|

Education & Outreach

Teachers Face Desert Heat of Spaceward Bound

When Geoff Hammond is not teaching his fifth-grade class in Huntington Beach, Calif., he can likely be found outdoors, training for an Ironman triathlon or leading a rock climbing trip. Such experience in the outdoors might be one reason that NASA chose Hammond for the 2006 Spaceward Bound program, Hammond says.

When Geoff Hammond is not teaching his fifth-grade class in Huntington Beach, Calif., he can likely be found outdoors, training for an Ironman triathlon or leading a rock climbing trip. Such experience in the outdoors might be one reason that NASA chose Hammond for the 2006 Spaceward Bound program, Hammond says.

The ultimate goal of Spaceward Bound is to “train the next generation of space explorers,” according to NASA, which, along with the Mars Society, organizes the program. Toward that goal, teachers of upper-elementary and middle school students are selected once a year to head out to an extreme environment on Earth that resembles conditions on the moon or Mars, to work alongside scientists and then bring that experience back to the classroom.

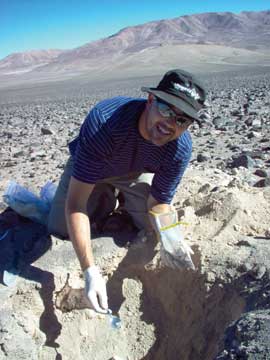

Fifth-grade teacher Geoff Hammond helps test for organic matter in the soil in Chile’s Atacama Desert, which resembles the extreme environment of Mars. Such Earth-based research might help researchers know where and how to look for life on Mars. Photograph is courtesy of Geoff Hammond.

As a fifth-grade teacher, Hammond teaches all subjects. “I’m not specifically a science teacher,” he says, noting that prior to the trip his background in science was “a bit lacking.” That would soon change, however, when the program’s inaugural group of seven teachers, including Hammond, was selected to travel to Chile’s Atacama Desert. The martian-like “laboratory” offered scientists a chance to test out ideas that might aid in the search for life on Mars, and also provided information that might help future human travel to and survival on the planet.

To prepare for the trip to the Atacama, Hammond met with NASA scientists Chris McKay and Liza Coe. Hammond researched the Atacama Desert and other Mars analogue sites to learn about each site and the research that the scientists are conducting there.

When Hammond finally made his foray into the desert he found that indeed, outdoor adventures have connections with science. Hammond took time after his expedition to chat with Geotimes reporter Kathryn Hansen about climbing volcanoes in the desert and working alongside NASA scientists as they studied life in a desolate region on Earth that resembles Mars, and how the excitement of the experience will translate to his students during the 2006-2007 school year. “All of these experiences have been really eye-opening,” he says.

KH: Tell me about the expedition and its unusual location.

GH: It was basically an expedition to the Yungay, a region of the Atacama Desert, which is supposed to be one of the driest places in the world. NASA has a Mars analogue research facility there, where they do experiments and testing. It’s a Mars analogue site because of the landscape and how dead and lifeless it is: It’s about as close as they could get to something similar to Mars without actually having to go there. They use it to test things and to experiment, to test equipment and procedures that they would use somewhere else.

KH: What was it about the program that appealed to you?

GH: It sounded like a really fun adventure first of all, and something that was right up my alley. It was definitely off the beaten path. There would be some travel and camping and more roughing-it-style activities, which I like.

KH: Once you headed out, whom did you work with?

GH: There were probably 10 to 12 scientists with us in the group, and each one is really specialized in their specific field. During our two-day drive to the station after we landed in Santiago, the teachers paired up with different scientists. I ended up working most closely with molecular scientist Linda Powers, from Utah State, who was there with her assistant.

KH: What type of research did you do?

GH: They had a special sensing machine that they brought with them. We hooked it up to a laptop and were able to get instantaneous results from analyzing soil. We would put a little bit of soil on a plate that was inserted into the machine, and then we could see in the soil how much organic matter was present — everything from bacteria, spores and cells, to plant or animal matter.

KH: Did you shadow Linda for the duration of the expedition?

GH: Yes, we were together with the main group for the first four days. But Linda had planned to go get some dirt samples from higher elevation, so Linda, her assistant, I and one other teacher broke off from the main group to go and climb a couple volcanoes. We were gone for the rest of the trip and didn’t meet up with the rest of the group again until back at the airport in Santiago.

KH: Tell me more about climbing the volcanoes.

GH: We climbed all the way to the top of a volcano named Lascar, which was 18,025 feet [5,494 meters] tall. That was very challenging. We started out driving from San Pedro, which is at about 3,000 feet [914 meters] in elevation. In fact we drove up to almost 15,000 feet [4,572 meters]. Then we had to get guides to have a professional take us up to the rim. Lascar is a recently active volcano so when we got to the rim there were still fumes coming out and it’s really sulfuric and bad-smelling. You look at the crater at the top and it’s huge, you could look over the rim and it just drops away into nothing. You can’t see the bottom. We got samples right from the rim, and then about 10 meters back from the rim and then 100 meters down, and then another one about halfway down.

KH: How has your understanding of NASA’s research changed?

GH: I found it fascinating working with the scientists in their fields and seeing how excited they were about things you and I would never look at twice — different things in the soil and different colors in the soil.

KH: How do you plan to incorporate what you learned into the classroom?

GH: My plan is to put together a PowerPoint presentation of the whole trip. I plan to use it in conjunction with social studies, which in 5th grade focuses on U.S. history. We do a big unit on Lewis and Clark, and I want to use this Spaceward Bound expedition to compare and contrast.

KH: What do you hope your students will take away from this?

GH: I hope that it opens their eyes and gives them a more real-world experience of science and maybe sparks an interest in some of them, by showing them real science at work, the kinds of things you can do as a scientist; that it’s not just boring locked-in-a-lab-all-day work.

KH: Is there anything else you would like to say about this program?

GH: I think overall, the Spaceward Bound program for me has brought a whole new aspect, a whole new level to my teaching as a whole, and has gotten me more excited and energized all over again. I think that’s one of the main reasons for doing this kind of thing — to get the teachers excited — and that transfers right over to the students, and it helps get them excited.

Subscribe

Subscribe