Natural history

The

Raging Sea: The Powerful Account of the Worst Tsunami in U.S. History,

by Dennis M. Powers. Citadel Press, 2005. ISBN 0 8065 2682 3. Softcover,

$15.95.

The

Raging Sea: The Powerful Account of the Worst Tsunami in U.S. History,

by Dennis M. Powers. Citadel Press, 2005. ISBN 0 8065 2682 3. Softcover,

$15.95.

In the blink of an eye, scenic Crescent City, Calif., was half destroyed by a tsunami that was generated by a giant earthquake thousands of kilometers away in Alaska. This account of the disaster not only records the events of that day in 1964, but also the lives of the victims and the people who became heroes. Everyone, especially those in disaster-prone regions, will be able to relate to this story of a city swamped by waves and reduced to ashes, and how it rose back up like a fiery phoenix.

Reef

Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz and the Meaning of Coral,

by David Dobbs. Pantheon Books, 2005. ISBN 0 3754 2161 0. Hardcover, $25.00.

Reef

Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz and the Meaning of Coral,

by David Dobbs. Pantheon Books, 2005. ISBN 0 3754 2161 0. Hardcover, $25.00.

Once referred to as natural philosophy, “science” was not even a term used by Charles Darwin or Louis Agassiz. Locked in a debate between the observable phenomena that Darwin termed “natural selection” and Agassiz’s belief that life on Earth was originally created as we see it today, these two men changed the very concept of scientific thought during the 19th century. Agassiz’s son Alexander, although he agreed with natural selection, also became mired in a debate with Darwin over the origins of coral. To disprove Darwin, he traveled the seas and set the stage for modern oceanography. Anyone with an interest in the history of science will find this an enlightening look at the development of modern paleontology and oceanography.

Genesis:

The Scientific Quest for Life’s Origin, by Robert M. Hazen. Joseph

Henry Press, 2005. ISBN 0 3090 9432 1. Hardcover, $27.95.

Genesis:

The Scientific Quest for Life’s Origin, by Robert M. Hazen. Joseph

Henry Press, 2005. ISBN 0 3090 9432 1. Hardcover, $27.95.

Amid the controversy over evolution and creationism, astrobiologist Robert M. Hazen takes readers through the first steps of life’s emergence, starting from the Big Bang up to the synthesis of carbon biomolecules on the surface of Earth, in an attempt to explain the scientific quest to understand life’s origins. Hazen’s ideas on the theory of emergence — in which life began 4 billion years ago, obeying all the rules of physics and chemistry — is a journey through the modern world’s scientific advancements and perplexing questions. Because the book is a bit heavy at times in chemistry and biology, it will be most interesting to a reader with some science background.

Reading

the Rocks: The Autobiography of the Earth, by Marcia Bjornerud. Basic

Books, 2005. ISBN 0 8133 4249 X. Hardcover, $26.00.

Reading

the Rocks: The Autobiography of the Earth, by Marcia Bjornerud. Basic

Books, 2005. ISBN 0 8133 4249 X. Hardcover, $26.00.

Marcia Bjornerud tries to convey the beauty and wonder of Earth and all of the mysteries scientists attempt to unravel in her book Reading the Rocks. Bjornerud uses metaphors and anecdotes to discuss Earth’s deep history and explains the delicate balancing act that has sustained life for millions of years, but not without warning that human activities may upset that balance. The book includes a glossary and geologic timescale for reference.

Local field guides

Exploring

Stone Walls: A Field Guide to New England’s Stone Walls, by Robert

M. Thorson. Walker & Company, 2005. ISBN 0 8027 7708 2. Softcover,

$14.00.

Exploring

Stone Walls: A Field Guide to New England’s Stone Walls, by Robert

M. Thorson. Walker & Company, 2005. ISBN 0 8027 7708 2. Softcover,

$14.00.

Geologist Robert M. Thorson takes readers on a journey through New England’s stone walls, while painting a vivid historical and geological picture of the American northeast. Through Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Maine and other states, Thorson passes on the stories that each stone wall has to tell. This readable guide comes complete with lessons on how to identify a wall’s age, history and purpose. It is an intriguing story of humankind’s labors to build strong fences.

The

Street-Smart Naturalist: Field Notes From Seattle, by David B. Williams.

Westwinds Press, 2005. ISBN 1 5586 8859 5. Softcover, $14.95.

The

Street-Smart Naturalist: Field Notes From Seattle, by David B. Williams.

Westwinds Press, 2005. ISBN 1 5586 8859 5. Softcover, $14.95.

Amid the bustling city streets, David Williams, a native Seattle resident (and occasional freelance writer for Geotimes), discovers the wild, natural side of urban life. From a tiny city park to buildings composed of quarried rocks, Williams takes us to a side of Seattle rarely seen. With hand-drawn maps and personal anecdotes of Williams’ life in Washington state, The Street-Smart Naturalist introduces the reader to the geology, the eagles, the plants and even the bugs of greater Seattle. You do not have to be a geoscientist to enjoy his rambling walks through the city.

The

Geology of Southern Vancouver Island, by Chris Yorath. Harbour Publishing,

2005. ISBN 1 5501 7362 6. Softcover, $24.95.

The

Geology of Southern Vancouver Island, by Chris Yorath. Harbour Publishing,

2005. ISBN 1 5501 7362 6. Softcover, $24.95.

From volcanic cliffs to the remains of ancient landslides, Chris Yorath takes readers for a geology tour of Southern Vancouver Island in western Canada. He follows millions of years of natural processes that formed the unique landscape of this island, including plate tectonics, geomorphology and glaciology. Yorath follows a path through Cowichan Valley to the Nanoose Peninsula, and even to the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, making this a useful field guide for the region.

High

Plains of Northeastern New Mexico: A Guide to Geology and Culture,

by William R. Muehlberger, Sally J. Muehlberger and L. Greer Price. New

Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, 2005. ISBN 1 8839 0520

6. Softcover, $14.95.

High

Plains of Northeastern New Mexico: A Guide to Geology and Culture,

by William R. Muehlberger, Sally J. Muehlberger and L. Greer Price. New

Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, 2005. ISBN 1 8839 0520

6. Softcover, $14.95.

With more than 100 photos, maps and illustrations, High Plains is a virtual tour of northeastern New Mexico. This field guide, complete with field-trip stops, offers a view of the geologic landscape, such as Malpie Mountain volcano and the canyon of the dry Cimarron River, and gives the reader a sense of the cultural history of the region with a stop at the Folsom Man site and the Santa Fe Trail. Everyone can enjoy the grandeur and beauty of the sites described in this guidebook, but a caveat: The entirety of the book must be read to understand the authors’ references to particular named groups of outcrops.

Crater

Lake — Gem of the Cascades: The Geological Story of Crater Lake National

Park, Oregon, by K.R. Cranson. KRC Press, 2005. Softcover, $15.95.

Crater

Lake — Gem of the Cascades: The Geological Story of Crater Lake National

Park, Oregon, by K.R. Cranson. KRC Press, 2005. Softcover, $15.95.

Crater Lake’s majestic deep blue waters, which sit in a 10-kilometer-wide caldera enshrouded by tree-lined cliffs, have inspired native stories about the lake’s formation 7,000 years ago. In his third edition of Crater Lake, K.R. Cranson, a trained petroleum geologist who was an interpretive ranger at Crater Lake National Park for seven seasons, has set out to describe in more detail the geologic formation of the volcanic lake, which occurred after the collapse of Mount Mazama. The book, intended for park visitors, teachers and geologists, has some helpful features, such as a glossary, blank pages for notetaking and color plates of photos from the region.

Kids

Fun

With GPS, by Donald Cooke. ESRI Press, 2005. ISBN 1 5894 8087 2. Softcover,

$19.95.

Fun

With GPS, by Donald Cooke. ESRI Press, 2005. ISBN 1 5894 8087 2. Softcover,

$19.95.

What is Global Positioning System (GPS)? How does it work? How do you use it? These are some of the many questions that Cooke answers in this detailed and colorful book for kids. Starting with the basics of finding a location through latitude and longitude, Cooke explains with real-life examples and hundreds of pictures how GPS can be used for mapping, animal tracking, biking and skiing, and even land conservation. Filled with fun activities and experiments to try, and kid can find something interesting to do using GPS.

Adventure

on Dolphin Island, by Ellen Prager. iUniverse Inc., 2005. ISBN 0 5953

5791 1. Softcover, $14.95.

Adventure

on Dolphin Island, by Ellen Prager. iUniverse Inc., 2005. ISBN 0 5953

5791 1. Softcover, $14.95.

Ellen Prager, a marine geologist, has ventured into children’s fiction with Adventure on Dolphin Island. When heroine Kelly Wickmer is suddenly tossed from her parents’ rented sailboat, she finds herself floating helplessly in the ocean. Alone and scared, she is befriended by a dolphin who carries her to a fantastic, mysterious island. Folding science into this fictional adventure story, Prager introduces oceanography and marine biology to kids through Kelly’s story of being stuck on a tropical island and finally making the journey home.

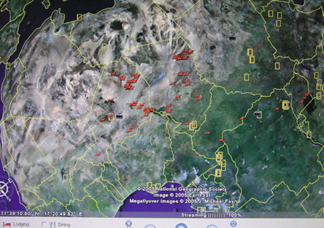

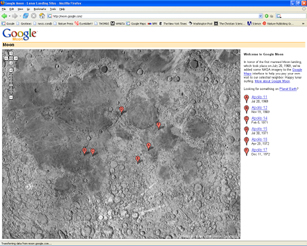

From

an astronaut’s point of view, Earth looks like a marble from space, but on

closer inspection, the seemingly empty planet becomes a well-populated and interconnected

globe. The same is true for Google Earth, the search engine company’s 3-D

representation of the planet that is dynamic, interactive and fully searchable.

From

an astronaut’s point of view, Earth looks like a marble from space, but on

closer inspection, the seemingly empty planet becomes a well-populated and interconnected

globe. The same is true for Google Earth, the search engine company’s 3-D

representation of the planet that is dynamic, interactive and fully searchable. One limitation

to using Google Earth may be bandwidth capacity, Nourbakhsh says. Although recent

developments allow real-time streaming of movies and other large data files, Google

Earth is starting to push up against bandwidth limits, particularly with very

high-resolution imagery now available (and higher resolutions will come in the

future). He says that addressing that problem could lead to advances in algorithms,

on the order of those that occurred two decades ago, when Internet bandwidth first

became a concern.

One limitation

to using Google Earth may be bandwidth capacity, Nourbakhsh says. Although recent

developments allow real-time streaming of movies and other large data files, Google

Earth is starting to push up against bandwidth limits, particularly with very

high-resolution imagery now available (and higher resolutions will come in the

future). He says that addressing that problem could lead to advances in algorithms,

on the order of those that occurred two decades ago, when Internet bandwidth first

became a concern.