Geotimes

Untitled Document

Travels in Geology

February 2006

Below Boston's hills

Selby Cull

"The

heart of the world beats under the three hills of Boston," wrote poet Oliver

Wendell Holmes around 1860. Above those hills is one of America's most revered

historical cities, and below them are rocks that span more than half a billion

years of Earth's history.

"The

heart of the world beats under the three hills of Boston," wrote poet Oliver

Wendell Holmes around 1860. Above those hills is one of America's most revered

historical cities, and below them are rocks that span more than half a billion

years of Earth's history.

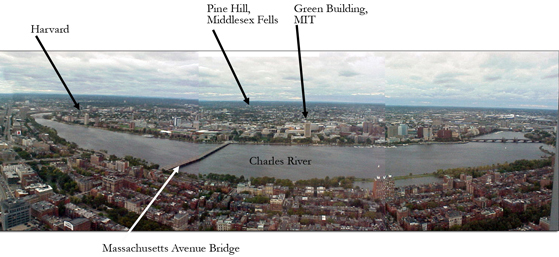

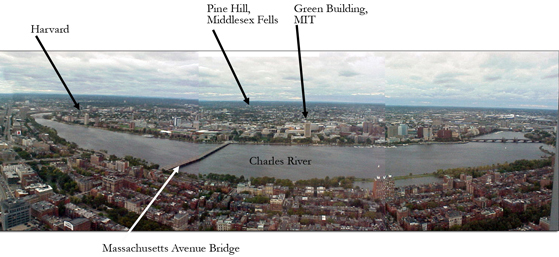

To experience Boston's geology, first get away from the rocks. Go to the middle

of the city, where every rock is paved over, and take the elevator to the 52nd

floor of the Prudential Building. There, four walls of

glass show you the entire Boston region.

The view from the top of Boston's Prudential

Building will give you more than just a cultural history of the city: You can

also see the geological remnants of glaciers, colliding continents and exploding

volcanoes. At the Middlesex Fells Reservation, for example,

visitors can hike or mountain bike among 630-million-year-old volcanic rocks.

All images by Selby Cull.

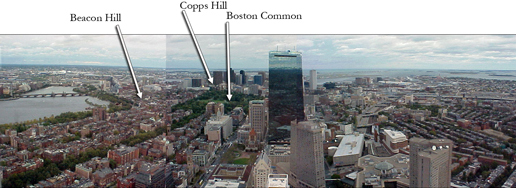

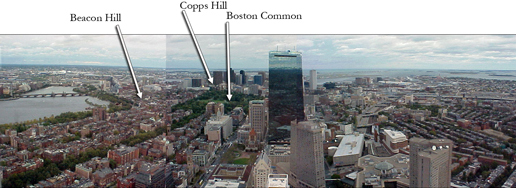

Podiums and exhibits in the viewing area highlight landmarks of the city's rich

history and culture: the gold-plated capitol dome atop Beacon Hill, where the

Puritan group led by John Winthrop settled in 1630; King's Chapel with the grave

of William Dawes, a patriot who rode with Paul Revere on his "midnight

ride"; and Bunker Hill, where a famed battle occurred between the colonists

and the British on June 17, 1775.

What the exhibits won't tell you is that the Puritans settled at the base of

Beacon Hill because it is made of stratified sand from a glacial outwash channel.

The layered deposits allow groundwater to flow and pool at the base, where the

settlers could collect it for drinking water. King's Chapel is built of 450-million-year-old

Quincy Granite, which formed when an island the size of Japan collided with

the island that carried Boston-to-be, long before it was part of North America.

Bunker Hill is a drumlin: a streamlined hill of compacted glacial debris, shaped

by a retreating glacier.

From

the Prudential Building, most of what you see below you is glacial debris. The

Wisconsin Ice Sheet, the last glacier to blanket New England, retreated about

16,000 years ago, leaving in its wake boulders and gravel it had carried down

from the North, and forming Cape Cod and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and

Nantucket. Around Boston, the glacier left dozens of drumlins and "kettles"

(bowl-shaped hollows created when glaciers melt), which form most of the ponds

of the city's "Emerald Necklace," one of the

oldest series of parks and parkways in the United States that are worth a visit

unto themselves.

From

the Prudential Building, most of what you see below you is glacial debris. The

Wisconsin Ice Sheet, the last glacier to blanket New England, retreated about

16,000 years ago, leaving in its wake boulders and gravel it had carried down

from the North, and forming Cape Cod and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and

Nantucket. Around Boston, the glacier left dozens of drumlins and "kettles"

(bowl-shaped hollows created when glaciers melt), which form most of the ponds

of the city's "Emerald Necklace," one of the

oldest series of parks and parkways in the United States that are worth a visit

unto themselves.

From the Prudential Building, you can

see Beacon Hill, where the Puritans settled in the 17th century. Beacon Hill

— the remains of a glacial outwash channel — provided a water source

for the early European settlers through its layered deposits.

But Boston's geology is much deeper and richer than the sculpted mounds of

glacial debris that dominate its topography. It is worth driving a bit to visit

some of the oldest rocks in the Boston area. First up would be the 630-million-year-old

Dedham Granodiorite at the Middlesex Fells Reservation.

You can take the subway or a bus, but it's far easier to grab your car and

head north on Interstate 93, about 10 kilometers (6 miles) to the Middlesex

Fells Reservation — to hills that are anything but glacial. The reservation,

comprising 2,060 acres of wetlands and oak forests, sits on 630-million-year-old

granodiorite (volcanic rock) with a large 200-million-year-old basaltic dike.

At the reservation, visitors can hike several trails, mountain bike down the

steep granite hills or take a boat out on Spot Pond, another kettle hole left

by the retreating ice sheet. The Pine Hill trail is an easy starter trail, with

views of the ancient rocks, as well as a breathtaking view of Boston.

Other

local parks offer further glimpses into the deep past, if you have the time

and inclination. Sixteen kilometers up the coast from the Fells is Castle Rock

in Marblehead Neck, a favorite field trip of geology classes and rock climbers

because of its interesting "swirled" texture. This 600-million-year-old

volcanic rock is all that's left of the explosive volcanoes that once dominated

the Boston area, before they eroded away to nothing.

Other

local parks offer further glimpses into the deep past, if you have the time

and inclination. Sixteen kilometers up the coast from the Fells is Castle Rock

in Marblehead Neck, a favorite field trip of geology classes and rock climbers

because of its interesting "swirled" texture. This 600-million-year-old

volcanic rock is all that's left of the explosive volcanoes that once dominated

the Boston area, before they eroded away to nothing.

A short jaunt up the coast from Boston

is Castle Rock in Marblehead Neck, where the "swirling" rocks provide

a history lesson on 600-million-year-old volcanoes to rock climbers and geology

students alike.

Just south of downtown Boston, near the town of Quincy, Squaw Rock Park offers

a look at some 570-million-year-old rocks, which some researchers think were

deposited during the "snowball Earth" ice age at the end of the Proterozoic.

These ancient sedimentary rocks can be found along the park's small northern

beach, which also offers a beautiful view of Boston Harbor and the Boston skyline.

Quincy

itself has a fascinating geologic history, as a town made famous by its quarrying

industry. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the 450-million-year-old

Quincy Granite was such a popular building material that the quarry owners built

America's first railroad to transport the granite to New England cities. The

railroad is no longer in use, but you can find the old start of the tracks at

the end of Mullin Avenue. And although the quarries are now all closed, you

can still find excellent outcrops of the granite along Route 53 and Route 3A.

Quincy

itself has a fascinating geologic history, as a town made famous by its quarrying

industry. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the 450-million-year-old

Quincy Granite was such a popular building material that the quarry owners built

America's first railroad to transport the granite to New England cities. The

railroad is no longer in use, but you can find the old start of the tracks at

the end of Mullin Avenue. And although the quarries are now all closed, you

can still find excellent outcrops of the granite along Route 53 and Route 3A.

Just south of Boston is Squaw Rock Park,

where visitors can see 570-million-year-old rocks that some researchers think

were deposited during the "snowball Earth" ice age.

Slightly younger but equally interesting rocks can be found at another historic

site, just west of Boston, at Minute Man National Historic

Park, where the famous "shot heard round the world" started the

American Revolution in 1775. There, British soldiers used the 425-million-year-old

Bloody Bluff Fault as a rallying point before beginning their retreat. The fault

is visible on a spectacular outcrop in the park, which is about half an hour

northwest of downtown Boston. While you're there, stop by the visitor's center

to reacquaint yourself with the human history. And if you have the time, walk

or bike the easy 8-kilometer Battle Road Trail through the park.

After your trek through the Boston area's long and varied geologic history,

stop in at a pub for a pint and a bowl of clam chowder in the venerable Boston

tradition. If the clams ("quahogs" in Boston parlance) are from the

harbor, they grew on top of a continental shelf made of 550-million-year-old

slate — who can resist? And while you're there, be sure to also try the

city's famous baked beans and Boston cream pie.

Getting to Boston is pretty easy, no matter what time of year you visit. Most

flights go through Logan Airport, but flying through Providence, R.I., is also

an option, as the airport is less than an hour away. Boston is also an easy

drive or train ride up the Interstate-95 corridor that runs along the entire

East Coast. Most visitors stay in Boston's Back Bay district or Cambridge, across

the river, where lodging abounds. Hotel rooms tend to fill up quickly in mid-April

for the Boston Marathon, at the end of May for college graduations and near

the July 4 holiday, so if you're heading to Boston during those times, book

early.

Cull studied geology

at Hampshire College and is now a Boston-based rockhound, doing graduate work

at MIT.

Links:

Prudential

Center Skywalk

Middlesex

Fells Reservation

Minute

Man National Historic Park

City

of Boston parks

Boston

Visitor's Bureau

Travels in Geology

Back to top

Untitled Document

"The

heart of the world beats under the three hills of Boston," wrote poet Oliver

Wendell Holmes around 1860. Above those hills is one of America's most revered

historical cities, and below them are rocks that span more than half a billion

years of Earth's history.

"The

heart of the world beats under the three hills of Boston," wrote poet Oliver

Wendell Holmes around 1860. Above those hills is one of America's most revered

historical cities, and below them are rocks that span more than half a billion

years of Earth's history.

From

the Prudential Building, most of what you see below you is glacial debris. The

Wisconsin Ice Sheet, the last glacier to blanket New England, retreated about

16,000 years ago, leaving in its wake boulders and gravel it had carried down

from the North, and forming Cape Cod and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and

Nantucket. Around Boston, the glacier left dozens of drumlins and "kettles"

(bowl-shaped hollows created when glaciers melt), which form most of the ponds

of the city's "

From

the Prudential Building, most of what you see below you is glacial debris. The

Wisconsin Ice Sheet, the last glacier to blanket New England, retreated about

16,000 years ago, leaving in its wake boulders and gravel it had carried down

from the North, and forming Cape Cod and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and

Nantucket. Around Boston, the glacier left dozens of drumlins and "kettles"

(bowl-shaped hollows created when glaciers melt), which form most of the ponds

of the city's " Other

local parks offer further glimpses into the deep past, if you have the time

and inclination. Sixteen kilometers up the coast from the Fells is Castle Rock

in Marblehead Neck, a favorite field trip of geology classes and rock climbers

because of its interesting "swirled" texture. This 600-million-year-old

volcanic rock is all that's left of the explosive volcanoes that once dominated

the Boston area, before they eroded away to nothing.

Other

local parks offer further glimpses into the deep past, if you have the time

and inclination. Sixteen kilometers up the coast from the Fells is Castle Rock

in Marblehead Neck, a favorite field trip of geology classes and rock climbers

because of its interesting "swirled" texture. This 600-million-year-old

volcanic rock is all that's left of the explosive volcanoes that once dominated

the Boston area, before they eroded away to nothing. Quincy

itself has a fascinating geologic history, as a town made famous by its quarrying

industry. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the 450-million-year-old

Quincy Granite was such a popular building material that the quarry owners built

America's first railroad to transport the granite to New England cities. The

railroad is no longer in use, but you can find the old start of the tracks at

the end of Mullin Avenue. And although the quarries are now all closed, you

can still find excellent outcrops of the granite along Route 53 and Route 3A.

Quincy

itself has a fascinating geologic history, as a town made famous by its quarrying

industry. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the 450-million-year-old

Quincy Granite was such a popular building material that the quarry owners built

America's first railroad to transport the granite to New England cities. The

railroad is no longer in use, but you can find the old start of the tracks at

the end of Mullin Avenue. And although the quarries are now all closed, you

can still find excellent outcrops of the granite along Route 53 and Route 3A.