geotimesheader

News

Notes

Planetary

Geology

Spouting

off about Io

| More than 100 volcanoes vent sulfurous material

onto the surface of Jupiter’s moon Io. Recent observations have shed light

on several of the volcanic phenomena, some of which have remained enigmatic

since Voyager first visited the jovian system more than 20 years

ago.

The largest volcanic plume observed by Voyager

rose 300 kilometers above the volcano Pele. Following observations made

by the Galileo spacecraft and the Hubble Space Telescope in the mid- to

late-1990s, scientists believed the plume contained sulfur dioxide gas.

In the May 19 issue of Science, a team of researchers led by John

R. Spencer of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., reported that

they also observed gas containing a rare compound of sulfur (S2)

emanating from Pele.

Using images from Hubble, they isolated the spectral

absorption of the sulfur gas against the background of Jupiter’s spectra.

The Hubble discovery is only the third astronomical observation of the

UV-radiation-sensitive S2, the others being from comets and

the impact sites of Shoemaker-Levy 9 on Jupiter.

|

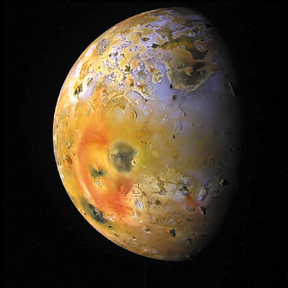

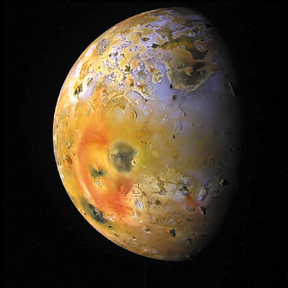

In this enhanced color composite of Io, deposits of sulfur dioxide

frost appear as white and gray hues. Other sulfurous materials

appear as yellow and brownish hues. Bright red materials, such as

the prominent ring surrounding Pele, and "black" spots with low

brightness mark areas of volcanic activity. NASA/JPL. |

The researchers also suggested that the sulfur

may polymerize into reddish compounds that could give Io its distinctive

coloration. Modeling currently underway by Julie Moses of the Lunar and

Planetary Science Institute in Houston may help determine whether condensing

S2 gas is the culprit behind the colored surface.

In the same issue of Science, a team of

researchers led by Susan W. Kieffer of S.W. Kieffer Science Consulting

Inc. in Ontario, Canada, presented a model to explain the wandering of

the gaseous plume emanating from Io’s volcano Prometheus. The plume has

wandered 85–95 kilometers from the point of its discovery by Voyager

in 1979, to the location recently observed by the Galileo probe. “The observation

team and I realized that we had a major challenge in explaining this wandering,”

Kieffer says, “because we have never seen it on Earth.” According

to Kieffer, the goal was to devise a testable hypothesis for how the plume

could remain active for 20 years and still maintain its constant shape

and optical properties. The researchers show that the critical property

is the plume’s mass flux, which must remain unchanged for the 20-year period.

The researchers propose that the wandering can

be explained by the vaporization of a “snowfield” of sulfur compounds over

which a lava flow is moving. The melted, sulfurous fluid at the base of

the lava erupts to the surface much like a rootless conduit on Earth (an

eruption conduit that is not attached to a magma chamber).

In the May 4 issue of Nature, Amara L.

Graps and a team of researchers led by Eberhard Gruen of the Max-Planck-Institut

für Kernphysik in Germany pinpointed Io’s volcanoes as the source

for a far-reaching dust stream that emanates from the jovian system. Using

data from Galileo’s Dust Detector System, the researchers were able to

observe both the frequency of dust emission and the general sizes of the

particles.

The team determined the strong likelihood of an

Io volcanism source and eliminated other potential sources, such as Jupiter’s

gossamer ring and Io’s impact ejecta. While the dust composition is most

likely sulfurous, “it’s a difficult measurement,” Graps says. “People doing

chemical analysis and interpretation of dust particles . . . are sometimes

surprised with what their spectra look like. This is a new field.”

The analyses of the Io dust stream will hopefully

come in December. That is when the Cassini space probe will join

Galileo to observe Io, and the combination of its onboard Cosmic Dust Analyzer

and Galileo’s Dust Detector System may allow researchers to determine an

accurate composition.

Josh Chamot

Geotimes contributing

writer