Geotimes

Technology

The Infrasound Renaissance

Megan Sever

On April 23, 2001, scientists manning a network designed to detect covert nuclear

tests noticed something unusual — a very “loud” sound coming

from above the Pacific Ocean. This global network, consisting of sensitive sound-recording

instruments, had picked up on a large meteor slamming into the atmosphere several

hundred miles west of Baja California, and exploding with a force comparable

to that of the nuclear bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

On Feb. 1, 2003, these same instruments heard something else — the Space

Shuttle Columbia reentering Earth’s atmosphere on its tragic final mission.

NASA subsequently used those recordings to rule out potential causes of the

mission’s demise, including a bolide or missile impact.

The sensitive instruments that recorded the meteor’s entrance and the end

of the Columbia record a range of low-frequency sound that is inaudible to the

human ear called infrasound. “It’s sort of like infrared light, which

is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that we can’t see, in that

it’s the part of the sound spectrum that we can’t hear,” says

Michael Hedlin, a geophysicist and infrasound specialist at the University of

California, San Diego, and Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The instruments detect atmospheric noise, such as storms, winds, volcanic eruptions,

ocean waves and airplane traffic, and they help scientists understand “just

what’s going on out there,” Hedlin says. “Right now, we’re

just listening to the world,” he says, but soon, the researchers will begin

to more fully comprehend the interactions between solid earth, the oceans and

the atmosphere.

An explosive history

When the Krakatoa volcano erupted in Indonesia in 1883, the eruption was so

explosive that it sent low-frequency sound waves around the world several times.

Scientists noticed the sound waves through air pressure changes measured by

barometers. That was the first recorded instance of infrasound.

Around the turn of the 20th century, scientists recorded a giant meteor exploding

above Russia. During World War II, the instruments recorded aircraft movement

and munitions explosions. During the Cold War, scientists and the U.S. Department

of Defense used the instruments to monitor nuclear bomb tests in the atmosphere.

Then in the late 1960s, the application of infrasound for monitoring nuclear

tests around the world became limited by the development of reliable satellite

technology, which could see atmospheric nuclear explosions and the subsequent

onset of underground testing, which was monitored by seismic data. “So

the field sort of went away for 30 years,” says Milton Garces, a volcanologist,

oceanographer and infrasound specialist at the University of Hawaii. “But

luckily, there were a few individuals who kept the knowledge alive,” he

says. And then, in 1996, the world adopted the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty,

which brought about “a renaissance for infrasound,” Garces says.

To enforce compliance with the treaty, the United Nations created the International

Monitoring System (IMS), a network of geophysical sensor stations located around

the world that monitor seismic signals, atmospheric radioactive material releases,

hydroacoustic signals and infrasound, Hedlin says (Geotimes, October

2002). Luckily, he says, so far they haven’t heard any nuclear tests —

only a plethora of atmospheric sounds.

At work

The IMS

infrasound network will eventually contain about 60 stations somewhat evenly

distributed around the world, but it is only about one-third complete right

now, Garces says. “We hope it’ll be all up and running in the next

couple of years,” he says, “but that might be a little optimistic.”

Nevertheless, the scientists are already recording more information than they

can comprehend, he says.

The IMS

infrasound network will eventually contain about 60 stations somewhat evenly

distributed around the world, but it is only about one-third complete right

now, Garces says. “We hope it’ll be all up and running in the next

couple of years,” he says, “but that might be a little optimistic.”

Nevertheless, the scientists are already recording more information than they

can comprehend, he says.

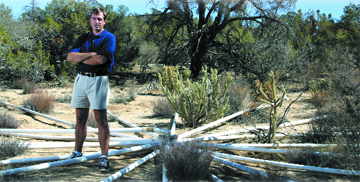

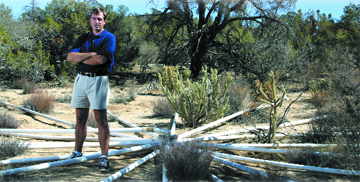

Geophysicist Michael Hedlin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography monitors

an international network of infrasound stations, like this one south of Palm

Springs, Calif. The sensitive instruments that measure low-frequency sound waves

resemble thermoses surrounded by wagon-wheel spokes of PVC piping. Photo by

Fred Greaves, Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The infrasound instruments (microbarometers) work similarly to basic barometers

that meteorologists use to detect weather patterns through atmospheric pressures.

Resembling large thermos bottles, the microbarometers contain sensitive electronic

instruments that convert atmospheric pressure to an electric signal. The sensors

are connected to white wagon-wheel spokes of PVC piping that filter “unimportant

sounds from important sounds,” Garces says, and keep animals and debris

away.

The instruments constantly measure ambient atmospheric sound waves and transmit

them to the International Data Center in Vienna, Austria, which keeps all data

related to the test ban treaty. The data then go to a data center in McLean,

Va., and also back to the lab that operates the station, where the scientists

do their own analysis in-house, Garces says.

“Truthfully, most of the time we don’t know what we’re listening

to,” says Henry Bass, a physicist and infrasound specialist at the University

of Mississippi. “We receive hundreds of thousands of signals each year

and we can only tell what a small fraction of them are,” he says. But the

more the scientists listen, the better they get at differentiating one sound

from another and picking out the important information from the clutter.

“Each station is kind of like your neighborhood,” Garces says. “You

live there for a year and slowly begin to understand what’s going on, all

of the idiosyncracies of your neighbors. You have that chatty neighbor —

you train yourself to cut out all the chatter and learn to recognize what is

important. That’s what we do with each station.”

After three years of continuous observation, the scientists are now beginning

to see patterns and differentiate the sounds emanating from storm fronts, explosions,

ocean waves, volcanoes and jet airplanes. For example, Garces says, “the

ocean is always singing in this deep bass voice. Now we know what its tune is,

so we can pick up on swells and storms.”

The researchers have also noticed strong seasonal patterns, Hedlin says, which

has been “really exciting.” From the station nearest San Diego, for

example, the researchers hear a lot more signals from the west in the winter

and from the east in the summer, which is related to seasonal wind patterns.

In general, stations will pick up atmospheric sounds from hundreds to thousands

of miles away, Hedlin says, but those data are not well understood yet. The

scientists monitoring the transmissions can always tell the direction of the

recording, but the distance is harder to discern. Furthermore, depending on

winds and the strength of a signal, the stations can register waves from around

the world.

Ash warnings

Hedlin, Garces

and Bass work on a number of applications in concert, although each has their

own pet project. Hedlin pays close attention to storms in the Pacific. Garces

concentrates on infrasound emitted from the constantly erupting Hawaiian volcanoes

as well as sounds of the ocean. Bass focuses on using infrasound to create a

3-D image of the internal structures of the atmosphere (tomography). Together,

all three scientists are developing a project that uses infrasound to create

a volcanic ash warning system for airplanes.

Hedlin, Garces

and Bass work on a number of applications in concert, although each has their

own pet project. Hedlin pays close attention to storms in the Pacific. Garces

concentrates on infrasound emitted from the constantly erupting Hawaiian volcanoes

as well as sounds of the ocean. Bass focuses on using infrasound to create a

3-D image of the internal structures of the atmosphere (tomography). Together,

all three scientists are developing a project that uses infrasound to create

a volcanic ash warning system for airplanes.

To airplane pilots, ash escaping from erupting volcanoes, such as Mount St.

Helens (pictured here), can resemble normal clouds. Scientists can use infrasound

to divert planes around erupting volcanoes. Courtesy of USGS, Cascades Volcano

Observatory.

When volcanoes erupt, they frequently lift large plumes of ash and dust thousands

of feet into the atmosphere. To a pilot, the ash and dust can resemble regular

clouds; however, if a plane flies into that ash plume, the engines will fail.

“Especially in volcanically active remote areas over which planes fly,

we’d like to work out a system to warn pilots of eruptions to divert them

around the ash clouds,” Bass says.

Seismic sensors note any rumbling in volcanoes. But rumbling does not necessarily

mean there is an ash release, Garces says. Currently, scientists work with airline

companies to divert planes around any rumbling volcano, but diversions can be

costly. “And much of the time, those are false alarms,” Bass says.

If infrasound is in place, the scientists think they can detect the atmospheric

disruption from the ash clouds and give the airlines precise rerouting information.

This project is in its infancy, Bass says, but the scientists hope to have sensors

in place near some active volcanoes to test their theory by the end of this

year. Right now, they are working with the U.S. and Canadian volcanic ash warning

centers to get the project off the ground. It is an exciting application, Garces

says, in which scientists can contribute to society.

“All of these projects are fascinating,” Garces concludes. “We

are just at the christening stage of infrasound, where we were with seismic

technology 30 years ago. By working with the existing seismic, satellite and

other observation networks, this technology has endless possibilities for teaching

us about the world.”

Sever

is a staff writer for Geotimes.

Links:

"Today's volcano risks,"

WebExtra Geotimes, May 24, 2004

Volcanic

Ash Conference

Back to top

The IMS

infrasound network will eventually contain about 60 stations somewhat evenly

distributed around the world, but it is only about one-third complete right

now, Garces says. “We hope it’ll be all up and running in the next

couple of years,” he says, “but that might be a little optimistic.”

Nevertheless, the scientists are already recording more information than they

can comprehend, he says.

The IMS

infrasound network will eventually contain about 60 stations somewhat evenly

distributed around the world, but it is only about one-third complete right

now, Garces says. “We hope it’ll be all up and running in the next

couple of years,” he says, “but that might be a little optimistic.”

Nevertheless, the scientists are already recording more information than they

can comprehend, he says.

Hedlin, Garces

and Bass work on a number of applications in concert, although each has their

own pet project. Hedlin pays close attention to storms in the Pacific. Garces

concentrates on infrasound emitted from the constantly erupting Hawaiian volcanoes

as well as sounds of the ocean. Bass focuses on using infrasound to create a

3-D image of the internal structures of the atmosphere (tomography). Together,

all three scientists are developing a project that uses infrasound to create

a volcanic ash warning system for airplanes.

Hedlin, Garces

and Bass work on a number of applications in concert, although each has their

own pet project. Hedlin pays close attention to storms in the Pacific. Garces

concentrates on infrasound emitted from the constantly erupting Hawaiian volcanoes

as well as sounds of the ocean. Bass focuses on using infrasound to create a

3-D image of the internal structures of the atmosphere (tomography). Together,

all three scientists are developing a project that uses infrasound to create

a volcanic ash warning system for airplanes.