|

FEATURE

Marine Protected Areas Help Safeguard Aquatic Life

Jane Lubchenco and Kirsten Grorud-Colvert

|

| Ochre seastars congregate in the Oregon intertidal zone. Photograph is by Jane Lubchenco. |

There was a time when the entire ocean was a de facto marine protected area. The number of animals taken from the ocean was limited by geography and a lack of technology. Certain parts of the ocean were off limits, not because their boundaries were enforced, but because they were unreachable by coastal people venturing out in wind-driven or human-powered boats. These fishermen caught only a few types of animals and only at shallow depths.

With the invention of trawl nets, engine-powered boats and on-board freezing capabilities, the range and depth of fishing increased. Those early catches are dwarfed by what we catch today. Over time, fishing has become even more efficient and more technologically savvy. With the addition of sonar and high-tech fish-finders, fishermen are now able to precisely target massive schools of fish. Modern day freezing capabilities mean that ships can go out farther and stay out longer. These advances have created the potential for unsustainable harvesting rates.

Fishing at unsustainable levels has already had consequences: According to the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization, at least one-third of global fisheries are overfished. Biodiversity has also decreased in many systems, most likely as a result of overfishing. This loss of biodiversity can lead to changes in ecosystem stability, water quality and time to recover after a disaster.

Although many ocean ecosystems are currently disrupted, scientific evidence suggests it’s not too late to take serious measures to protect the marine ecosystem around us. Marine science can help us find potential solutions for the future.

|

| Studies have shown that marine creatures such as these coral reef fish in the Florida Keys are more abundant and grow bigger in marine reserves than outside the reserves. Photograph is by Evan D’Alessandro. |

Marine Protected Areas

Marine resources have continued to decline despite traditional management based on size and harvest limits. Moreover, fishing often affects non-target species that are caught in nets and traps but not used for food, including inedible invertebrates, smaller herbivorous fish, sea birds, marine mammals and sea turtles. Destructive fishing gear degrades habitats such as coral reefs and other areas of the seafloor with fragile communities. These non-target species and delicate habitats are not well protected by traditional management. To address changing needs for protection, area-based management has risen to the forefront as a new tool for stemming the tide of ecosystem degradation. Marine protected areas (MPAs) are one type of area-based management that is showing promise and garnering attention.

The World Conservation Union defines an MPA as “any area of intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed environment.” The three main goals of MPAs are to maintain essential ecological support systems in the oceans, to ensure the sustainable use of marine species and ecosystems, and to preserve biodiversity.

MPAs are set aside for the specific purpose of marine conservation, but they may achieve this goal using different protection levels. Some MPAs allow fishing only in specific areas, while others permit fishing for non-target species throughout their borders. Other MPAs allow all fishing but prevent other activities, such as oil drilling. MPAs may be zoned for multiple uses, including no-take areas, regions managed for recreational or commercial fishing, or sites set aside specifically for tourism.

For example, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia covers 344,400 square kilometers and is zoned into seven different protection levels. These include “Marine National Park” zones where only tourism is permitted, “Preservation” zones where only limited-impact research can occur, and “Conservation Park” areas where certain types of fishing are allowed. The 20-square-kilometer Mimiwhangata Marine Park in New Zealand is also a marine park, but it has only one protection level. In Mimiwhangata, commercial fishing is prohibited but recreational fishing is allowed. Both of these parks fall under the broad category of an MPA.

MPAs can also take the form of temporary closures, such as on Georges Bank off the New England coast. Such temporary protected areas have been noted to have positive impacts on seafloor-dwelling creatures. Located along the southeastern boundary of the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank was a historically rich fishing ground for many commercially important species, including scallops, cod and haddock. After catches declined in the early 1990s, three large areas totaling 16,835 square kilometers were set aside from all fishing except lobster trapping. Data from Steve Murawski of NOAA and his colleagues showed that within four years, scallops were larger and 14 times more abundant in the closures than in surrounding areas. Almost a decade later, fishing has increased around the closed-area boundaries, likely due to the observed increases in the number of haddock within and outside the closures.

Marine reserves are a special type of MPA where all forms of extraction — including plant, animal and mineral resources — or destruction are prohibited. They are a unique management tool because they protect all the species in a specific area and prevent destruction of their habitat from damaging fishing practices. Marine reserves are sometimes called ecological reserves, no-take areas, harvest refugia or marine life reserves. Because there are many different names for this type of protection, the total number of marine reserves globally is unknown. Current estimates indicate that marine reserves cover less than 0.01 percent of the world’s ocean.

In 1998, a group of international scientists formed a working group at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis to develop better scientific understanding of the role of MPAs and marine reserves. Following this process, in 2001 more than 160 scientists signed a consensus statement that marine reserves are a highly effective but under-appreciated and under-utilized tool for management of marine ecosystems.

The benefits of marine reserves

Scientific evidence collected from marine reserves over the last few decades and published in peer-reviewed journals demonstrates that marine reserves can impact communities both inside and outside their borders.

|

| A diver takes a census of coral reef fish in the Florida Keys. Photograph is by Evan D’Alessandro. |

Protection inside marine reserves can lead to long-lasting and often rapid recovery of species density, biomass, reproductive potential and diversity. A new analysis of 125 fully protected no-take marine reserves from 29 countries indicates that the majority of ecosystem responses to full protection are positive. On average, biomass within marine reserves was six times higher and density was three times higher in reserves than in non-reserve areas. Both organism size and species diversity were approximately 1.3 times higher in marine reserves relative to control areas. Positive effects occurred in both tropical and temperate regions.

As larger fish and invertebrates produce more young than smaller ones, larger organism sizes in marine reserves lead to the added benefit of increased reproductive potential. For example, a 40-centimeter-long bocaccio rockfish produces an average of over 200,000 eggs per year, whereas an 80-centimeter-long fish, at double the length, produces nearly 10 times as many eggs.

Although implementation of marine reserves can lead to rapid increases in density or biomass within their borders, full recovery of the protected systems can still take much longer. Some of the best examples of ecosystem response rates in marine reserves come from the Philippines, Kenya and New Zealand, where marine reserves have been protected for multiple decades, providing a unique opportunity to assess how long it takes a community to recover when it is fully protected.

Recent work by Tim McClanahan of the Wildlife Conservation Society and Nick Graham from the University of Newcastle demonstrates that fish assemblages in Kenyan marine reserves can take more than two decades to reach stable levels. Using similar data from two marine reserves in the Philippines, Garry Russ of James Cook University and Angel Alcala of Silliman University showed that response time may even vary between sites. Fish communities in one Filipino reserve would likely need 15 years to recover fully, while a nearby reserve required a minimum of 40 years of protection to completely restore the community.

Different rates of response among sites can result from variations in species groups, initial numbers or sizes of individuals, types of habitats protected, or level of exploitation prior to reserve implementation. One common denominator among reserves is that full recovery of a community does not happen overnight, although there is often a dramatic initial response to protection.

Benefits may also occur outside reserves, although these impacts are more difficult to assess. Movement of adults across protected area boundaries or seeding of larvae as they are spawned and exported from the reserve can lead to linkages among sites.

As numbers of fish or mobile invertebrates in MPAs and reserves increase, spillover of adults or juveniles across reserve boundaries is more likely to occur. Evidence of spillover and its positive effect on nearby fisheries has been demonstrated in Florida and St. Lucia, the Philippines, Kenya, Australia, New Zealand, the Western Mediterranean and on Georges Bank. Many fishermen have modified their fishing patterns to target higher densities of fish along MPA borders.

|

| A graduate student collects mussel tissue samples in the Oregon intertidal zone to determine how temperature stress affects reproduction. Photograph is by Jane Lubchenco. |

Larval export is more difficult to quantify, as young marine organisms have the potential to travel long distances via ocean currents. Using the amount of time larvae spend in the plankton before settling to suitable habitats together with models of the observed ocean current patterns, scientists can predict which areas are connected by larval dispersal. Larval genetics provide additional information about where larvae might have come from and how much exchange occurs among groups of organisms at different sites. Estimates of the number of larvae traveling to suitable areas outside MPAs, however, have yet to be determined for specific areas.

Most larvae travel distances much greater than those covered by juveniles and adults. Thus most reserves will be smaller than the range of larval dispersal. Scientists are now trying to find mechanisms to protect multiple life stages as well as the majority of species within a marine reserve. Networks of small, connected marine reserves are showing great promise for protecting species during different portions of their life.

Networks of marine reserves can provide links much like stepping stones among sites if single reserves are spaced at distances comparable to larval dispersal ranges. Networks have the added benefit of preserving larger populations that are less likely to be wiped out by unpredictable catastrophes than smaller populations in individual reserves. Since climate change would lead to shifts in these species’ ranges, reserve networks that extend across latitudes are better able to protect the shifting range of species than solitary reserves.

The human dimension of MPAs

According to the online resource MPA Global, at least 4,500 MPAs exist worldwide and cover some 2.2 million square kilometers — 0.6 percent of Earth’s oceans. Simple designation of an MPA, however, does not necessarily reflect the level of protection in the field. Parks that are designated on paper but not implemented or enforced (often called “paper parks”) yield little benefit.

MPAs may not work if they are inadequately enforced or are unsupported by the surrounding communities that depend on the protected resources. For example, Russ and his colleagues identified low enforcement rates and illegal fishing in no-take areas of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, even though the sites they monitored were near populated coastal areas and within one of the largest and best-staffed MPAs in the world. Enforcement and popular support remain major challenges.

|

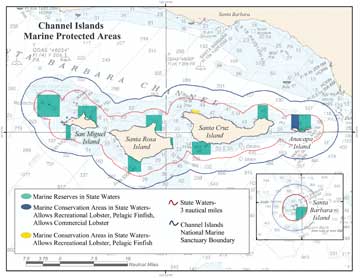

| The Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of California consists of three different types of protected areas: marine reserves, from which no plant, animal or mineral resources can be removed; marine conservation areas, from which certain species can be extracted recreationally; and marine conservation areas, from which certain species can be harvested both commercially and recreationally, but other species are off-limits. Image is courtesy of the California Department of Fish and Game. |

Establishing MPAs tends to create an understandable level of concern among fishermen and other resource users whose livelihood depends on fishing at these sites. Even if they stand to benefit in the long term from enhanced fishery resources outside (but as a result of) the reserve, however, fishermen may be faced with short-term loss of revenues, thus setting up the challenge. In areas where marine reserves have been in place for many years, fishermen are often strong supporters because they have seen real benefits.

Involving locals in the design of MPAs is widely endorsed for multiple reasons. Fishermen and resource users’ traditional ecological knowledge can provide vital information, such as species movement patterns and seasonal levels of abundance in certain areas. These local users may be the first to identify decreases in stocks or destruction of habitats. They may have an important sense of which sites would benefit the most from protection in an MPA.

When users’ input is unsolicited or disregarded in the MPA planning process, however, noncompliance can result. In an analysis of a range of case studies, Carolyn Lundquist of New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and Elise Granek of Oregon State University found that one of the most important characteristics for success in a marine conservation effort was involving stakeholders in all phases of the process.

The future of MPAs

MPAs, including marine reserves, are just one type of tool, albeit a powerful one, for protecting marine biodiversity and conserving populations. MPAs alone, however, will not bring about the large-scale, long-term changes required to restore and maintain the functioning of marine ecosystems. Additional drivers of disruption must also be addressed, such as run-off and atmospheric deposition of nutrients and chemical pollutants, alteration of coastal habitats such as wetlands and estuaries, alteration of flows of water and sediments to coastal areas, deposition of marine debris and global climate change.

When coupled with the proper management of outside factors, MPAs may not only protect stocks but also habitat and its associated diversity, improving the productivity and resilience of our ecosystems. Area-based management is one good way to move forward — it’s not too late to stem the tide of changes in our ocean.

Links:

National

Marine Protected Areas Center

Lubchenco/Menge

Lab at Oregon State University

California

Department of Fish and Game

World

Commission on Protected Areas

Subscribe

Subscribe