|

FEATURE

Beer or Biofuels

Megan Sever

Beer and other foods are costing more — but are biofuels really to blame?

Crops by the numbers Print Exclusive

© 2007 Jason E. Kaplan |

| Beer, with its plethora of varieties and flavors — showcased here at the Great American Beer Festival in Denver, Colo. — has perhaps never been more popular than it is now. |

It’s Friday night and the end of another tough week. I wander into my local brewpub and order a pint of IPA. I throw a few bucks on the counter — enough for the pint and a tip — and meander through the crowded bar back to my table. I hear the bartender say, “Hey, you owe me another buck.” Perplexed, I turn around and inquire, “I thought it was $3?” He says, “Beer prices rose again. It’s all that darn biofuels production that’s increasing prices.” I pay the bartender and walk away, sipping my brew and pondering: Are biofuels really boosting beer prices? And how will that affect my beer budget?

News stories this spring have reported that food prices are higher than ever because corn and soybeans grown for biofuels have supplanted food crops such as wheat — and corn that was previously meant to be food is now going into biofuels. Beer, reports have said, is also getting pricier because farmers are planting biofuels crops instead of barley and hops, the two primary ingredients in beer.

Globally, grain stocks are at their lowest in 30 years, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. For four of the last five years, world grain consumption has outpaced production. Food inflation is rising at alarming rates, prompting riots in parts of Asia, Africa and the Caribbean and even prompting some U.S. stores, such as Costco, to impose purchasing limits on rice and other foods that are in short supply globally. In late April, the U.N. World Food Programme even called the high food prices “a silent tsunami” that threatens more than 100 million people. Biofuels have been taking the brunt of the blame for these issues.

But is the alternative fuel actually to blame? No — and yes. Experts say it’s the simple economics of supply and demand: General market forces and bad weather during growing or harvesting seasons are causing supply shortages. Meanwhile, demand for food is at record highs, thanks in part to economic growth in developing countries, and to a much lesser extent, growth in the biofuels sector. Record-high energy prices, in turn, are also affecting food prices and supply and demand. Together, these factors lead to a very tight market where any scarcity — real or perceived — can cause sudden demand spikes, supply shortages and thus price spikes. So in a roundabout way, biofuels could be somewhat responsible for causing beer prices — and food prices — to increase around the world.

Photo by Stephen Ausmus/USDA ARS |

| USDA Agricultural Research Service geneticist John Henning (left) and Anheuser-Busch agronomist Scott Dorsch examine and smell hop cones for quality and aroma characteristics. |

But for beer, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) statistics show that it is less about biofuels production than about market economics. After years of surplus and low prices, supplies of key ingredients for beer are down this year and demand is up; hence, prices are going up.

Yum, beer

It would be hard to find a time in history when beer, especially independent craft brews, was more popular than right now, says Julia Herz, a spokesperson for the Brewers Association based in Boulder, Colo. Despite losing some of its U.S. market share to wine in recent years, beer production rose more than 17 percent globally between 2002 and 2006, and craft brews are up more than 30 percent, according to the 2007 Brewers Almanac. In 2006, craft brewing grew 12 percent by volume and 16 percent by sales. That pattern continued in 2007, Herz says. “It’s an exciting and fun time for beer,” she says. “We’re seeing far more flavorful, fun and diverse beer out there on the market because it’s in such high demand right now.” People are clamoring for more styles and more flavors, she says. But whether the double-digit growth the industry experienced in 2006 and 2007 will continue is anybody’s guess.

Craft brews now make up nearly 6 percent of beer sales in the United States, accounting for $5.7 billion in annual sales, according to the Brewers Association. Out of 1,449 breweries in the United States in 2007, 1,406 are craft brewers. And craft brews have a far greater market share in particular regions, such as the Rocky Mountain West and the Pacific Northwest. Oregon alone accounts for 60 individual brewing companies and 82 brewing facilities, according to the Oregon Brewers Guild. Portland, the state’s largest city and the 23rd largest metropolitan area in the United States, has more breweries than any other city in the world. It is a good time to be in the beer business, says Brian Simpson, a spokesperson for New Belgium Brewing Co. Inc., in Fort Collins, Colo., which is the third largest U.S. craft brewer. Costs of production are rising, he says, but demand is increasing 10 to 12 percent each year.

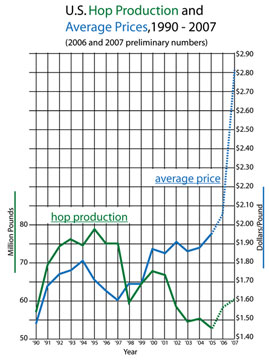

chart adapted from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service |

In addition, the market is moving toward “extreme beers” — beers that have more hops, greater bitterness and a high alcohol content, says Ashley Johnston, communications manager at Alaskan Brewing and Bottling Company in Juneau. Companies are responding by offering more varieties of beers with premium ingredients, adds Marcy Larson, co-owner of Alaskan Brewing.

Since 2004, dollar sales by craft brewers have increased 58 percent, according to the Brewers Association. This correlates with the growing American trend of buying local products, says John Ikerd, an agricultural economist at the University of Missouri in Columbia. There’s “a growing rejection of industrialized society,” he says, and beer is certainly not immune to that trend. Indeed, craft beer demand is showing “no sign of decreasing,” Herz says.

Hops and Barley

The demand for hops is about 10 to 15 percent higher than the supply, Herz says, driving prices up 500 percent in just the last few months. Barley is also in short supply: Consequently, prices have increased 40 to 70 percent over the same time period. Those kinds of price increases and tight supplies “affect everyone, from your local brewery to the Anheuser-Busch’s of the world,” says Joe Casey, assistant brewmaster at Widmer Brothers Brewing Company in Portland, Ore.

Besides water, hops and barley are the two primary ingredients in beer. Hops are flowers grown almost exclusively for beer. They are responsible for beer’s flavor and frothy head and also act as a preservative. Different varieties bring varying flavors and aromas, from citrus to spice to earthiness. People have been growing hops for beer since at least A.D. 736 in Europe and since 1629 in North America.

Stephen Ausmus/USDA ARS |

| Lupulin glands inside a hop cone produce the acids that give different varieties of hops different flavors. |

Hops only grow in a few countries. The United States contributes about 31 percent of the world hop crop and Germany contributes about 34 percent, according to the International Hop Growers Convention. Australia, Canada, China and several European countries make up the rest of the crop. In the United States, 70 percent of hops comes from the Yakima Valley in Washington. Because the crop grows in so few places, problems such as a drought or a flood can wreak havoc on the market. And that is precisely what happened in 2006 and 2007.

For the last two decades or so, farmers produced more hops than brewers needed, and brewers, merchants and growers ended up with large stockpiles of the crop, says Nadia Urvina of HopUnion, a major hops distributor in Washington. With such high supplies, crop prices were exceptionally low. “The [hops] industry has been operating at a loss for a decade-plus,” says Ann George, a spokesperson for the Hop Growers of America and the Washington Hop Commission. That knocked many farmers out of the business, she notes. In 1978, more than 2,000 farms grew hops in the United States. Thirty years later, only 45 hop farms remain. Globally, hop production has fallen more than 36 percent since 1996, with acreage dropping more than 44 percent. Yet beer production is up more than 58 percent globally in that same period, according to Hop Growers of America.

This shortage in the actual suppliers of hops coincided in 2006 with weather problems in the major hop-producing regions. Many U.S. crops did not reach expected yields due to a heat wave in the Pacific Northwest; China’s harvest was lower than predicted due to unusual weather and a pest and disease infestation; and floods and storms damaged crops in the Czech Republic, Germany, Poland and Slovenia, where a single tornado destroyed 40 to 50 percent of the year’s crop, according to the International Hop Growers Convention. Furthermore, Australia’s worst drought on record affected its crop.

Stephen Ausmus/USDA ARS |

| At the hop breeding facility in Corvallis, Ore., USDA Agricultural Research Service geneticist John Henning (foreground) and Oregon State University research associate Shaun Townsend are testing a new technique — growing hops on lower trellises than normal — which could lower labor costs by as much as 30 percent. |

The result is that current U.S. hop stocks are down 6 percent from 2007, according to USDA. Moreover, stocks held by brewers are down 14 percent. It may be that some farmers who once grew hops now are growing other crops — for biofuels or not — but it is more likely that the farmers were forced out of the business by the low prices a decade ago. Still, “the bottom line is that not enough hops are being grown today to satisfy the needs of brewers,” Urvina says.

Though the barley market was also exceptionally tight in 2006 and 2007 — the world barley market has the lowest stock-to-use ratio in more than 20 years — it is almost entirely driven by weather, considering production and acreage have actually increased in recent years, according to USDA. Barley is used to produce malt, the syrup that flavors beer. Barley grows in more places than hops, but it is also used in other products, such as malt vinegar and as a feedstock for animals, especially when corn prices are high. The drought in Australia and storms in Europe that damaged hops stocks in 2006 and 2007 also reduced barley yields by 40 to 60 percent. Combine all of those factors and you have high market prices, Ikerd says.

Due to scarcities across the board, most commodities exhibit a razor-thin margin between supply and demand right now. “We’re seeing the fragility of the balance between scarcity and surplus,” Ikerd says. “If you take 20 percent of the corn that had previously gone into the food supply chain and put it into something else, it produces a major shock to the system,” especially when you then shift some of the barley that had gone to beer production to feedstock instead. “On the surface, the shift seems pretty minor, but if you then add in a drought or a severe storm that knocks out a crop, the shift becomes major,” he says. Neither the barley nor the hops markets can afford to have any major crop failures in 2008.

The good news for brewers is that with the high prices, farmers are beginning to replant hops, George says. In 2007, farmers in the Pacific Northwest planted 2,000 new acres of hops, and they will plant some 6,000 to 8,500 new acres in 2008, she says. The bad news is that while some hops varieties take only a year to come online, others take up to three years. “It’s definitely going to be a tight market for at least another couple years,” Urvina says. Eventually, though, the market will catch up, George says. Indeed, following the surplus of a decade ago, it is not surprising to see a scarcity arise now, Ikerd says. The markets tend to be cyclical, he says. When prices go up as high as they are right now, there tends to be a big increase in production, which if not well controlled, can lead to another surplus and a sharp decrease in prices. “We want to reach an equilibrium where supply roughly equals demand,” George says. “Certainly there will be a year-to-year fluctuation with weather and other forces,” she says, “but we need to ensure reasonable prices for everyone, to ensure that growers can make a livelihood and brewers will buy the product and the system balances long term.”

Prices

Add human nature — and our innate ability to panic at the thought of scarcity — to the supply-and-demand equation and you will see prices increasing 500 percent in a few months. If a brewer has long-term contracts in place that lock in supply (hops, barley or otherwise) at a certain price, that further tightens the markets on other brewers that did not have such contracts. Furthermore, add in the fact that the euro is far stronger than the dollar right now — and thus European brewers can afford to pay far more for American hops than American brewers can — and the market gets even tighter, Urvina says.

photo courtesy of Alaskan Brewing and Bottling Company |

| Alaskan Brewing and Bottling Company, like many craft brewers, is facing cost increases. |

No one is immune. Whether companies have long-term or short-term contracts, or produce large amounts of beer or small, when prices spike and shortages occur, everyone is affected, says Larson of Alaskan Brewing. “Like all brewers, we are experiencing cost increases due to the rising prices of brewing ingredients,” adds Michael Owens, vice president for business operations at Anheuser-Busch. However, because craft brewers tend to make more flavorful beers that therefore require more ingredients (more hops and malted barley), they tend to be hardest hit by the price increases, Herz says.

To that end, everyone is thinking about efficiencies, Larson says. And to a degree, they are forced to pass some of the increased costs on to the consumer, she says. Alaskan Brewing had to increase its prices by $1 per six-pack over the past two years, she says. “That’s really painful, but it’s a reality. All craft brewers are wrestling with the same thing — how to keep up the quality of the product and the taste without having to raise prices too much.” Many other craft brewers have had to raise their prices as well, from 50 cents to several dollars per six-pack, and between 25 and 50 cents per pint, served at a bar. Furthermore, keg prices have also risen significantly, from $20 to $50 per keg, according to a manager at The Bier Stein in Eugene, Ore. Moreover, it’s not just barley and hops that impact beer makers — it’s also the price of energy, metals, glass and more, Herz says. However, the beer industry as a whole has only seen a 0.02 percent increase in pricing between April 2007 and April 2008, she says. That indicates that although many craft brewers are increasing their prices a bit, she says, there don’t seem to be dramatic increases. Whether that statistic holds true for the rest of the year remains to be seen.

USDA ARS |

Fortunately, “I haven’t heard any brewers saying that things are so bad that they won’t be in business next year,” Herz says. However, she says, it is possible that particular varieties of beer may not be produced or brewers may change their recipes a bit until the market evens out. “Right now, a lot of brewers are still working to get what they need, and a lot of brewers are having trouble getting the particular [varieties of] hops they want” for particular beer flavorings, she says. Some brewers are even trading one variety for another: For example, Boston Beer Company (maker of Sam Adams, and the number one craft brewer in the country) is releasing some of its hops varieties to smaller brewers. “There’s a lot of camaraderie among the craft brewers,” Herz says.

Long-term contracts insulate brewers from the worst of the shortages, Larson says. But even if a company has a large inventory or a long-term contract, there may be shortages of particular varieties of hops needed for a particular beer. “And I think it might get worse,” says Casey of Widmer. “I think in coming years we’re going to see less diversity of hops varieties, which will obviously affect the beer flavors and aromas. Down the line, it may become more challenging for brewers to develop a new flavor of beer,” he says. “We’ll see.”

In January, The Bier Stein raised its microbrew pint prices by 50 cents a pint, after the brewers raised their prices. Most of the other bars in Eugene — a college town home to several of its own breweries — raised their prices as well. Nevertheless, sales are actually at record levels, especially for microbrews. Several brewers, including Alaskan’s Larson and New Belgium’s Simpson, say that they don’t anticipate a significant drop in demand due to across-the-board higher prices for the product. However, the economy is tighter all around right now, Larson notes, and everyone will have to be more frugal about everything in their lives. No one knows just how that will play out in the beer world.

“But,” she asks wryly, “are you going to stop drinking good beer?”

On that note, I’m going to pour myself a cold one and watch some baseball.

Subscribe

Subscribe