Geotimes

Feature

A Unified Approach

to Diversifying the Earth Sciences

Jill Karsten

Sidebars:

Good News & Bad News: Diversity

Data in the Geosciences

The

Status of Women in the Geosciences

The word diversity, as defined in Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary,

is a simple, non-controversial term: “to make diverse, give variety to.”

Within the geosciences, the term is most often used in studies with a biological

flavor. For example, in an article published in the May 16, 2003, issue of Science,

David Jablonski and co-authors confirmed that a significant increase in the

diversity of marine animal speciation occurred during the Cenozoic Era. Interestingly,

controversy over earlier studies on this subject focused not on the presence

of diversity during the Cenozoic but on its absence in more ancient fossil sequences.

Skeptics explain the differences as a result of selective sampling or preservation.

In June, a conference was held in College Park, Md., to explore another situation

where diversity is lacking. In this case, it was not the geological record but

the geosciences community itself that was the target of discussion. The Joint

Society Conference on Increasing Diversity in the Earth and Space Sciences (IDEaSS

Conference) was motivated by concerns of equity, but more pragmatic considerations

also played a role. In an era of declining student enrollments, loss of geoscience

departments, upcoming “Baby Boomer” retirements and turbulent employment

conditions, the need to strengthen and revitalize the geoscientific workforce

has taken on new urgency. For many earth scientists, broadening participation

is an essential strategy in the battle to achieve this goal.

If we expect to succeed with future efforts to broaden participation in the

geosciences, we must understand the origins of our past failure to recruit and

retain a diverse population. A community-wide conversation on increasing diversity

is vital to achieving such understanding and identifying effective solutions

to the problem. The IDEaSS Conference was intended to begin this dialogue.

Students

at the IDEaSS Conference. Photo by Harvey Leifert, American Geophysical Union.

Students

at the IDEaSS Conference. Photo by Harvey Leifert, American Geophysical Union.

Defining common ground

Despite its simple definition, when the word diversity refers to people, many

interpretations are possible. To have a productive conversation, we must first

define a common ground and agree on the boundaries of the discussion. What do

we really mean by diversity?

Within the United States, the term most commonly refers to the concept of including

more women, cultural and ethnic minorities, and persons with disabilities in

fields traditionally dominated by white males. Recent studies reveal sustained

growth in the number of women participating in the earth and space sciences

at both undergraduate and graduate levels, although participation rates still

lag well behind current population demographics. Unfortunately, a disproportionate

number of women geoscience doctorates choose to pursue careers outside academe,

thus reducing their visibility as role models for female students considering

this profession (see sidebars).

The picture is dramatically worse for ethnic and cultural minorities, with the

geosciences ranking among the lowest for minority participation in science.

As Roman Czujko, director of the Statistical Research Center at the American

Institute of Physics (AIP), often observes, “The geosciences make physics

look good!” Failure to recruit substantial numbers of educated African

Americans, Hispanic Americans and Native Americans into the geosciences is due

to many complex causes. Significant population growth in these combined communities

is projected over the next decade, to the point where they will become the “underrepresented

majority” unless things change. For persons with disabilities, who comprise

nearly one-fifth of the adult population, available information on their status

is insufficient. A large portion of the next generation of geoscience students

and professionals within the United States will need to originate from all of

these currently underutilized sectors of the population.

Diversity also refers to the increasingly international and multicultural community

engaged in our profession. Many of the large U.S.-owned energy corporations

now have worldwide operations, internationally distributed management, or have

been bought out or merged into foreign companies. Within some industry sectors,

such as mining and mineral resources, most of the job market lies outside the

United States. Evolution in geoscience employment opportunities — an outgrowth

of both economic globalization and the increasing porosity of national borders

— has increased demand for a skilled and mobile geoscientific workforce

prepared to tolerate and work effectively within many different cultural settings.

Globalization

is also reflected in the memberships and programs of the scientific societies

and professional organizations that support the earth science community. More

than 50 percent of the members in the Society of Economic Geologists now live

outside the United States. “A-List” organizations — those with

“American” in their name — face increasing challenges to broaden

their attitudes and activities in ways that serve the distinct interests of

their international members. Increased use of the more neutral AGU moniker by

the American Geophysical Union, which has 12,000 non-U.S. members in 130 countries,

is a sign of the times.

Globalization

is also reflected in the memberships and programs of the scientific societies

and professional organizations that support the earth science community. More

than 50 percent of the members in the Society of Economic Geologists now live

outside the United States. “A-List” organizations — those with

“American” in their name — face increasing challenges to broaden

their attitudes and activities in ways that serve the distinct interests of

their international members. Increased use of the more neutral AGU moniker by

the American Geophysical Union, which has 12,000 non-U.S. members in 130 countries,

is a sign of the times.

The American Geophysical Union (AGU) brought two groups of high school students,

from the Greater Richmond Area Higher Education Consortium and the Model Secondary

School for the Deaf at Gallaudet University, to the 2002 Spring AGU Meeting

— for a special symposium on earth and space sciences and a high school

poster session, seen here. Photo by Harvey Leifert, AGU.

Rapidly changing disciplinary boundaries offer a third viewpoint on diversity.

Today’s geoscientists are a varied lot that include atmospheric scientists,

planetary geologists, oceanographers, space physicists, hydrologists and even

biogeologists among their ranks. Yet we wrestle with the proper taxonomy for

our disciplines — how to draw the professional lines, how to count the

bodies? Are environmental scientists included? What about GIS professionals

or geomorphologists, who are spawned more often from geography departments than

from geology departments? Seemingly trivial questions, perhaps, but they are

critically important in defining the present geoscience community, assessing

future workforce needs and gauging the need for diversity. Add in the complexities

of counting a global and transient workforce, and it is easy to see how the

arguments can become murky and imprecise.

With so many perspectives and without knowing reliably and quantitatively who

we really are as a professional community, it is challenging to have a coherent

dialogue on diversity. In my view, we must consider all of these perspectives,

for they are not easily separable. A robust and fully representative U.S. workforce

is as critical to the health of our profession as is a portable, adaptable and

global network of scientists.

In spite of the natural allure and societal relevance of our disciplines, our

community has not always succeeded in attracting the most creative and brightest

minds from a broad multicultural spectrum to the earth sciences. We can no longer

afford to assume passively that this situation will resolve itself. Part of

the solution lies in aggressively recruiting more students across the board,

developing effective mechanisms to keep them in the field once recruited, and

ensuring that we pay particular attention to those communities that have traditionally

been forgotten along the way. As noted by Juan Burciaga, a professor at Bryn

Mawr College: “Good programs will work for ALL students, not just minorities;

but their impact will be the greatest for minority students.”

Building a community view

On June 10, amid the backdrop of U.S. Supreme Court affirmative action deliberations,

nearly 70 scientists and society staff members convened at the American Center

of Physics to begin a three-day conversation on increasing diversity in the

geosciences. Twenty-seven different scientific organizations and six federal

agencies attended the IDEaSS Conference. In the room were “Goliaths,”

such as the 39,000-member-strong American Association of Petroleum Geologists,

as well as “Davids” like the 250-member Association of Earth Science

Editors, but each participated with equal voice. Minority-membership organizations,

such as the National Society of Hispanic Physicists and the National Association

for Black Geologists and Geophysicists, attended as well. Several of the major

physics societies, which are equally concerned about diversity, joined in the

discussion.

The concept

of a multisociety conference on diversity originated with AGU’s Committee

on Education and Human Resources (CEHR) as one component of its new diversity

plan, released in May 2002 (www.agu.org/sci_soc/education/diversity.html).

While the plan targets AGU programs, CEHR recognized that well-coordinated partnerships

might best achieve several key objectives. CEHR identified two main goals for

the conference. The first was to educate participants about the need for increasing

diversity and to identify some of the successful diversity programs currently

offered. The second goal was to explore the concept of a multisociety coalition

on diversity.

The concept

of a multisociety conference on diversity originated with AGU’s Committee

on Education and Human Resources (CEHR) as one component of its new diversity

plan, released in May 2002 (www.agu.org/sci_soc/education/diversity.html).

While the plan targets AGU programs, CEHR recognized that well-coordinated partnerships

might best achieve several key objectives. CEHR identified two main goals for

the conference. The first was to educate participants about the need for increasing

diversity and to identify some of the successful diversity programs currently

offered. The second goal was to explore the concept of a multisociety coalition

on diversity.

An elementary school student looks at

rocks in thin sections while attending the 1997 School of Ocean and Earth Science

and Technology Open House at the University of Hawaii at Manoa — one of

several outreach programs to bring students from underrepresented communities

onto university campuses. Photo courtesy of Jill Karsten.

The conference focused on the unique role that scientific societies can play

in promoting diversity in the geosciences, although some consideration was also

given to how the societies could mesh their efforts with those of academia,

government and industry. The emphasis was on the first definition — the

issue of increasing recruitment and retention of women, minorities and persons

with disabilities. A multisociety planning committee, chaired by James H. Stith,

vice president of AIP’s Physics Resources Division, developed the conference

agenda. Presentations reviewed current demographics in the geoscience community

and explored topics such as gender differences that contribute to decisions

to leave the profession, initiatives to increase technological infrastructure

at tribal colleges and universities, and new partnerships to support programs

for minority graduate scientists.

A poster session on the first evening highlighted existing diversity programs

within professional societies and was followed by a panel discussion that explored

the essential ingredients of effective programs. The second evening highlighted

diversity programs sponsored by federal agencies and included a report about

new initiatives to improve cross-agency coordination. A formal conference report

will be available this fall.

Coordinating efforts

“There have been a lot of well-intentioned programs in the last 28 years;

the bottom line is that we haven’t been very effective,” suggested

John Snow, dean of the University of Oklahoma’s College of Geosciences.

“It’s not a pipeline problem, it’s a spigot problem,” argued

Lawrence Norris of the National Society of Black Physicists. The remarkably

frank and often passionate attitudes shared by participants during plenary and

break-out group discussions proved to be a hallmark of the conference. Alternating

between respectful disagreement, realism and optimism, conference attendees

remained focused on setting an ambitious goal and agenda for the community.

All participants felt strongly that working in partnership was essential to

making progress, but recognized the many challenges to getting official buy-in

from the organizations they represented. One of the greatest obstacles will

be to create a coordinated program that can mesh with the many different missions

and priorities of these various organizations.

Deliberations on that question consumed much of the final day: Should we coordinate,

collaborate or form a coalition? Carolyn Randolph, outgoing president of the

National Science Teachers Association, outlined the challenges of building formal

coalitions and making them work. Subsequent discussions considered the pros

and cons of establishing a formal joint society coalition on diversity. A coalition

allows participants to speak with a unified voice — an obvious strength

of such an arrangement — and brings added value by leveraging resources,

avoiding duplication and steering the allocation of funding agency priorities.

Potential drawbacks include the more cumbersome communication and organizational

processes that a formal structure would entail.

A resolution drafted during the conference frames the rationale behind and priorities

for a collaborative society effort on diversity. The final language is still

undergoing comment and revision. We observed significant overlap between the

recommendations identified during the IDEaSS Conference and those contained

in the draft report of the 2003 Task Force on National Workforce Policies for

Science and Engineering, issued by the National Science Board (NSB) last spring

and summarized by NSB Senior Policy Analyst Jean Pomeroy. The draft IDEaSS Conference

resolution endorses the recommendations of the NSB report and offers to help

with their implementation within the earth, ocean, space and physical sciences

communities.

An initial priority is to establish a Web-based, centralized and comprehensive

clearinghouse with information on the need for increasing diversity, related

background materials and a digest of resources and best practices that can be

used by organization members and their home institutions to help encourage diversity.

Providing this community resource through the Digital Library for Earth System

Education, a national grass-roots program funded by the National Science Foundation,

seems most logical. A second priority is to develop and promote a centralized

repository of culturally sensitive career information and biographies or profiles

of scientists and other professionals in the earth and space sciences, to which

any society can contribute.

The goal now is to sustain the momentum of the IDEaSS Conference by garnering

broader and more formal support for a joint society effort on increasing diversity.

In the next four months, conference participants will work through the governance

structures of their own organizations to seek support for the final draft resolution

and coalition concept. They will also determine what resources their organization

might be willing to commit to such an effort. We recognize that some attrition

will occur during this phase, but also hope that groups unable to attend the

conference will now join the cause.

Webster’s offers a second common definition for diversity. It concerns

a strategy “to balance (as an investment portfolio) defensively.”

As we continue our dialogue on the status of the earth science workforce and

contemplate our future investments in maintaining its vigor, it is imperative

that we pursue diversification. This is sound business practice. New attitudes

and innovative strategies will be necessary. The IDEaSS Conference has begun

to identify what those might be. Eventually, we will need to move beyond conversation

and put our words into action. At that step, a community-wide commitment will

be crucial.

Good

News & Bad News: Diversity Data in the Geosciences

Roman Czujko and Megan

Henly

Higher education in the United States is a large and competitive system.

Each year, more than 1.2 million people earn bachelor’s degrees in

the United States. The geosciences are comparatively small with about

4,000 bachelor’s degrees awarded annually in geology, atmospheric

sciences, geophysics, oceanography and space science combined. Similarly,

more than 42,000 people earn Ph.D.s in the United States each year, but

only about 800 of those degrees are in the geosciences.

Here we provide a snapshot of two illustrative trends regarding diversity

in geoscience education: the rise in participation among females at the

bachelor’s level and the sobering statistics on ethnic minority participation

in the geosciences. The U.S. Department of Education collected the bachelor’s

level data and the National Science Foundation collected the Ph.D. data.

Gender on the undergraduate

level

Because the geosciences are small compared to the total U.S. higher-education

system, large swings in the demographic profile of students are visible

over a short time scale. One such example is gender diversity in the geosciences.

The representation of women among bachelor’s degree recipients in

the geosciences has nearly doubled over the last 15 years.

The growth rate for the participation of women in the geosciences has

been very strong, going from 22 percent in 1986 to 40 percent for the

bachelor’s class of 2000. However, the levels are well below the

average for all fields. The representation of women among geoscience bachelor’s

is ahead of several related disciplines like physics and engineering,

but lags behind other fields, such as mathematics, chemistry and the life

sciences.

In addition, the participation of women is uneven by specialty among the

geosciences. Geology, in part because it is relatively large, displays

representation rates that are consistent with the average for all geoscience

bachelor’s. Oceanography grew the fastest, with the representation

of women among bachelor’s degrees jumping from 18 percent in 1986

to 49 percent in 2000. Women earned barely more than 20 percent of the

bachelor’s degrees awarded in atmospheric science in 2000.

To a significant extent, the choices that women make are driving higher

education. Currently, women earn about 58 percent of all bachelor’s

degrees. This is the result of a gradual increase in the participation

of women in higher education — a trend that’s been in progress

for decades.

The National Center for Education Statistics projects that this trend

will continue and that women will earn at least 60 percent of the bachelor’s

degrees awarded in 2010. Thus, staying competitive with other fields will

depend, in part, on the ability of the geosciences to attract and retain

women into the discipline.

Ethnic minorities

The

record for attracting and retaining ethnic minorities into the geosciences

is very poor. In fact, at the bachelor’s degree level, no other scientific

field has a lower participation among either African Americans or Hispanic

Americans than do the geosciences. Of all bachelor’s degrees awarded

in the United States in 2000, African Americans and Hispanic Americans

earned 8.7 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively. Among geoscience bachelor’s

awarded that year, African Americans and Hispanic Americans earned a mere

1.3 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively. The

record for attracting and retaining ethnic minorities into the geosciences

is very poor. In fact, at the bachelor’s degree level, no other scientific

field has a lower participation among either African Americans or Hispanic

Americans than do the geosciences. Of all bachelor’s degrees awarded

in the United States in 2000, African Americans and Hispanic Americans

earned 8.7 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively. Among geoscience bachelor’s

awarded that year, African Americans and Hispanic Americans earned a mere

1.3 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively.

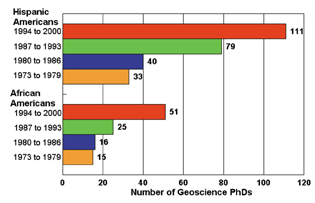

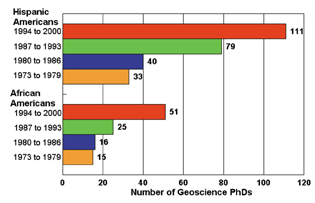

Over the past 28 years, out of the approximately 20,000 people who earned

geoscience Ph.D.s in the United States, only 263 were Hispanic American

and only 107 were African American. Graph provided by Roman Czujko and

Megan Henly.

To put these paltry participation rates in a different light, more than

100,000 African Americans and more than 75,000 Hispanic Americans earned

bachelor’s degrees across all fields during the academic year 1999-2000.

However, during that year, only 55 of the African Americans and 125 of

the Hispanic Americans earned bachelor’s degrees in any of the geosciences.

The record for the geosciences at the Ph.D. level is, arguably, worse

still. The number of minorities earning geoscience>>

Ph.D.s is still extremely small. Over the last 28 years, about 20,000

people earned geoscience Ph.D.s in the United States. Of them, only 107

were African Americans and 263 were Hispanic Americans. It should be noted

that these trends reflect more than the size of geosciences relative to

other Ph.D. fields. For example, over the last 28 years, more than 32,600

African Americans and more than 21,000 Hispanic Americans earned Ph.D.s

across all fields in the United States. Clearly, very, very few of them

did so in any of the geosciences. On the positive side of the ledger,

the number of both African Americans and Hispanic Americans who earned

geoscience Ph.D.s over the past seven years is more than three times larger

than in the mid-1970s.

These statistics are only the tip of a much larger data iceberg. Two reports,

published by the American Institute of Physics, contain a great deal of

information about minorities in the sciences. One report describes the

participation of African Americans in physics and in the geosciences.

The other describes the participation of Hispanic Americans in physics

and in the geosciences. These reports include lists of universities that

have produced the largest numbers of minorities in the geosciences, and

were made possible by the support of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Similarly, there is a wealth of data on women in the geosciences. A copy

of a poster paper presented at the AGU meeting in December 2002 is also

available on the Web. To download any of these reports, please see

the list below.

Czujko is the Director

of the Statistical Research Center of the American Institute of Physics

(AIP). Henly also works at AIP. The Statistical Research Center conducts

studies that document the education trends in physics and related disciplines

in the United States from high school through graduate school.

|

Karsten is manager of education

and career services at the American Geophysical Union (AGU). Prior to joining

AGU, she spent 12 years as a research faculty member in the Department of Geology

and Geophysics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where she investigated mid-ocean

ridge processes in the northeast and southeast Pacific Oceans. E-mail: jkarsten@agu.org.

For more information about the IDEaSS Conference program, participants

and outcomes, click

here. The conference was funded by NASA, the National Science Foundation,

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Geological Survey

and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Suggested Further Reading:

The

Quiet Crisis: Falling Short in Producing American Scientific and Technical Talent,

by Shirley Ann Jackson, Building Engineering and Science Talent position paper,

12 pp., 2002.

Land

of Plenty: Diversity as America's Competitive Edge in Science, Engineering and

Technology, Report of the Congressional Commission on the Advancement

of Women and Minorities in Science, Engineering and Technology Development (CAWMSET),

104 pp., 2000.

NSF 01-53: Report

of the Geosciences Diversity Workshop, National Science Foundation,

2000.

Back to top

Students

at the IDEaSS Conference. Photo by Harvey Leifert, American Geophysical Union.

Students

at the IDEaSS Conference. Photo by Harvey Leifert, American Geophysical Union.

Globalization

is also reflected in the memberships and programs of the scientific societies

and professional organizations that support the earth science community. More

than 50 percent of the members in the Society of Economic Geologists now live

outside the United States. “A-List” organizations — those with

“American” in their name — face increasing challenges to broaden

their attitudes and activities in ways that serve the distinct interests of

their international members. Increased use of the more neutral AGU moniker by

the American Geophysical Union, which has 12,000 non-U.S. members in 130 countries,

is a sign of the times.

Globalization

is also reflected in the memberships and programs of the scientific societies

and professional organizations that support the earth science community. More

than 50 percent of the members in the Society of Economic Geologists now live

outside the United States. “A-List” organizations — those with

“American” in their name — face increasing challenges to broaden

their attitudes and activities in ways that serve the distinct interests of

their international members. Increased use of the more neutral AGU moniker by

the American Geophysical Union, which has 12,000 non-U.S. members in 130 countries,

is a sign of the times. The concept

of a multisociety conference on diversity originated with AGU’s Committee

on Education and Human Resources (CEHR) as one component of its new diversity

plan, released in May 2002 (

The concept

of a multisociety conference on diversity originated with AGU’s Committee

on Education and Human Resources (CEHR) as one component of its new diversity

plan, released in May 2002 ( The

record for attracting and retaining ethnic minorities into the geosciences

is very poor. In fact, at the bachelor’s degree level, no other scientific

field has a lower participation among either African Americans or Hispanic

Americans than do the geosciences. Of all bachelor’s degrees awarded

in the United States in 2000, African Americans and Hispanic Americans

earned 8.7 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively. Among geoscience bachelor’s

awarded that year, African Americans and Hispanic Americans earned a mere

1.3 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively.

The

record for attracting and retaining ethnic minorities into the geosciences

is very poor. In fact, at the bachelor’s degree level, no other scientific

field has a lower participation among either African Americans or Hispanic

Americans than do the geosciences. Of all bachelor’s degrees awarded

in the United States in 2000, African Americans and Hispanic Americans

earned 8.7 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively. Among geoscience bachelor’s

awarded that year, African Americans and Hispanic Americans earned a mere

1.3 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively.