Agurcia Ugarte of

Honduras to look for a buyer for a moon rock chip he had acquired that was encased

in a hard plastic Lucite ball and attached to a plaque President Richard Nixon

had presented to the people of the Republic of Honduras in 1973.

As a token of goodwill after the success of the Apollo 11 mission, the United

States made 192 plaques displaying lunar dust to distribute to foreign nations

and U.S. governors. At the conclusion of the Apollo missions, a second round

of plaques were made from samples of the moon rock geologist and astronaut Harrison

H. “Jack” Schmitt collected and dedicated to the children of the world

during his Apollo 17 mission. This “Goodwill Rock” was sample number

70017 and provided the rock chip in each of the plaques made in 1973. The Republic

of Honduras received two plaques, one with a sample from the Apollo 11 mission

and the other with a lunar rock chip weighing 1.142 grams from the Apollo 17

Goodwill Rock, according to NASA files.

It is unknown when or how Ugarte came into possession of this later plaque.

Indeed his name is only known because he eventually found a buyer: fruit distributor

Alan Rosen.

Rosen,

65, who now lives in Pembroke Pines, Fla., was working in Honduras distributing

passion fruit juice and other items when he learned about the moon rock. “When

an intermediary friend of Ugarte’s told me he was trying to sell it for

a million dollars I laughed,” he says. “It was like someone trying

to sell me the Brooklyn Bridge.” He says he spent a year contemplating

the offer as he traveled between Honduras and the United States. While researching

the plaque’s history, Rosen read in a news article that NASA did not consider

the gifts to be U.S. property. He then purchased the plaque and pill-sized rock

chip in 1995 for what he says was a total of $50,000.

Rosen,

65, who now lives in Pembroke Pines, Fla., was working in Honduras distributing

passion fruit juice and other items when he learned about the moon rock. “When

an intermediary friend of Ugarte’s told me he was trying to sell it for

a million dollars I laughed,” he says. “It was like someone trying

to sell me the Brooklyn Bridge.” He says he spent a year contemplating

the offer as he traveled between Honduras and the United States. While researching

the plaque’s history, Rosen read in a news article that NASA did not consider

the gifts to be U.S. property. He then purchased the plaque and pill-sized rock

chip in 1995 for what he says was a total of $50,000.

At left is a photo of the plaque before

the United States presented it to Honduras in 1973, courtesy of NASA. At right

is the plaque displayed on Rosen's web

page. He covered the stars of the flag and the words "Republic of Honduras"

with paper, to keep from advertising that the plaque was Honduran, he says.

In 1996, Rosen submitted the moon rock without the plaque to David Lange of

Harvard University for analysis. “I certainly wanted it to be authenticated

prior to any sale,” Rosen says. “Of course I had an ulterior motive.

If NASA thought it was illegal they would pick it up and that would be the end

of it.”

Lange, unaware the rock was from Honduras, contacted James Gooding, then NASA’s

lunar sample curator at the Johnson Space Center. Gooding provided Lange with

the general descriptions of the diplomatic gifts from the Apollo 17 mission.

Earlier, Rosen had the base of the two-inch-wide Lucite ball cut and polished

to expose a small area of the rock chip. Lange performed the electron microprobe

analyses of the mineral phases and confirmed the rock did indeed belong to the

lunar sample 70017.

When Rosen returned to Harvard to learn of the results, “Nobody in trench

coats was waiting for me.” He then went to the Smithsonian Institution

in Washington to confirm that Lange had made the appropriate analyses. “I

wasn’t exactly trying to hide this,” he says.

At NASA, the OIG is in charge of detecting and preventing fraud, waste and abuses.

Beginning with Apollo 11, “as soon as we brought back lunar samples, NASA

had two problems: the issue of not exposing them to Earth’s environment

and also securing them to keep them from collectors or someone who wants to

benefit from the government’s efforts,” Carrington says. The astronauts

encased the material in nitrogen-filled containers for the return trip to Earth

where, upon landing, the samples were locked in a vault at the Johnson Space

Center. The bulk of the material — almost 650 pounds of the original 842

pounds of lunar rocks, core samples, pebbles, sand and dust brought back between

1969 and 1972 — is still in its pristine state within that vault.

Now that NASA had a legitimate collection of lunar material belonging to the

United States, the OIG had to monitor forgeries of moon rocks in the public

market. “As these things come up we look at them independently,” Carrington

says. In the last five to 10 years, with the increase of sales on the Internet,

NASA agents are finding more hoaxes but also getting the word out to the public.

On average only a couple cases a year lead to an actual arrest or seizure of

material. The rest are no more dangerous than someone making a joke, he says.

In October 1997, NASA agents began following Internet sales by a man in Arizona

who claimed to have decorated pictures with a sprinkling of moon rock particles.

He returned to the United States after fleeing to Canada, and NASA and FBI agents

arrested the man in New Milford, Conn. The case ended on Oct. 30, 2000. “Richard

Keith Mountain pled guilty to six counts of mail and wire fraud in connection

with a scheme to sell alleged moon rocks to interested buyers,” says Michael

Kreps, Special Agent in Charge of the NASA OIG in Long beach, Calif. “He

was sentenced to 21 months in prison, three years probation and 300 hours of

community service and ordered to pay $98,750 in restitution back to victims,

plus a $600 special assessment fee.”

In September 1998, NASA OIG linked up with the U.S. Postal Inspection Service

to launch a sting operation to catch forgeries of lunar rocks. Operation Lunar

Eclipse included an undercover agent placing an advertisement in USA Today that

read, “Moon Rocks Wanted.” Ironically, Rosen, who had a real moon

rock, responded to the ad on Sept. 29, 1998. At that point, NASA requested the

aid of U.S. Customs in the operation. During a meeting at a Miami restaurant,

Rosen offered the rock to the undercover agents for $5 million.

Agents seized the rock from its location in a safety deposit box in November

1998 with the argument that it was a piece of property considered stolen, smuggled

or clandestinely imported or introduced into the United States. “The moon

rock was seized by Customs Service agents because it was smuggled into the United

States without being properly declared on Customs Service forms, as is required

by law,” says Zach Mann, U.S. Customs special agent spokesman. If Martians

had brought down pieces of Mars for sale in the United States, as long as they

declared customs it would be duty free, Mann adds. “It is only legitimate

if someone has legal possession and authority to own it and as long as it is

declared.”

Since 2001, this moon rock has been involved in a unique case proceeding. The

case, entitled “United States v. One Lucite Ball Containing Lunar Material

(One Moon Rock) and One Ten Inch by Fourteen Inch Wooden Plaque,” is one

of forfeiture, where the court makes the final call as to the owner of the property.

Rosen is defending his claim to the property and has suggested that if a settlement

is made he would sell the rock at auction and use some of the money to establish

a small-loans banking business in Honduras. But the prosecuting attorney on

July 19 filed a motion for summary judgment. Judge Adalberto Jordan will determine

if the case will go to trial or if enough evidence exists to forfeit the property

to the U.S. government, which would most likely return the moon rock and its

plaque to the Republic of Honduras.

As for the stolen samples more recently recovered, the three suspects —

Thad Ryan Roberts, age 25; Tiffany Brooke Fowler, age 22; and Gordon Sean McWorter,

age 26 — are charged with Conspiracy to Commit Theft of Government Property

and Transportation in Interstate Commerce of Stolen Property. FBI agents arrested

a second woman — Shae Lynn Saur, age 19 — on July 22 in Houston for

Conspiracy. Three of the suspects, Roberts, Fowler and Saur, worked as student

employees at the Johnson Space Center.

Little did they realize their alleged plan to find a potential buyer before

stealing the lunar material set them up for failure. In May, someone posing

as “Orb Robinson” sent an e-mail to the Mineralogy Club of Antwerp,

Belgium, claiming: “Priceless Moon Rocks Now Available!!!” Another

e-mail was sent specifically to one of the club’s members, photographer

Axel Emmermann. “You have to be real dumb to think that a fake moon rock

would not be recognized as such if you sell it on a site that is scrutinized

by mineralogists,” Emmermann says, so he decided there was a chance the

rocks might be stolen. He contacted the FBI, which with NASA OIG agents followed

the case and convinced the suspects to bring the lunar material, stolen on July

13, to undercover agents in Orlando.

To report suspected criminal activity

contact NASA OIG

cyberhotline or the FBI.

Rosen,

65, who now lives in Pembroke Pines, Fla., was working in Honduras distributing

passion fruit juice and other items when he learned about the moon rock. “When

an intermediary friend of Ugarte’s told me he was trying to sell it for

a million dollars I laughed,” he says. “It was like someone trying

to sell me the Brooklyn Bridge.” He says he spent a year contemplating

the offer as he traveled between Honduras and the United States. While researching

the plaque’s history, Rosen read in a news article that NASA did not consider

the gifts to be U.S. property. He then purchased the plaque and pill-sized rock

chip in 1995 for what he says was a total of $50,000.

Rosen,

65, who now lives in Pembroke Pines, Fla., was working in Honduras distributing

passion fruit juice and other items when he learned about the moon rock. “When

an intermediary friend of Ugarte’s told me he was trying to sell it for

a million dollars I laughed,” he says. “It was like someone trying

to sell me the Brooklyn Bridge.” He says he spent a year contemplating

the offer as he traveled between Honduras and the United States. While researching

the plaque’s history, Rosen read in a news article that NASA did not consider

the gifts to be U.S. property. He then purchased the plaque and pill-sized rock

chip in 1995 for what he says was a total of $50,000.

If you read the

above words on an Internet auction site or in the classifieds section of any newspaper,

the FBI and NASA want to know about it. Chances are the rocks are fake. But in

two court cases now pending in Florida, the U.S. government has seized legitimate

moon rocks for sale.

If you read the

above words on an Internet auction site or in the classifieds section of any newspaper,

the FBI and NASA want to know about it. Chances are the rocks are fake. But in

two court cases now pending in Florida, the U.S. government has seized legitimate

moon rocks for sale.