|

Web Extra Wednesday, August 1, 2007

Cold wars: Russia claims Arctic land

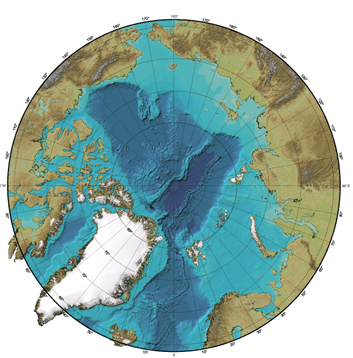

IBCAO-NOAA-NGDC |

| The underwater Lomonosov Ridge stretches across the floor of the Arctic Ocean between Greenland and Russia, crossing through the geographic North Pole. Russia recently claimed that the ridge is an extension of its continental shelf, in a bid to expand its territory to include a large swath of the potentially oil- and gas-rich Arctic seafloor. |

The largest country in the world has ambitions to expand. New evidence from Russian scientists suggests that the North Pole is in an extension of the country’s continental shelf, president Vladimir Putin announced in June. He claims that a large chunk of the Arctic Ocean, including the North Pole, rightfully belongs to Russia. That claim would also include an estimated 10 billion metric tons of hydrocarbons buried under the Arctic seafloor.

Arctic waters have long been in dispute, not least because of the valuable deposits of oil and natural gas that lie below the ice-covered ocean. The region around the North Pole, however, has been considered international territory since 1997, when the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea was ratified by 152 nations including Russia (although the law has not been fully ratified by the United States). The law limited the control of the five countries bordering the Arctic — Russia, the United States, Canada, Norway and Denmark — to economic zones extending to about 320 kilometers from their coasts. None of these zones currently reaches as far as the North Pole. The law allows, however, that a country can extend its economic zone if it can prove that the Arctic seafloor’s underwater ridges are not a separate feature, but a geological extension of the country’s own continental shelf.

Russia’s claim, which would extend its control over an additional 1.2 million square kilometers of the Arctic, hinges on new evidence by a team of Russian scientists that recently returned from a 45-day polar expedition. The team said they have new acoustic scans of the seafloor that show that Russia’s northern Arctic region is directly connected to the North Pole by an underwater ridge called the Lomonosov Ridge, Russian newspaper Komsomolkaya Pravda reported on June 27. Russia has attempted to expand its Arctic territory before, but that claim was rejected by the U.N. Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in 2002. By law, Russia could either accept the new limits, which would then be binding, or gather additional data and submit a revised submission, which it chose to do. Their new evidence, Russian scientists said, would greatly strengthen Russia’s revised case, which it intends to put before the commission when it next meets in 2009.

The Law of the Sea defines the outer limits of a country’s shelf as the “natural” extension of the land mass either to the outer edge of the continental margin or to 320 kilometers from the coast. Whether the Lomonosov Ridge can be considered a geological extension of the Siberian shelf is unclear, however. “It becomes a matter of definition,” says Jim Cochran, a marine geophysicist at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y. The ridge is a narrow band of continental crust stretching between Greenland and Siberia — and passing through the geographic North Pole — that rises above deep ocean basins on either side, and runs parallel to the nearby Gakkel Ridge, a mid-ocean ridge spreading center.

The Lomonosov Ridge’s complicated history adds to the scientific uncertainty. In the early Tertiary (50 million years ago) the ridge was ripped away from the outer part of the continental margin of Eurasia, north of Scandinavia and Russia, and a new ocean basin formed between the ridge and the shelf, Cochran says. On the Alaskan side, the basin between the ridge and the shelf is older, dating to the Cretaceous period (120 million years ago), he says.

At question is exactly how the Lomonosov Ridge and the Gakkel Ridge intersect with the Siberian part of the shelf. A number of expeditions over the past decade have studied the structure of the ridge to try to understand that intersection. From 1995 to 1999, the Scientific Ice Expeditions (SCICEX) program, in which Cochran participated, used a Navy submarine to collect a variety of information on the geology of the Arctic. SCICEX provided a closer look at the variation in geologic structure of the Lomonosov Ridge. Other seismic work, by a team of German scientists, found that the ridge becomes deeper as it approaches Siberia, with a lot of faulting in the deeper sediments. Those faults suggest that even if the ridge is currently attached to the Siberian shelf, prior to about 10 million years ago it may not have been part of the shelf at all, or was at least partially disconnected.

Based on this data, some scientists hypothesize that the Lomonosov Ridge came from a different part of the Eurasian shelf originally, and is actually a sliver of shelf that long ago became cut off from its earlier location by faulting and rifting. The piece of shelf may then have slid for several hundred kilometers along a transform fault until it reached its current location on the Siberian shelf.

“That’s where definitions come in,” Cochran says. The question, he says, is whether a piece of land that happens to be currently alongside a country’s shelf can be considered part of that shelf. “There is probably no oceanic crust between the ridge and the Russian shelf, but if something slides along your margin, is it part of the shelf or not?”

If the disputed region does become Russian territory, the country would have exclusive access to its potentially vast stores of crude oil and natural gas. Although other countries, including Canada and Denmark, have claimed in response that the Lomonosov Ridge belongs instead to the Canadian-Greenland shelf (and scientists from these countries were also mapping the region this summer), the United States has largely stayed out of the debate, while Congress continues to deliberate over ratification of the Law of the Sea. If the law is ratified, the United States would still have to wait 10 years before attempting to annex new territory, under the law.

Although many Russian media outlets have seized upon the claim — Pravda printed a map of the North Pole under a Russian flag — some Russian scientists, including Sergey Priamikov, director of Russia’s Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute in St. Petersburg, say the claim is premature, the U.K. Guardian reported June 28. Canada could make a similar claim to the pole, Priamikov noted.

To bolster their case, a new expedition of Russian scientists set out aboard the research vessel Akademik Fyodorov and the Rossiya nuclear-powered icebreaker in July, reaching the North Pole on Aug. 1. The expedition’s leaders plan to launch two mini-submarines to conduct experiments on the seafloor under the North Pole — and to leave behind a titanium capsule containing the Russian flag.

Links:

International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean

SCICEX program

International Polar Year

Back to top

Subscribe

Subscribe