In 1999, the International Association of Sedimentologists published two important Special Publications, v. 27 (Fluvial Sedimentology VI) and v. 28 (on paleoweathering). Both offer much to think about, such as Russell's description of the 1996 jokulhlaup in Iceland, Thiry's silcretes and Schwarz's polyphase saprolites. Tropical soil sedimentology, moribund too long, should be contributing to exciting recent upheavals in tropical terrestrial biosciences (e.g., Missouri Botanical Garden Annals, v. 86, p. 546, 1999).

Blair's studies of adjacent but very different alluvial fans in Death Valley (Sedimentology, v. 46, p. 913, p. 941, and p. 1015) showed that one was almost entirely mudflows and the other was almost all sheetfloods, because of bedrock differences. Surprisingly, both lacked expected proximal-distal facies trends.

Seas and lakes

Coastal studies benefited from a special issue (Geologie en Mijnbouw, v. 77, issue 3/4) on climate-related changes in European coasts, including a neat synthesis of eolian facies in Spain. The detail possible in interpretation is increasingly impressive. Pleistocene shoreline specialists are now carefully contrasting interglacials (lengthy interglacial stage 11 seems comparable to today and sea levels may have been about 13 meters higher (Science News, v. 157, p. 138, 2000). See also documentation of massive sedimentation on floodplains, shelves, and fans during highstands (Goodbred and Kuehl, Geology, v. 26, p. 559, 1999), and eustatically forced changes in coastal-plain interfleuve soils (McCarthy and others, Sedimentology, v. 46, p. 861, 1999).

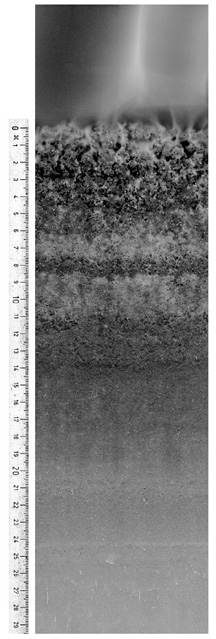

Sulfur print showing the different layers in the

sediment of lake Cadagno in southern Switzerland.

Christine Lehman.