|

NEWS NOTES

Methane on the rise

NOAA |

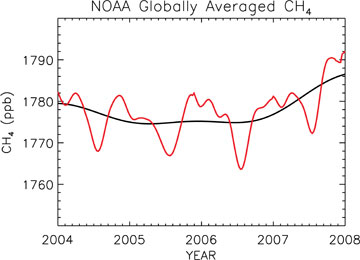

| Global methane (CH4) concentrations rose in 2007. The red line shows the trend together with seasonal variations. The black line indicates the trend that emerges when the seasonal cycle has been removed. |

After a nearly decade of stability, global atmospheric concentrations of methane grew by 21 million tons last year — about 0.5 percent. Humans release methane into the atmosphere by raising livestock, growing rice, burying garbage and extracting fossil fuels. But scientists at NOAA, who rely on 60 monitoring stations scattered around the globe to track greenhouse gas concentrations, don’t think the most recent jump is directly related to any of these activities.

“We think it’s the wetlands,” says Lori Bruhwiler, a physical scientist at NOAA Earth Systems Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colo. Microbes that feast on dead plants in low-oxygen environments — like bogs, swamps and fens — pump out methane. The warmer the weather, the more methane they produce. It was extremely warm in the Arctic last summer, Bruhwiler says, especially in wetland areas such as western Siberia.

Earth’s atmosphere now contains more methane than at any other time during the past 400,000 years. Between the mid-1700s and the late 1990s, global average atmospheric concentrations of methane more than doubled. But then, in 1998, methane plateaued at about 1,775 parts per billion. Elaine Matthews, a methane expert at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, N.Y., attributes the stabilization to the collapse of the Soviet Union. When that happened, she says, animal populations and coal production declined significantly. Other scientists, however, attribute the stabilization to widespread drought or fewer leaks from oil and gas pipelines and storage facilities.

One group suggested that wetlands may have been at least partially responsible for the stabilization. In 2006, Philippe Bousquet of the Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement in Gif-sur-Yvette, France, Ed Dlugokencky, who works with Bruhwiler at NOAA, and colleagues reported in Nature that declining methane emissions from wetlands had actually been masking rising inputs from China’s booming economy during the past decade.

Whatever the cause, the decade-long hiatus appears to be over. Bruhwiler and her colleagues can’t say yet whether the 2007 increase is an anomaly or the beginning of a long-term trend. That will depend, at least in part, on future climate change. “If it’s both warmer and wetter where the wetlands are, then methane emissions will go up. If it’s cooler and drier, then methane levels should fall,” Matthews says. “If it’s a combination, then you really don’t know what they’ll do.”

Climate models predict that a warming planet will lead to more methane production from existing wetlands as well as the formation of new methane-producing wetlands, especially in the Arctic. Methane is more than 20 times better at trapping heat than carbon dioxide is, which means it could trigger even more warming, thawing and methane production. That may happen, Matthews says, or it may not. In some cases, a solid layer of permafrost may be what’s holding water at the surface, she says. If that permafrost thaws, standing water might be able to drain. The surface would then be drier, and methane would stay locked in soils.

Dlugokencky says it is impossible to distinguish between methane from existing wetlands and methane from new wetlands being formed by permafrost thaw. So there’s no telling whether 2007 marks the beginning of a shift in Arctic methane releases. What he and Bruhwiler can say is that the jump in methane is not related to biomass burning, the other factor that tends to cause large, rather sudden increases in atmospheric methane. If the extra methane had come from fires, he and Bruhwiler would have also seen an increase in carbon monoxide.

Although the 2007 increase appears to be non-anthropogenic, human contributions are on the rise as well. Not only are animal populations in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe recovering, Matthews says, but coal production in Asia has skyrocketed.

Methane can vary significantly from one year to the next, but the long-term forecast doesn’t look good: “I think methane will increase again,” Bruhwiler says. “It’s not a bad idea to worry.”

Subscribe

Subscribe