|

FEATURE

Changing the World One Kilowatt at a Time

Megan Sever

Fortune 500s going green Print Exclusive

Source: Energy Information Administration |

“It’s unrealistic to expect that everyone’s going to stop traveling all of a sudden or stop using electricity. Technology is what I think is the answer.”

With those words, Sergey Brin, one of the co-founders of Google, Inc., announced last November what might be the prolific corporation’s most ambitious endeavor yet: to help slow down the rate of climate change. Google’s top executives — Brin, fellow co-founder Larry Page and Chairman and CEO Eric Schmidt — have arguably already changed the world through search engines and mapping programs. Now, they plan to apply their vision and innovation to the electricity market. The goal? To create renewable energy that’s cheaper than coal. And to do it in less than a decade.

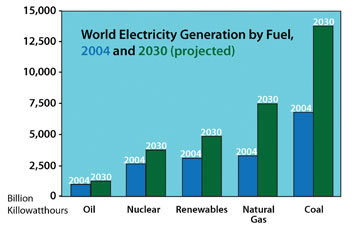

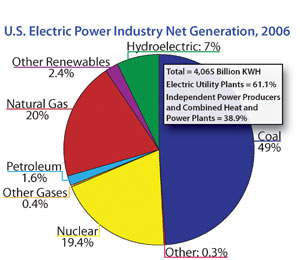

Continuing call for coal

Coal is the cheapest and most abundant source of energy for electricity in the world, generating more than 40 percent of all electricity globally, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). In the United States, that number is almost 50 percent — and that percentage is not predicted to decrease anytime soon. In fact, by 2030, EIA estimates that coal may actually increase to 55 percent of the U.S. electricity generation and 45 percent of global electricity generation. Between now and 2030, global primary energy demand will increase by more than 50 percent, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates, with more than 70 percent of this increase coming from developing countries, particularly China and India. And coal has been meeting the recent global energy demand surge, according to IEA.

Philip Rickerby |

| Google is investigating three renewable energies, including geothermal, as shown here in New Zealand. Instead of traditional geothermal, the company is looking into enhanced geothermal. |

Coal, however, is not “clean” or “green” — a black mark in a world growing more concerned about greenhouse gas emissions. Coal use accounts for at least 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and 27 percent of U.S. emissions — in fact, the United States alone produces nearly 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year from coal-burning power plants. But coal is so abundant and so much cheaper than natural gas or any form of renewable energy that even when coal-fired power plants are retrofitted to burn cleaner, the fuel is still more cost-effective.

For electricity generation, coal is now cheaper than natural gas, once the cheapest energy source. Electricity produced from coal-fired power plants runs anywhere from 2 to 4 cents per kilowatt hour. Electricity produced from natural gas varies from 3 cents per kilowatt hour up to 12 or more cents per kilowatt hour, depending on the market prices for natural gas. Electricity produced from renewable sources tends to be more expensive, in part because the capital costs for new power plants based on renewable fuels remains higher than new coal-fired power plants. Wind power averages about 5 cents per kilowatt hour, according to the American Wind Energy Association, making it close to coal, but there are technical issues to be resolved. Solar power from photovoltaic solar cells is even more expensive, averaging 10 to 40 cents per kilowatt hour, depending on whether it is generated at a solar power plant or on a house or small building. Geothermal averages about 5 cents per kilowatt hour, but it requires the right local geology. “We think we need to get in the range of 1 to 3 cents per kilowatt hour for solar or other renewables to be really competitive with coal,” says Bill Weihl, Google’s “green energy czar.” And Google plans to do it “in years, not decades,” he says.

Reducing the footprint

EIA projects that global electricity generation from hydroelectric and other renewable energy resources will increase at an average annual rate of 1.7 percent through 2030. But continuing high oil and natural gas prices, government incentives to increase the use of renewables and improved technologies may push that number higher. That is where Google comes in.

Source: Energy Information Administration |

In November, Google launched an initiative called RE<C: Renewable Energy cheaper than Coal. The goal is two-fold: “to reduce our own footprint and to find ways to do that that will not just help us with our footprint but that will also help the rest of the world,” Weihl says. The scale of the problem is enormous, he says, and many changes are going to be needed to reduce the effects of climate change. The primary step, he says, is “making renewable, clean, non-emitting energy sources cheaper than the polluting alternatives.” And there are two ways to do that: “Make the polluting ones more expensive … or make the clean ones a whole lot cheaper.” Some combination of the two is almost certainly going to be needed, he says.

“To deal with climate change, you really have to tackle the big problems, which are in electricity generation … and transportation fuels,” Brin said at the Nov. 27, 2007, initiative rollout press conference. Google is starting with electricity. “[We] need to have clean technologies that are ready to start to scale up” and that will cost less than coal within 10 years, Weihl says. Although there are lots of great technologies out there, and lots of companies are doing “exciting” things, he says, “many people are really worried that we’re not doing enough, we’re not going to get there fast enough” to mitigate the effects of climate change. Google wants to find renewable energy that can be cheaper than coal in as few as five or six years, he says. “It might be a little less, might be a little more; [but] we don’t want the target and the likely outcome to be 10 or 15 or 20 years.”

| This coal-fired plant in California’s Mojave Desert produces power for the neighboring mines and industries. Google is investing in technologies that instead harness the sun’s power in places such as the Mojave. |

One key point is that these technologies need to be “scalable” — meaning they need to be able to be usable by a large number of consumers quickly. After talking to a lot of researchers, venture capitalists, government labs and academics, Google settled on three technologies — solar thermal, high-altitude wind and enhanced geothermal powers — that it thinks can be scaled up quickly, and that have the potential to produce a gigawatt of electricity in just a few years (one gigawatt could power a city the size of San Francisco). The corporation is now hiring new people, investing tens of millions of dollars in internal research and development and investing in a couple of companies that are already working on these technologies to help them develop more quickly.

Renewables’ price is right

Solar thermal has been used for at least a couple of decades but has been picking up steam recently. A more well-known form of solar energy uses photovoltaic solar panels that convert sunlight directly into electricity. But even though prices of solar panels have fallen 50 percent per decade, the technology is still expensive, Weihl says.

Solar thermal — which uses mirrors or a similar mechanism to focus sunlight onto a receiver that captures the energy as heat and then uses that heat to generate steam to run a turbine to generate electricity — is a highly scalable energy because the materials used to create solar thermal energy “are nowhere near as exotic as the photovoltaic system,” Weihl says. Unlike photovoltaic solar panels, solar thermal is not a system that would be mounted on an individual building. “You would deploy [the system] on much larger scale, where tens of megawatts or hundreds of megawatts are needed,” he says. And the price is right: Whereas electricity from photovoltaics often runs 25 to 35 cents per kilowatt hour, solar thermal will run less than half of that, Weihl says. With only minor adjustments — such as decreasing the amount of onsite construction — it could easily cost as little as 7 cents per kilowatt hour in the not too distant future, he adds. Google is investing money in a California-based company called eSolar Inc. that is working on solar thermal, as well as conducting its own internal research and development on the technology.

|

| Last year, Google installed 9,212 solar panels at its Mountain View, Calif., headquarters, providing up to 30 percent of the company's peak demand for electricity. |

With high-altitude wind power, Google is investing in outside research and development, primarily through a California-based company called Makani Power Inc. High-altitude wind technologies generally use either something like a giant sail to capture winds several kilometers up in the atmosphere, where average winds are about 10 times as strong as they are at the height of the average land-based wind turbine, or they use helicopter-like flying turbines that send power back to Earth through tethers. Makani is not divulging their technology, but the company says of all renewables, high-altitude wind produces the largest amount of energy per square foot, and that capturing even a small fraction of the global high-altitude wind energy flux could be sufficient to fulfill the world’s energy needs.

Google is also looking at enhanced, or engineered, geothermal energy, but is less certain about how to scale up that technology, Weihl says. Traditional geothermal involves drilling down into an underground hot water reservoir — usually in a volcanic region — and then pumping up the water and using it to generate power. To be practical, this requires having the right kind of geological formation with a water reservoir that’s close enough to the ground surface. Enhanced geothermal, however, can be used just about anywhere. The idea behind enhanced geothermal systems is that there’s enough heat to generate electricity anywhere on Earth — if you drill deep enough. So rather than looking for existing water reservoirs, companies can just look for heat. Even if there are no water reservoirs in hot areas, they can pump water into fractures in the rock, where the water heats up and can be pumped back out to generate geothermal power. “There was a major study on this released by MIT last year that indicates that there’s a lot of promise in that sort of technique,” Weihl says. Enhanced geothermal “has the potential to provide baseline power with a very high capacity factor and the potential to be usable in many, many places around the world. Not everywhere, but many more places than traditional geothermal,” he says.

“We’re looking at companies that have promised to develop technologies that will get us there more quickly,” Weihl says. “The feeling is that if we’re successful, there’s money to be made there.”

A Good Business Decision?

Google’s new venture into electricity is not just about creating energy for its own operations — although that alone would be a good business decision, said Larry Brilliant, executive director of Google.org, Google’s philanthropic arm, which is funding the initial investments. “But it’s an even greater social benefit if we can simultaneously help create a technology pathway that allows everyone in the developed and developing worlds [access] to power that does not contribute to climate change,” Brilliant said.

Google already supports its own energy usage through solar energy and efficiency measures. In 2007, it installed solar panels at its headquarters in Mountain View, Calif., which now provide 1.6 megawatts of electricity. At peak demand, that fulfills about 30 percent of Google’s power usage at the site, Weihl says. And the company has taken other steps to reduce its footprint as well, such as having automatic lights that shut off when people aren’t around, installing new, more energy efficient heating and cooling units and buying enough carbon credits to make the company carbon neutral in 2007. The company is also a founding member of the Climate Savers Computing Initiative, partnering with Intel and other major companies to make computers more efficient.

But Google decided to take things a step further. Part of the company’s overall operations plan is to invest in newer ideas that may be somewhat outside the typical purview of Google’s operations. If things go according to plan, Google may not only change the world by furthering renewable technologies, but the company also stands to make a lot of money. “But before we talk about the profits, we need to develop the technologies,” Weihl says.

Weihl says he hopes that other companies, and especially the government, will follow suit and begin to invest more in renewables. “I do think capitalism works pretty well to drive investments … probably the quickest way to really avert the climate issues that we face is to have a profit-driven, healthy business ecosystem that drives a lot of investments,” said Larry Page, co-founder and president of products at Google, at the rollout. Only time will tell if that is the case.

Links:

U.S. Energy Information Administration

Google's RE<C (Renewable Energy Cheaper Than Coal) program

Earth Science World Image Bank

eSolar Inc.

Makani Power Inc.

Google Foundation

Climate Savers Computing Initiative

Subscribe

Subscribe