|

FEATURE

The Agricultural Impact of Global Climate Change: How Can Developing-Country Farmers Cope?

Nathan Russell

Planning for Food After “Doomsday”

|

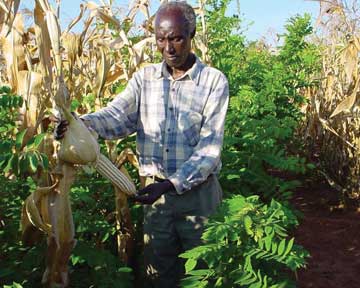

| Making more productive use of water for agriculture, especially in dry areas of the developing world, is critical for enabling small farmers to adapt to the consequences of global climate change. Photographs are by the International Water Management Institute. |

|

No one understands better than farmers how weather affects people and their land, especially when it takes a turn for the worse. That’s why farmers around the world talk and worry about the weather obsessively. But now, emerging weather patterns have a lot of other people worried, too, and their concerns are well-founded.

According to a recent report of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the average temperature of Earth’s surface, having already risen by 0.7 degrees Celsius in the last century, is expected to increase by an average of about 3 degrees Celsius over the next century, assuming greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at current rates. Even the minimum predicted temperature increase, 1.4 degrees Celsius, will represent a profound change that is unprecedented in the last 10,000 years.

The scientific evidence behind these projections is unequivocal, leaving “no doubt as to the dangers mankind is facing,” says Yvo de Boer, executive secretary of the U.N.’s Framework Convention on Climate Change. One of the gravest concerns facing the world, and especially developing countries, is agriculture’s vulnerability to climate change.

The Risk Factors

Part of the danger to agriculture comes from extreme weather events, such as stronger storms, longer droughts and prolonged flooding events. Using computer-based simulation models, scientists predict these extreme events will occur with greater frequency, especially in the tropics. In addition, more subtle changes in rainfall patterns, together with rising temperatures, may shorten growing seasons in some areas, reducing crop productivity.

Never before have so many people been vulnerable to weather fluctuations, partly because never before has Earth been so densely populated, and partly because so many rural populations are poor. According to World Bank estimates, rural populations account for nearly 75 percent of the approximately 1.2 billion people who live in extreme poverty. Poverty, because it limits options, is a major reason that developing-country farmers are vulnerable to global climate change.

Another factor is the steady degradation during recent decades of the soil, water, forests and other plant resources on which rural livelihoods depend. This has resulted in large part from the intensification and expansion of agriculture in response to a growing demand from Earth’s rapidly expanding human population for food, feed and fiber. Lacking more sustainable alternatives, farmers have often been obliged to adopt practices — such as continuously growing one crop and overusing chemical fertilizers and pesticides — that lead to biodiversity loss, soil erosion and water contamination.

Sub-Saharan Africa, the world’s poorest region and one very dependent on agriculture, brings the problem into sharp focus. An estimated 500 million hectares of its agricultural land are already degraded, according to soil scientists. Moreover, 95 percent of the region’s cropland is rainfed, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, and rainfall patterns are already quite erratic.

With climatic challenges on the horizon, how farmers in Africa and elsewhere will keep pace with the demand for food remains to be seen. But their only hope of creating better livelihoods for themselves is through income growth and effective stewardship of natural resources.

Mapping the Menace

The potentially dire consequences of global climate change, to paraphrase literary figure Samuel Johnson, are wonderfully concentrating the minds of agricultural scientists, development professionals and policymakers around the world.

Among them are the approximately 8,000 scientists and staff of the 15 centers supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, or CGIAR. Its work represents the largest public investment in international agricultural research. The CGIAR centers and their partners in governmental and nongovernmental organizations have been working for years to help farmers cope with the effects of variable and severe weather.

CGIAR scientists have significantly advanced the understanding of what specific consequences rural populations will face in particular places as a result of climate change. Several years ago, researchers in Africa and Latin America, using weather and crop simulation models, mapped the impact on both regions’ maize production. Models predict a 10 percent decline in maize productivity by 2055. Moreover, the results reveal significant variation in the effects of climate change from one place to another, indicating where devastating maize crop losses could be expected.

Researchers have also mapped the impacts of climate change on wild species related to three food crops: cowpea, peanut and potato. If the climate changes as researchers expect, 22 out of 51 wild species of peanut, for example, will most likely become extinct by 2050, and the area covered by these species will shrink to 10 percent of its present size.

In addition to foreseeing the fate of plants on which people depend, CGIAR scientists are mapping the vulnerability of agricultural systems, based on a variety of biophysical and social factors. A recent study carried out in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, identified “hotspots” of vulnerability to the combined menace of climate change and poverty.

The maps produced by such studies provide an early warning as to which plant species, agricultural systems and rural communities are at greatest risk in the long term.

Climate-Resilient Food

If farming communities are to successfully adapt to climate change, they will need crop varieties and livestock breeds possessing greater tolerance to stresses such as drought and heat. Research has significantly advanced in developing hardier crop varieties through conventional breeding methods, and the application of tools from molecular biology is speeding the process. One challenge is to make more extensive use of crops’ wild relatives. These contain genes for traits such as drought tolerance, which could prove useful for adapting crops to harsher conditions. “Climate-resilient” varieties resulting from crop improvement programs have already reached farmers’ fields, and more are in the pipeline.

|

| Rice in the Philippines is selectively bred for tolerance to salinity. This trait will become increasingly important, as greater variability in rainfall prompts rice producers to rely more heavily on irrigation, which can lead to salinization. Photograph is by the International Rice Research Institute. |

Maize breeders working in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, have developed more than 50 new varieties that are tolerant to drought, and these are already being grown on at least a million hectares. Part of the secret behind this triumph is a novel breeding method, in which hundreds of small farmers take part in testing new varieties under harsh growing conditions. Varieties selected on the basis of field testing at nearly 150 stress-prone sites in eastern and southern Africa are yielding 20 percent more, on average, than the ones they replace, and the best new varieties are doubling yields.

On the other side of the world, rice researchers have found genetic relief from floods. They have identified a rice gene that allows plants to survive when completely submerged for up to two weeks, while most rice survives underwater for only three days. The “waterproofing” trait has been transferred into a popular rice variety in Bangladesh, and is helping farmers reduce crop losses from flooding.

Among the world’s most naturally hardy food crops are barley, millet and sorghum, which are widely grown in dry climates. Barley breeders in Syria have demonstrated how drought tolerance in this crop can be markedly improved through a method involving farmer participation, and the approach is now being applied in many other countries of the Middle East and North Africa. Using tools from molecular biology, researchers have isolated and are employing the so-called stay-green trait in millet and sorghum to bolster their drought tolerance.

Researchers are also looking to bolster livestock breeds and their food sources, and are currently introducing data on the distribution of African livestock breeds into computer-based geographical information systems, or GIS. When overlaid with climate change and ecological data, this information will help select breeds for environments where drought is becoming more prevalent. Additionally, to secure food sources for livestock, researchers are selecting and promoting drought-tolerant grass and legume species.

Apart from causing direct damage to crops and livestock, higher temperatures and related changes will expose them to further depredations of diseases and pests, which already take a heavy toll on developing-country agriculture. To anticipate and prepare for this problem, CGIAR scientists are examining the likely effects of climate change on major biotic stresses in agriculture, including certain human and animal diseases such as malaria and trypanosomiasis.

Changing the System

The performance of crops and livestock under stress obviously depends not just on their inherent genetic capacity but on the whole system in which they are produced. For that reason, any serious effort to increase the resilience of developing-country agriculture in the face of climate change must involve more prudent management of crops, animals and the natural resources that sustain their production while providing other vital services for people and the environment. Water is an especially critical resource, and its management is closely intertwined with that of soil and biodiversity, including forests.

Research in improving the management of natural resources in developing countries is generating new knowledge and tools that are highly pertinent to the task of helping farmers cope with changing climatic conditions. For example, a recently completed “comprehensive assessment” of water management over the past 50 years points to a wide range of proven technologies, such as water harvesting and simple irrigation systems, as well as policy options for increasing water productivity in both irrigated and rainfed agricultural systems, including livestock and fisheries.

Similarly, international networks of tropical soil scientists — such as the African Network for Soil Biology and Fertility — have devised integrated approaches to improving soil fertility that combine targeted application of inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers with the use of livestock manure and other locally available organic sources of nutrients.

One such nutrient source consists of various “agroforestry” species — especially of the genera Gliricidia, Sesbania and Tephrosia — that thousands of farmers in southern Africa have adopted to raise soil fertility on fallow land. Agroforestry is the practice of integrating “working” trees into agricultural landscapes as natural vegetation is cleared. In addition to maintaining soil health through nitrogen fixation and use of cuttings as fertilizer and mulch, these trees provide useful products, such as animal fodder, fruit, timber, fuel, medicines and resins.

CGIAR forestry research has produced a rich collection of knowledge and tools that provide conservationists and others with better means of monitoring forest management and certifying whether it is sustainable in particular cases. Of the total forest area certified so far, more than 80 percent (some 37 million hectares) has been certified by companies that acknowledge using the products of this research. This has resulted in better forest management, contributing to more sustainable livelihoods for forest dwellers.

With the knowledge and technology already available, large improvements can be made in natural resource management. These are already imperative and will become more so in the coming decades both to help mitigate climate change — that is, reduce greenhouse gas emissions through increased capture of carbon in trees, agroforestry species and crop residues left on the ground — and to better enable farmers to cope with climate change. Without help, developing-country farmers will stand little chance of success.

Markets and Models

As compelling as this logic may be, fostering widespread use of knowledge and practices aimed at protecting natural resources is not easy, though it is being accomplished. Three conditions must be met to accelerate the process: strong incentives, able institutions and supportive policies.

Researchers are exploring avenues that enable the rural poor to afford investing in improved management of natural resources. A central challenge is to link rural communities more strongly with markets for higher value products and services, such as horticultural crops, tropical fruits, livestock products, ecotourism and a variety of environmental services.

|

| Widespread adoption of agroforestry species in southern and eastern Africa has the potential to boost removal of carbon from the atmosphere, in addition to other benefits, such as improving soil fertility in maize and other food crops. Photograph is by the World Agroforestry Centre. |

One promising option involves the new and rapidly growing world market for certified reduction of carbon emissions. Under the Clean Development Mechanism established by the Kyoto Protocol, countries that do not meet their agreed targets in emission reductions can buy the service from other countries. Carbon funds have been established for this purpose, but so far they have traded mainly with sectors such as energy and transportation in developed countries.

Some schemes, however, such as the BioCarbon Fund, have been set up that cater specifically to agricultural and forestry projects. But limits on payments to such projects and the complexity of the procedures pose significant barriers to participation, especially for small farmers.

Exciting work is under way on various fronts to reduce the obstacles to carbon trading. For example, CGIAR agroforestry researchers have devised and are applying a new technique in eastern Africa that assesses soil conditions, including carbon stocks, with a high degree of accuracy. Involving the use of satellite imagery and infrared spectroscopy, the technique is much cheaper than on-the-ground verification.

Scientists are also developing simulation models that will enable them to provide comprehensive assessments of the many factors affecting food security, poverty and the environment as influenced by climate change. Such information is critical for enabling policymakers and others to define a vision of the way forward toward sustainable development and to design measures that will help realize that vision.

This vision must include new institutional arrangements at the local, national and international levels that will facilitate the participation of small farmers and other land users in carbon trading.

Let’s Be Civilized

Developing-country agriculture is one of the central arenas in which the threat posed by climate change must be confronted. The efforts under way so far provide part of the basis for action, but they must be more sharply focused and better coordinated.

Much depends on the success of collaboration. Agriculture, after all, still forms the basis of “civilization,” a concept that has less to do with material and cultural progress, according to world-renowned historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto, than with how people shape and adapt to diverse environments in meeting their food and other needs.

Global climate change poses a new challenge to humanity’s skill at maintaining viable livelihoods under highly diverse and variable climatic and environmental conditions. We might even think of it as the ultimate test of just how civilized we can be.

Last month, construction began on what’s being called the Noah’s Ark of seeds, or the Doomsday Vault. The Svalbard International Seed Vault is a “fail-safe” vault that will hold seed samples of most food crops from most countries. It is designed to protect the essential agricultural seeds from damage or loss due to climate change, war or any other disaster, according to the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) Global Crop Diversity Trust, which is co-funding the project with the Norwegian government. The vault is being carved 120 meters deep into an island not far from the North Pole. Researchers chose the site partly because the ground is perpetually frozen (permafrost), thus providing natural refrigeration for the seeds, and partly because at 130 meters above sea level, the site is high enough not to be affected by even the most drastic rising seas should all polar ice melt. Deep inside the island, the seeds will be kept at a cool 10 to 20 degrees Celsius below zero, so even if air temperatures rise significantly and much permafrost melts, the site should be secure, according to researchers involved in the project. About 1,400 seed banks, or genebanks as they are often called, exist worldwide, ranging in size from one type of seed to more than 464,000 different samples in the U.S. genebank, according to FAO. Exactly how many and what type of seeds will be in the Svalbard vault is ultimately up to each country that sends in its seeds. The vault is capable of holding up to 3 million seed samples, which would make it the most comprehensive in the world. Seed banks are important for preserving biodiversity and genetic variation, researchers say. Different types of crops have different genetic characteristics, which may make one variety resistant to disease and another resistant to drought. For example, more than 100,000 varieties of rice exist, each with varying genetic traits. Still, a large number of crop varieties are thought to have already been lost through history, according to FAO. For example, of the 7,100 named apple varieties grown in the United States in the 1800s, more than 6,800 no longer exist. “Every day that passes we lose crop biodiversity,” said Cary Fowler, executive director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust in a Feb. 9 press release. “We must conserve the seeds that will allow agriculture to adapt to challenges such as climate change and crop disease,” he said. The vault, which is scheduled to be finished in September, is part of a larger global strategy being implemented by the Diversity Trust to protect collections of crop genetic diversity from the ravages of natural disasters, rising temperatures, rising sea levels, floods, drought, and disease, as well as from human-induced issues such as wars, civil strife and accidents. |

Links:

Consultative

Group on International Agricultural Research

Svalbard

International Seed Vault

Global

Crop Diversity Trust

U.N.

Food and Agricultural Organization

Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change

Subscribe

Subscribe