Geotimes

Untitled Document

Web Extra

Friday, April 29, 2005

Drought in the Horn of Africa

Eastern Africa is suffering from a severe drought for the sixth year in a row,

which, according to climatologists, could endanger the upcoming harvest season

and put the area at risk of famine and water shortages this year.

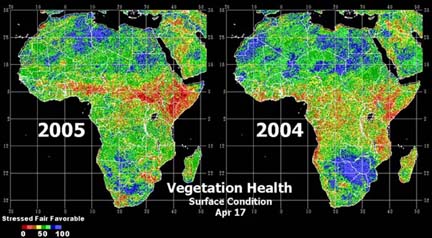

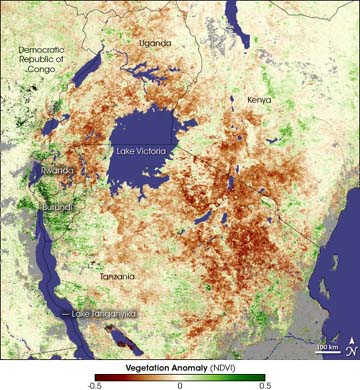

Using satellite images, scientists have been monitoring the dry spell in parts

of Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia, known as the Horn of Africa, since January.

The imagery shows that regions of the area at risk may not growing enough vegetation.

The

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA),

Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellites (POES)

circle Earth, providing two images a day of the entire planet. Using the Advanced

Very High Resolution Radiometer sensor, the scientists can measure the reflectivity

of total vegetation, based on the chlorophyll content that gives plants their

green color, says Douglas Le Comte, a drought specialist with NOAA's Climate

Prediction Center.

The

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA),

Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellites (POES)

circle Earth, providing two images a day of the entire planet. Using the Advanced

Very High Resolution Radiometer sensor, the scientists can measure the reflectivity

of total vegetation, based on the chlorophyll content that gives plants their

green color, says Douglas Le Comte, a drought specialist with NOAA's Climate

Prediction Center.

"Research has shown that crops under stress reflect differently than healthy

plants," Le Comte says. "If the area is not 'greening' up, that's

a good sign that there's a drought." The researchers with NOAA say the

minor agricultural season, which runs from March through May, may not be able

to provide enough food to sustain people until the next harvest season.

This satellite image depicts the amount

of chlorophyll reflecting from vegetation in the Horn of Africa. The brown areas

are a result of wilting due to the current drought conditions. Image courtesy

of NASA Earth Observatory.

Although this is the sixth year in a row that the Horn of Africa has been exposed

to a long dry spell, not all of the afflicted areas will be at risk of starvation,

Le Comte says. "You can have a bad growing season and not have it be too

detrimental. If the last harvest was good, there will be enough food for crisis

time," he says.

That is the case in Somalia, where a bumper crop of sorghum will hold them

through the dry spell. Kenya, however, has experienced two seasons in a row

of below-normal rains, and is going into this season with serious problems,

Le Comte says. And according to the United Nations' World Food

Programme (WFP), the country will have a deficit of 60,000 tons of food

until the August harvest season. In Ethiopia, 49 percent of the population is

malnourished, and in 2004 WFP sought 871,000 tons of food aid for the country.

Despite the dismal outlook, the area is now beginning to see some widespread

rains, and NOAA forecasts show more wet weather on the way. "We've had

some dry spells, but it's turning wet," Le Comte says, "which is good

unless it's excessive." In the extreme, the rainfall can destroy agricultural

yields and create risk of flooding, something researchers are watching closely.

Typically, April through June is the major rainy season, called "Gu,"

and for Eastern Africa, the season brings with it a risk of flooding and landslides.

In 2002, according to NASA's Earth Observatory for natural hazards, tens of

thousands of Kenyans were driven from their homes, and in Rwanda, almost 50

people died from flooding and landslides.

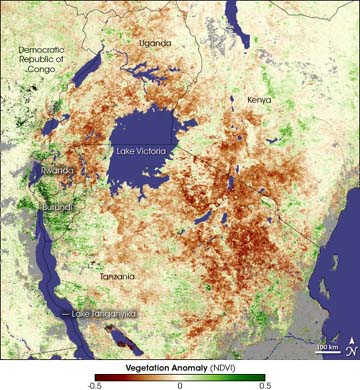

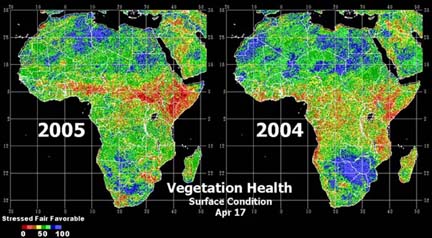

These maps compare the health of vegetation

across Africa during 2004 (on right) and 2005 (left). The red color depicts

areas experiencing extreme drought, with the majority in Kenya, Somalia and

Ethiopia in the eastern potion of the continent. Image courtesy of NOAA.

Due to climate change, rainfall extremes are also increasing not only in Africa,

but worldwide, says Kevin Trenberth, head of the Climate Analysis Section at

the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), who is not affiliated with

the NOAA research. Climate change creates a pattern that is of "heavier

rains, but perhaps fewer and farther between."

An area's vulnerability to drought depends on the amount of rainfall, Trenberth

says; too much or too little can affect soil moisture and the water levels of

lakes and rivers. "Certainly, water resources are at risk with these [climate]

changes," Trenberth says. "Of course it is complicated regionally,"

not only by agriculture and soil type, but also by a community's ability to

adapt to changes in climate.

For instance, semi-arid regions around the world may be more prone to drought

conditions, but they may also be more prepared for water shortages, Trenberth

says. But when relatively wet areas, such as the East Coast of the United States,

suffer drought, he says that poor water management and wasteful practices can

intensify the predicament. Globally, these situations can be further complicated

by irrigation systems, distorting the picture of soil moisture, hydrological

levels of lakes and streams, and precipitation. Indeed, Le Comte says, "it's

not a simple picture."

Still, Trenberth says, "drought seems to be increasing around the world,"

with warmer temperatures creating more evaporation and thus drier conditions.

According to the Climate Prediction Center, Afghanistan, parts of the Caribbean

and Central America, and the Mekong Basin region of Asia are all experiencing

severe drought, with portions of their populations at risk of food and water

shortages. In the United States, areas of the Pacific Northwest,

Wyoming and Montana are also in extreme drought conditions, Trenberth says.

Even with record rainfalls and heavy snowpack throughout the winter, the lake

levels remain very low, perpetuating a five-year-long dry spell in the region.

Laura Stafford

Links:

"New

explanations for Western drought," Geotimes, August 2004

"Western

Aquifers Under Stress," Geotimes, May 2004

NOAA

homepage

NOAA's

Climate Prediction Center

NOAA's

Famine Early Warning System Network

NOAA

Satellite and Information Service, POES

African

rainfall estimates from 2001 to the present

United Nations World

Food Programme in Africa

NASA's

Earth Observatory

Back to top

Untitled Document

The

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA),

Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellites (POES)

circle Earth, providing two images a day of the entire planet. Using the Advanced

Very High Resolution Radiometer sensor, the scientists can measure the reflectivity

of total vegetation, based on the chlorophyll content that gives plants their

green color, says Douglas Le Comte, a drought specialist with NOAA's Climate

Prediction Center.

The

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA),

Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellites (POES)

circle Earth, providing two images a day of the entire planet. Using the Advanced

Very High Resolution Radiometer sensor, the scientists can measure the reflectivity

of total vegetation, based on the chlorophyll content that gives plants their

green color, says Douglas Le Comte, a drought specialist with NOAA's Climate

Prediction Center.