A planet

with two, three or even four suns, while strange for us earthlings (except for

in movies such as Star Wars), is not entirely unusual in the universe.

More than half of all planets form with multiple stars. But a recent planet

found in a triple-star system perplexes astronomers because, according to current

models of planetary formation, it should not exist.

A planet

with two, three or even four suns, while strange for us earthlings (except for

in movies such as Star Wars), is not entirely unusual in the universe.

More than half of all planets form with multiple stars. But a recent planet

found in a triple-star system perplexes astronomers because, according to current

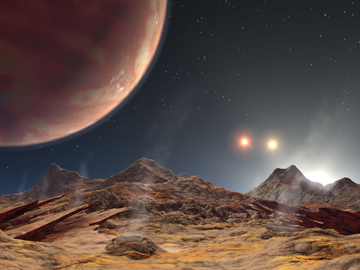

models of planetary formation, it should not exist. An artist’s interpretation shows the view from a hypothetical moon in orbit around a planet that has three suns. The gas giant travels around a single star, both of which are orbited by a nearby system of two stars. Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The planet orbits at a distance of only 7.5 million kilometers from the primary star of system HD 188753 (about 5 percent of the distance between Earth and the sun); it circles the star in just over three days, instead of the 365 days for Earth. But it was a binary star system (two stars that orbit in unison) orbiting the primary star and planet that struck Maciej Konacki of Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., as peculiar. According to Konacki’s paper in the July 14 Nature, the companion binary of HD 188753 orbits exceedingly close to the primary star, compared to other multiple-star systems — so close in fact that its gravity should have stripped away the materials needed to build a planet.

Planet-building materials exist in early solar systems within a disk around a star. Over time, the icy debris clumps together and, like a growing snowball, eventually reaches the size of a planet. Some conditions, however, restrict the size and location of such planet nurseries. Alycia Weinberger, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, says that intense heat melts away any potential planet-building materials close to a star. “To condense material into a planet, it needs to be fairly cool,” Weinberger says.

Prior to the discovery of the planet in HD 188753, scientists knew of large planets in other systems that also orbited too close to a hot star to have formed there. To explain the existence of these planets that astronomers call “hot Jupiters,” they calculated that the planets could form in cooler locations farther out and then migrate in. “Basically there’s an interaction between the planet and the disk and that causes the planet to slowly spiral in, and eventually it stops someplace close to the star,” Weinberger says. “That’s the accepted mechanism for all of these so-called hot Jupiters.”

Konacki says, however, that HD 188753 poses a significant complication. Even at a distance from the primary star, gravity from the system’s closely orbiting companions would have demolished any potential building material. “The difficulty in this system is how you form the planets to begin with.”

It is possible, Konacki says, that cold planet-building materials can reside closer to a star than previously believed, so that the planet formed in its current orbit. Another possible explanation is that the orbits of the stars were different during the time of planet formation — far enough apart as not to affect the debris disk. “We may not know for this particular system, ever, what its original configuration was at the time the planet formed,” Weinberger says. But “how important this discovery is for planet-formation theory depends on whether you believe that it formed in its current configuration or not.”

If it turns out that the planet indeed coalesced with the companion and primary stars of HD 188753 as close together as they are today, astronomers will have to scrap current ideas about how planets form. Weinberger says, “We would really have to revise planet-formation theories to be able to keep the planet in the system.” Konacki agrees, and holds that modifications to current theory could explain the formation of the planet. “Let’s wait for what the theorists have to say,” Konacki says.

Konacki continues to survey 450 multiple-star systems to find out if similar arrangements are common. Looking at systems dissimilar to our own is an important first step in learning about the nuances of planet formation. “The planets have turned up it seems in the utmost creative places,” Weinberger says. “That’s lots of fun because now it’s up to us to try and figure out how that happened.”