|

NEWS NOTES

Going platinum

Rudolph Botha |

| The “Big Hole,” a massive open-pit diamond mine near Kimberley, South Africa, was excavated by hand from 1886 until 1914. |

Gold, diamonds, platinum: For more than a century, South Africa’s vast underground riches have lured eager prospectors and miners to the country. In recent years, with increasing applications in industry, platinum’s luster — and price — have skyrocketed. But there may be new clues to future claims on the horizon: Scientists studying the world’s largest source of platinum have unraveled the origin of its valuable ores. Knowing how these ores formed, researchers say, could help modern-day prospectors refine their strategies to locate new sources of this rare metal.

Platinum is a member of a family of precious metals called the platinum group elements (PGEs). This group of metals — which also includes palladium, osmium, rhodium, ruthenium and iridium — has become increasingly prized in industry because they are highly resistant to heat and corrosion, have unique chemical properties and are thus useful in everything from automobile catalytic converters to microelectronics.

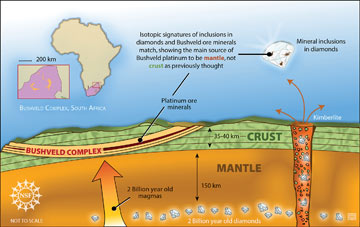

But PGEs are also exceedingly rare in Earth’s crust, with 93 percent of the world’s platinum mined in only two places: South Africa and Russia. The richest source of platinum is South Africa’s Bushveld Complex, a giant geological mix of ancient magmas that welled up into the crust more than 2 billion years ago.

To form the Bushveld ores, injections of magma reacted chemically with their original host rocks, ultimately concentrating the precious metals in layers that could be mined. But the origin of the magmas — and thus, the geological sources of the Bushveld’s unique riches — have been a source of speculation.

Previous isotopic data from the Bushveld ores had a strongly crustal “signature,” suggesting that a sizeable fraction of the platinum came from the crust rather than the mantle. Yet PGEs are much more abundant in Earth’s mantle than in its crust; furthermore, other geophysical and geochemical data also pointed to a mantle source for the magma.

“These magmas have to come from either the lithosphere or below the lithosphere,” says Steven Shirey, a geologist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington. “The question is how much of the chemical signature of the platinum ores comes from the crust and how much from beneath, in the mantle — and just where in the mantle.”

Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation |

| South Africa’s 2-billion-year-old Bushveld Complex is one of the few places in the world where platinum group elements are abundant enough to be mined. New research shows that the main source of the Bushveld platinum is mantle, not crust. |

Shirey and colleague Stephen Richardson of the University of Cape Town in South Africa decided to use another form of riches to figure out the platinum’s provenance: diamonds embedded in kimberlites, magma structures from deep in the mantle that erupted on opposite sides of the 2-billion-year-old Bushveld Complex. Although the kimberlites are younger than the Bushveld, some of the diamonds they carried to the surface are the same age as the complex. And as the diamonds formed into crystals, they incorporated tiny imperfections: pieces of the surrounding rocks. Two billion years later, the tough diamonds still contain those bits of original rock, carefully preserved.

Richardson and Shirey collected isotopic data from the inclusions within 20 diamonds mined from locations around the complex, which gave them the original compositions of those rocks. From there, they calculated that the chemical makeup of the platinum ores does indeed suggest a mantle origin, they reported June 12 in Nature. More specifically, the ores pointed to an origin in the continent’s mantle “keel” — a deep slab of mantle material attached like a boat’s keel to the base of very old continental crust.

Geological models and ideas of how ores form help exploration geologists narrow their search for mineral deposits — so the more complete the idea, the better it is for finding the ores, Shirey says. In this case, knowing that the Bushveld magma picked up the PGEs from the ancient mantle keel helps eliminate false leads — such as magma intrusions that did not pass through such keels — and focus attention on similar intrusions, he says.

“Anytime you understand the ultimate source of the element in the ore that you’re seeking, you can construct a better exploration model,” Shirey says. “Finding ores is extremely difficult, so anything you can do to cut down the number of places to look is important.”

Links:

Platinum from the deep, Geotimes online, Videocast, June 18, 2008

Subscribe

Subscribe