|

NEWS NOTES

Fourth quarter in the Arctic

National Snow and Ice Data Center |

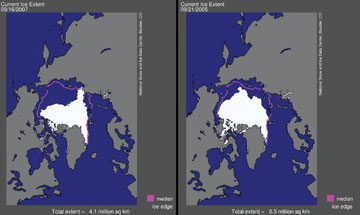

| At left is the Arctic sea-ice cover in September 2007, which hit an all-time low. At right is the sea-ice cover in September 2005, the previous record low. |

That the Arctic is warming may be old news. That summer 2007 was the warmest on record, with the least amount of sea-ice cover, probably doesn’t surprise you either. Last year’s record sea-ice melt was primarily due to two factors: warm southerly winds, which both melted ice and blew it away from the coasts; and solar heating, which increased ocean temperatures as the exposed darker ocean absorbed more heat than ice does. But something else was happening too, which surprised researchers: The Pacific Ocean is carrying more heat through Arctic seas into the Arctic Ocean, potentially peeling back the ice at the surface as warmer waters lap at the edges of the ice.

In summer 2007, Arctic sea ice fell to the lowest levels since satellite measurements began in 1979. In September 1980, summer sea ice covered an area roughly the size of the continental United States, said Don Perovich, a geophysicist at the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory in Hanover, N.H., at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, Calif., in December. By the end of the summer 2007 melt season, the average sea ice extent was nearly half what it was in 1980, and 23 percent lower than in 2005, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “The Northwest Passage was ice-free in September,” and the question is why the melting is progressing so quickly, Perovich said.

Average sea-surface temperatures in the Arctic Ocean were 3.5 degrees Celsius warmer in summer 2007 than the historical average, and 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than the previous historical high, said Michael Steele, a polar researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle, and his colleagues at the meeting. The problem is, Steele says, that warming not only melts summer sea ice, but it also reduces the amount of fall ice growth by up to a meter.

The reasons the melt was so extreme in 2007 are manifold: Warmer air temperatures play a role, as do winds, clouds, the ice-albedo feedback (water is darker than ice, so it absorbs heat from the sun instead of reflecting it, thus warming the surface more) and increased solar heating of the ocean and atmosphere, Perovich said. The winds and solar heating were the primary causes in 2007, Steele says. But there’s another factor that needs to be examined, he says. The ocean is transporting heat — and that may be both a cause of, and a response to, warmer sea-surface temperatures.

The 2007 melt was particularly severe north of the Bering Sea, Steele says. Water coming into the Arctic Ocean from the Pacific through the Chukchi and Bering seas was definitely warmer, he says. This year, because there was more open water due to the other causes of sea-ice melt, and overall thinner, more easily-melted ice, “the heat went a little farther,” he says.

Steele says he doesn’t know why exactly the ocean currents coming through the Chukchi and Bering seas are warmer. Nor can he say whether or not the entire Pacific is warming significantly, or if some parts are warming more than others.

“We know the ice retreated and the ocean warmed this year,” Steele says. “But we don’t know whether it was just a contribution or a causation”; however, model simulations strongly indicate that the ocean warmed mostly because the ice retreated and thus the sun was able to warm the ocean surface: The ocean warming was more of a response to sea ice retreat than a cause of it, he says.

Another unanswered question, Steele says, is how much of the warming is a result of climate change versus natural variability. For example, researchers know that when the winds change in the Arctic Oscillation — a pattern of winds that affects the Pacific and Arctic ocean circulation gyres — the gyres change. From 1930 to 1965, Arctic seas were cooler than average. The oscillation changed around 1965, and from then through 1995, sea-surface temperatures were slightly above average, Steele and colleagues wrote in Geophysical Research Letters, Jan. 29. The team did see a pronounced change since 1995 in sea-surface temperatures, however, which they say cannot be attributed solely to changes in the oscillation. “So we’re trying to tease out natural variability” from the data and models, he says. There’s a lot more work to be done, he adds.

In the meantime, what the Arctic needs to get back on track is a couple of really cold winters, Perovich said. Sea ice could make a pretty quick and strong comeback if that were to happen — but at present, the thickness and extent of summer sea ice is a major concern, especially for the animals and people who live in the Arctic and depend on sea ice for hunting and food sources. “And as you go further down this path, it gets harder to come back,” he said. “It’s the fourth quarter, and we’re down two touchdowns.”

Subscribe

Subscribe