geotimesheader

News

Notes

Atmospheric

Sciences

Hailstones

fall from clear Spanish skies

On Jan. 8, news spread through the media in Spain that a chunk of ice

fell from clear skies and hit a car in Tocina, a village close to Seville.

The piece broke into two pieces, one weighing 1.2 kilograms and the other

1.7. Between Jan. 8 and Jan. 31, at least 50 such falls were reported.

| Documented references of blocks of ice falling from clear skies go

back to the first half of the 19th century (e.g. 1829 in Córdoba,

Spain: 2 kg; 1851 in New Hampshire: 1 kg). Recent cases include a 9-kilogra,

fall in Batley, West Yorkshire in 1991. Probably the best-documented fall

of an ice chunk was April 2, 1973, in Manchester, England. The block weighed

2 kilograms and consisted of 51 layers of ice. Its origin was not determined.

Though some of the recent falls in Spain have been confirmed as practical

jokes perpetrated after initial reports of the phenomenon — people froze

large quantities of tap water and left the blocks of ice close to a public

area or road — we have verified the authenticity of nine falls (more than

10 kilograms of ice) that occurred from Jan. 8 to Jan. 17.

Chemical and isotopic analyses were performed in five of the specimens.

Our results offer evidence of chemical and isotopic heterogeneity (even

within each block), with large densities of ions — up to five times larger

than normal meteoric waters — and corresponding to solutions of halite,

calcite, anhydrite and quartz or feldspar aerosols. |

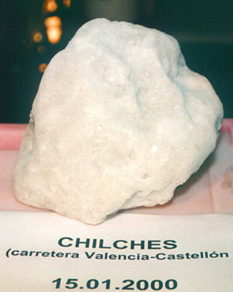

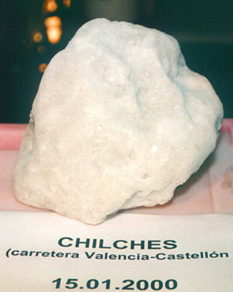

This

chunk of ice from Chilches (in

eastern

Spain) weighed four kilograms

and measured

20 by 26 centimeters.

Martinez-Frias

et al. |

The distribution of the samples on Craig’s meteoric water line suggests

either a variation in condensation temperature or isotopic exchanges during

the formation of each ice chunk. These data, together with the high frequency

of the events, indicate that the chunks aren’t minicomets and didn’t come

from aircraft. They may result from an atmospheric phenomenon.

A hailstone is a product of the updrafts and downdrafts that develop

inside the cumulonimbus clouds of a thunderstorm, where supercooled water

droplets exist. The change of droplets to ice necessitates not only a temperature

below 0 degrees Celsius, but also a catalyst in the form of tiny particles

of solid matter that become freezing nuclei. Continued deposits of super-cooled

water cause the ice crystals to grow into hailstones. Hailstones have been

found as large as grapefruits and weighing up to 7.5 pounds.

The possible explanation for how the recent ice chunks form may hinge

on the classical nucleation and growth processes. We assume that at the

high region of the atmosphere (i.e., 6 kilometers) the vapor water saturation

may be near equilibrium. It is well known that both the energy of nucleation

and the critical nuclei that can eventually grow tend to infinity if saturation

is close to one. Therefore the ice could not be formed under these conditions.

However, if conditions for extra cooling exist — large concentrations of

ions, aerosols, etc — then the nucleation energy reduces (heterogeneous

nucleation) and the nuclei that can grow are formed. Another possibility

could be that a crystallite from the lowermost stratosphere enters a region

of humidity, where it begins growing.

Ozone distribution maps from NASA show that, on Jan. 5, a thin jet of

ozone depression passed through all the areas in Spain where the ice falls

took place. It is commonly posited that global warming and ozone depression

are linked. Despite the fact that the greenhouse effect leads to an increase

in the global mean surface temperature, it leads to cooling in the stratosphere.

Perhaps the aforementioned nucleating crystallites enter the upper troposphere.

There, where humidity is more abundant, they start growing, evidencing

that the greenhouse effect is beginning to show. We suggest paying more

attention to the fall of these unusual chunks of ice, which could be indicating

that changes are taking place in the atmosphere.

Submitted by:

Jesús Martínez-Frías, Departamento

de Geología, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid, Spain;

Fernando López-Vera, Departamento de Geología, Geoquímica

y Química Agrícola, Madrid, Spain; Nicolás García,

Laboratorio de Fisica de Sistemas Pequeños, Madrid, Spain; Antonio

Delgado, Departamento de C.C. de la Tierra y Química Ambiental,

Granada, Spain; Roberto García, Laboratorio de XRD y Electroforesis,

MNCN, Madrid, Spain; Pilar Montero, Instituto del Frío, Madrid,

Spain