While 2004 may

have been the year of debating the Cretaceous/Tertiary (K/T) extinction —

largely due to a new coring project off the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico —

2005 seems to have been all about the Permian/Triassic (P/T) extinction.

While 2004 may

have been the year of debating the Cretaceous/Tertiary (K/T) extinction —

largely due to a new coring project off the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico —

2005 seems to have been all about the Permian/Triassic (P/T) extinction.

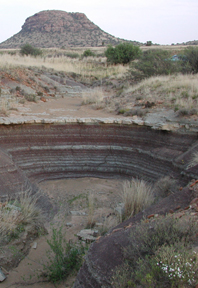

The Permian/Triassic boundary near the Caledon River in South Africa shows laminated

“event” beds from a mass extinction 251 million years ago. Research

from this locale, published this year, suggests a gradual extinction due to

increased temperatures and lowered oxygen levels. Courtesy of Peter Ward.

Often called the “Great Dying,” because up to 90 percent of marine

organisms and 70 percent of terrestrial organisms died off, the P/T extinction

remains quite a mystery, says Thomas Holtz, a paleontologist at the University

of Maryland in College Park. Scientists say that about 251 million years ago,

give or take a few hundred thousand years, the extinction occurred. The rest

is debatable, including causes of death, how long the extinction event lasted,

how quickly the creatures died and how the planet began its recovery.

At the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco last

December, heated debate continued over whether or not an impact could have caused

the extinction event, like the impact that happened at the K/T boundary and

killed the dinosaurs. Last year, Luanne Becker of the University of California

at Santa Barbara and colleagues reported finding evidence of an impact crater

off the coast of Australia that dated to the P/T boundary. Kenneth Farley of

Caltech in Pasadena reported at the meeting, however, an absence of extraterrestrial

elements or any impact evidence in P/T sediments from Canada, Antarctica or

Australia. Farley told Geotimes in April that while

his research does not “rule out” an impact, “there is a great

deal of doubt about an impact at that boundary.” The evidence just isn’t

there, he said.

Peter Ward of the University of Washington in Seattle further fueled the debate

when he and colleagues correlated P/T sediments from the Karoo Basin in South

Africa with equivalent-aged rocks from China. They found “a gradual extinction

leading to a sharp increase at the P/T boundary,” followed by a continued

extinction after the boundary, Ward told Geotimes in

April. This trend is consistent with long-term deterioration of the ecosystems

produced by increased temperatures and lower oxygen levels, Ward said.

At a Geological Society of America and Geological Association of Canada joint

meeting in August, Barry Lomax of the University of Sheffield in the United

Kingdom and colleagues presented findings supporting a large ozone hole and

rising levels of carbon dioxide — and thus an ensuing drop in oxygen levels

— at the end of the Permian, which could have led to some of the extinctions.

Lomax and colleagues suggested that the eruption of the Siberian Traps, a voluminous

flood basalt deposit that emitted carbon dioxide and other noxious gases, was

coincidental with the extinctions and thus could have been the cause of the

massive atmospheric changes (see Geotimes, October 2005).

Still other research, by Mark Maslin of University College London in the United

Kingdom and colleagues, suggested global warming at the end of the Permian caused

a destabilization of methane hydrates in the ocean, triggering a massive release

of methane into the atmosphere, as presented at the annual meeting of the Royal

Geographic Society in August. Because methane is 21 times more powerful as a

greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, the release would have led to incredible

global warming and atmospheric changes.

Whether it was a catastrophic event such as the K/T impact, the eruption of

the Siberian Traps or something else more gradual leading to the extinction

event, “it makes sense that there’s a lot of focus on the P/T,”

Holtz says, “as we know so little about it.” Learning more about the

speed of the extinction is certainly an area of important research, he says.

And in recent years, he says, it has been interesting to watch the interdisciplinary

nature of the research emerge as a new trend.

Megan Sever

Links:

"Ozone link to Permian extinction," Geotimes,

October 2005.

"Mass extinction, massive problem,"

Geotimes, April 2005.

Back to top

In April,

National Geographic Society and partners launched a new five-year study to genetically

track the human race’s ancient migration out of Africa (see Geotimes,

September 2005). The study is analyzing the DNA of indigenous people and

interested members of the public to determine when populations migrated and

what paths they took. It may also answer one of the most popular questions in

geoarchaeology — when and how people populated the Americas.

In April,

National Geographic Society and partners launched a new five-year study to genetically

track the human race’s ancient migration out of Africa (see Geotimes,

September 2005). The study is analyzing the DNA of indigenous people and

interested members of the public to determine when populations migrated and

what paths they took. It may also answer one of the most popular questions in

geoarchaeology — when and how people populated the Americas.

Rolfe Mandel of the University of Kansas cleans a mammoth bone at a site that

he and colleagues say may hold evidence of the oldest-known North American human

populations. Photo by Travis Heying, Wichita Eagle News; courtesy of Rolfe Mandel.

In the meantime, whether humans first entered the Americas around 11,500 years

ago (as dated through radiocarbon isotopes) via the Bering land bridge, or earlier

via some other means, remains a topic of hot debate. Last summer, at the Kanorado

site in Kansas, Rolfe Mandel of the University of Kansas in Lawrence and colleagues

found stratified artifacts and dated them to the two oldest known populations,

the Clovis and Folsom cultures. And “what’s even more intriguing,”

Mandel says, is that below these cultural deposits are 12,300-year-old mammoth

and camel bones with fracture patterns that may be products of human activity.

“This could be the earliest evidence yet of people on the Great Plains,”

he says.

And research elsewhere, such as the Big Eddy site in Missouri, the Topper site

in South Carolina and the Cactus Hill site in Virginia, also strongly suggests

that people were in the Americas before 11,500 years ago, Mandel says.

In more controversial work presented this fall, new dates from a site in Mexico

suggest that humans were in the Americas as long as 40,000 years ago. Researchers

found 269 individual footprints of anatomically modern humans and animals intermingled

in volcanic ash on the floor of an abandoned quarry. They recently dated the

volcanic ash and artifacts from the site to 40,000 years ago, Michael Bennett

of Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom told Geotimes

in September. Many researchers remain skeptical, however.

Over the coming year, Bennett and colleagues will be returning to the site for

more testing and excavation. And Mandel and others will continue their work

at Kanorado and other U.S. sites, all trying to figure out if the Clovis people

were the first Americans, or if there were others who came before.

Megan Sever

Links:

"Tracing

Human Migration," Geotimes, September 2005.

"Footprints push back American migration," Geotimes,

September 2005.

Back to top

More “hobbits”

in Indonesia

In October

2004, the world was shocked to learn that a new species of hominid had been

found on a remote Indonesian island. The hominid, nicknamed “hobbit”

for its diminutive size, lived until 18,000 years ago — well after the

last Neanderthals had died and anatomically modern humans had become dominant.

In 2005, controversy ensued over whether these bones represented a new species

called Homo floresiensis, after the island of Flores where the small

hominid was found, or an abnormal or pygmy Homo sapiens.

In October

2004, the world was shocked to learn that a new species of hominid had been

found on a remote Indonesian island. The hominid, nicknamed “hobbit”

for its diminutive size, lived until 18,000 years ago — well after the

last Neanderthals had died and anatomically modern humans had become dominant.

In 2005, controversy ensued over whether these bones represented a new species

called Homo floresiensis, after the island of Flores where the small

hominid was found, or an abnormal or pygmy Homo sapiens.

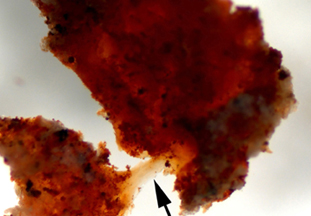

This year, scientists compared the braincase

from a new fossil find to modern humans, chimps and other hominids, to try to

determine if it belongs to a new species of diminutive hominid that lived until

18,000 years ago. Image courtesy of Peter Brown.

Paleoanthropologist Dean Falk of Florida State University joined the fray by

studying the braincase of H. floresiensis and determining that the hominid,

which was only about a meter tall and had the brain capacity comparable to that

of a chimpanzee, was indeed a new species. Falk compared the hobbit’s brain

to chimps, older hominids such as Homo erectus and Australopithecus

afarensis, modern humans, and modern humans with abnormalities. Quite simply,

she told Geotimes in May, “I’ve never

seen anything like this.” The researchers further postulated that the hobbit

might be a dwarfed descendent of H. erectus. Others remained unconvinced,

saying that the finding of one fossil specimen was not conclusive evidence that

H. floresiensis was indeed a new species of hominid.

Since the original skeleton was found, Peter Brown and Michael Morwood of the

University of New England in Australia (members of the original discovery team)

and colleagues have been back in the cave, looking for more specimens and evidence

of the hominid. On Oct. 13, they published findings in Nature indicating

the existence of nine more individuals. The finds, the authors wrote, “further

demonstrate that [H. floresiensis] is not just an aberrant or pathological

individual, but is representative of a long-term population” that lived

until at least 12,000 years ago, long after H. sapiens set foot in Australia

and Southeast Asia.

“It seems reasonable for Morwood and colleagues to stick to their original

hypothesis that H. floresiensis is a new species,” wrote Daniel

Lieberman in an accompanying commentary in Nature. But the researchers

themselves are now less convinced that the hobbit descended from H. erectus,

Lieberman pointed out, and the find “underscores just how little we know

about diversity within the human genus.” The discovery of more specimens

of H. floresiensis is “astonishing,” he wrote, but as always,

more and older fossils would help bolster the researchers’ arguments.

Megan Sever

Links:

"Inside the 'hobbit’s'

head," Geotimes, May 2005.

Back to top

One of the most

exciting studies in recent years is the discovery of soft tissue preservation

in a Tyrannosaurus rex fossil, says Kevin Padian, a paleontologist at the

University of California, Berkeley.

One of the most

exciting studies in recent years is the discovery of soft tissue preservation

in a Tyrannosaurus rex fossil, says Kevin Padian, a paleontologist at the

University of California, Berkeley.

Megan Sever

Links:

"Broken bones

yield T. rex tissue," Geotimes, May 2005.

Back to top

An evolving debate

At an Aug. 1, 2005, press conference, a reporter asked President Bush if he

thought that intelligent design (ID) — the belief that the complexity of

life is evidence that something intelligent must have designed it — should

be taught alongside the theory of evolution in public schools. His response

— that both should be taught — sparked nationwide attention.

But the debate over what to teach in public school science classes intensified

long before the August press conference. In January, ID proponents continued

with attempts from 2004 to change science curricula to either “teach all

sides” or reduce evolution to “only a theory.” Their efforts,

however, conflicted with the scientific method, as ID is not a testable scientific

alternative to evolution. As a result, the year 2005 was ripe with controversy

as the issue became a focus of the media, state legislation, kangaroo courts

and school science standards up for revision.

| Dover “is going

to be the case that apparently is going to test intelligent design.” Nick Matzke National Center for Science Education |

Events kicked off on Jan. 13 in Cobb County, Ga., when a judge ordered the

removal of disclaimers in science textbooks that warned “evolution is a

theory, not a fact,” under the ruling that they violated the First Amendment.

According to the National Center for Science Education (NCSE), the decision

set a “precedent for future cases dealing with antievolution policies in

public schools.” Appeals made by the school board were tentatively scheduled

to be heard by the United States Court of Appeals Eleventh Circuit on Dec. 12.

The state of Kansas has also received national attention this year for the continuing

controversy over the revision of the state’s public school science standards.

Hearings to discuss the opposing views were held in May, exposing the polarization

between ID supporters who testified and scientists who boycotted the event (see

Geotimes, October 2005).

The Kansas State Board of Education voted Nov. 9 in favor of changing the standards

to emphasize evolution as a theory and not fact, and literally changed the definition

of science to accommodate the possibility of an intelligent designer (see Geotimes

online, Web Extra, Nov. 9, 2005). In protest of the standards, the National

Academy of Sciences and the National Science Teachers Association withdrew copyright

permission for using their materials in the science standards.

And in Dover, Pa., a lawsuit filed in December 2004 challenged a previous decision

made by the local school board that called for biology teachers to revise their

curriculum and provide ID as an alternative to evolution — the first directed

teaching of ID in schools. The board had also required science teachers to read

a statement to biology classes that states that gaps exist in Darwin’s

theory of evolution and guides students to the book Of Pandas and People —

an ID book originally published in 1989 by the Foundation for Thought and Ethics.

In response to the lawsuit filed by students’ parents, much of the year

was spent gathering depositions, expert reports and expert witnesses on both

sides of the issue in preparation for the trial that began in September. An

early copy of Of Pandas and People was subpoenaed in a pretrial case this year,

which revealed that the modern version replaced the word “creation”

with “intelligent design.”

“That’s kind of a smoking gun,” says Nick Matzke of NCSE. Dover

“is going to be the case that apparently is going to test intelligent design.”

According to Eugenie Scott, director of NCSE, the trial, which concluded in

November (with no resolution as Geotimes went to press), was not likely

to rule in favor of ID.

In the meantime, Dover citizens voted out all eight school board members who

favored the inclusion of ID in the curriculum in the November elections, replacing

them with representatives who say ID does not belong in the science classroom.

Kathryn Hansen

Links:

"Evolution & Intelligent Design: Understanding Public Opinion," Geotimes, October 2005.

"Evolution battles

continue," Geotimes, Web Extra, Oct. 21, 2005

"Kansas vote challenges evolution," Geotimes

online, Web Extra, Nov. 9, 2005.

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |