|

FEATURE

Salt of the Earth

Cassandra Willyard

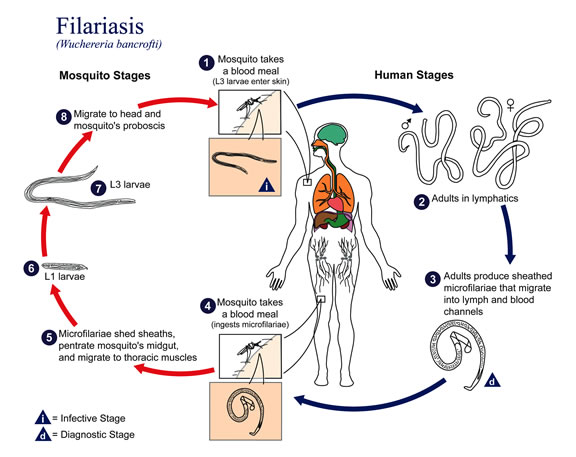

The life cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti

Salting the daily bread Print Exclusive

CDC/Dr. Mae Melvin |

| A photomicrograph of Wuchereria bancrofti in a blood smear. |

In the tiny South American nation of Guyana lives a problematic parasite called Wuchereria bancrofti. This thread-like worm hitchhikes from person to person in the bellies of mosquitoes and lodges itself in the delicate vessels of the body’s lymphatic system. There it wreaks havoc.

The lymphatic system drains and filters the body’s fluids. But when tangled nests of worms infest the vessels, fluids can’t flow properly. Instead, they pool within the body, causing an infected individual’s limbs or genitals to swell and stretch. The disease is called lymphatic filariasis, but the symptoms have their own names, such as elephantiasis or the more colloquial “Big Foot.”Filariasis not only disfigures, it also disables. Some Guyanese are unable to walk or even stand, let alone work. And then there’s the stigma that goes along with having feet so large that no shoe will fit. (Men have been known to abandon their wives for less.) “These people become total social outcasts,” says Robin Houston, an international public health consultant who has worked in Guyana. “They can’t really do anything.”

Filariasis is difficult to treat, but easy to prevent. A cheap drug called diethylcarbamazine — DEC for short — kills the worms before they can cause damage or spread. Used consistently, it can stop transmission of the parasite. Distribution, however, is a problem. Guyana’s roads can be muddy and treacherous. Moreover, even in areas where the roads are passable, the country doesn’t have enough health workers to ensure that everyone takes the medication. So instead of handing out pills, the government decided to spike the salt supply.

Whoever first said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” likely wasn’t thinking of salt. Yet the saltshaker has become one of the most powerful weapons in the public health arsenal. “Salt is an ideal vehicle,” says Trevor Milner, an international public health consultant based on St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. “It’s cheap and it’s accessible to everyone.”

An ounce of prevention

The idea of putting additives in salt to promote health dates back to the 1920s, when salt suppliers in the United States and Switzerland began fortifying their salt with iodine. The measure was intended to combat a condition known as “goiter” — a swelling of the thyroid, a gland that sits just in front of the windpipe.

CDC |

| This man’s swollen legs are caused by a parasitic worm that invades the body’s lymphatic system. |

Goiters have plagued humans for at least several thousand years. As early as 2,700 B.C., Chinese emperor Shen Nung allegedly prescribed seaweed, now known to be rich in iodine, as a treatment. Although not especially painful, large goiters can interfere with breathing and swallowing. And we now know that they’re only a symptom of a much larger problem. “The goiter is the visible manifestation” of iodine deficiency, says Richard Hanneman, president of the Salt Institute in Alexandria, Va.

Iodine, a purplish-brown element that is rare in Earth’s crust but common in seawater, is essential for all life. Humans need about 150 micrograms each day. Most of that gets taken up by the thyroid and is used to make hormones that regulate metabolism. If the body lacks iodine, the thyroid doesn’t have the raw materials it needs to make these hormones. To compensate, the gland begins to grow, forming a goiter.

In the United States, few realized just how common goiters were until doctors began examining men drafted to serve in World War I. Simon Levin, a physician in Lake Linden, Mich., found that 30 percent had visibly swollen thyroids: Another 2 percent had goiters large enough to prevent them from serving. In fact, more men in northern Michigan were disqualified from military service because of goiters than any other medical condition. The state was in the middle of a swath of land that would become known as the “goiter belt.”

Before people got iodine from salt, they got it from their food. Foods pick up iodine from the soils where they grow (or, in the case of seafood, from seawater). But the element is unevenly distributed across Earth’s landmasses. Inland areas and mountainous regions tend to have iodine-poor soil. And because historically most of the food consumed was locally grown, the inhabitants of iodine-poor regions tended to develop iodine deficiency, and goiters.

Although health officials didn’t know it at the time, iodine deficiency also leads to much more serious problems. Expectant mothers who don’t get enough iodine can have children who are mentally and physically stunted — a condition known as “cretinism.” Even moderate iodine deficiency in the mother during pregnancy can reduce her child’s IQ by 10 to 15 points. Before iodized salt was introduced in 1978, the village of Jixian in northeast China was so iodine deficient, it was known locally as the “village of idiots.”

Dave Price |

| Iodine deficiency has caused this Cameroonian woman’s thyroid to swell, producing a goiter. |

Doctors had been treating iodine deficiency with iodine syrup, but health officials wanted to prevent goiters, not just treat them. Obviously going door to door with bottles of iodine syrup wasn’t going to work. They needed to find a way to mass distribute iodine that would be economical and efficient. Salt was an obvious choice — it’s cheap, it’s easy to transport, it doesn’t spoil and everyone uses it. Salt is the “food that comes closest to being universally consumed,” says Venkatesh Mannar, executive director of the Canada-based Micronutrient Initiative. And the risk of overdose is minimal because everyone eats a predictable amount, between five and 15 grams each day: The same can’t be said of other commodities, such as sugar or flour.

What’s more, iodine occurs naturally in some salt deposits. In fact, until 1900, salt mined and used by residents in the Kanawha River Valley in West Virginia contained trace amounts of iodine. As a result, goiters were rare in the region. But then, the crude brown local salt was replaced with clean, processed salt mined in Ohio and Michigan. By 1922, 60 percent of schoolgirls surveyed in Charleston and Huntington, W.Va., had enlarged thyroids.

Iodized salt first appeared on grocery store shelves in Switzerland in 1921 and in the United States in 1924. In Michigan alone, the prevalence of goiter dropped more than 75 percent over the next two decades. Iodized salt didn’t begin making its way into developing countries until the 1980s. With support from UNICEF and the World Health Organization, however, it spread remarkably fast. Globally, the percentage of people with access to iodized salt has climbed from 20 percent in the mid-1990s to about 70 percent today. “It’s a great public health success,” Houston says.

Stacking the DEC

Salt iodization paved the way for other additives. In 1955, Switzerland began adding fluoride to its salt to prevent dental cavities. Soon after, people began to experiment with more controversial, human-made additives — first, the anti-malarial medication chloroquine, and later, DEC.

Lymphatic filariasis isn’t limited to Guyana. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 120 million people worldwide are infected with Wuchereria bancrofti or one of the other two worms that cause lymphatic filariasis in Africa, South America and Asia. Of those, 40 million have been disfigured or handicapped by the disease. The goal, as outlined by the World Health Assembly in 1997, is to eliminate lymphatic filariasis by 2020 — no easy feat given that the disease persists in some of the most isolated and impoverished regions of the world.

To combat filariasis, health workers usually prescribe DEC tablets. Each year, they try to get as many people in the affected areas to take a dose of DEC (combined with another drug) as possible. But the intervention is expensive and time-consuming. Guyana doesn’t have enough health workers to carry the tablets door to door. Put the DEC in salt, however, and it distributes itself.

photo courtesy of Patrick Lammie |

| Haitians harvest salt by letting seawater evaporate from large shallow pools called salt pans. |

There are other benefits to using salt. Large doses of DEC can cause side effects in those who are infected. The medicine kills microscopic worms in the bloodstream and a massive die-off can sometimes cause memorable symptoms — headaches, fever and nausea. People who agree to take the pill one year, might not the next. “I think it’s very difficult to mobilize an entire population to take a pill once a year,” Houston says. But the dose of DEC people get in the salt is so low “that it’s not associated with the same side effects,” says Patrick Lammie, an immunologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Ga.

The idea of adding DEC to salt to eliminate filariasis was the brainchild of physician Frank Hawking, father of famed astronomer Stephen Hawking. In 1967, Hawking published a paper in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization showing that DEC stays stable and potent in salt, even after being cooked. He and a colleague even tested DEC salt on mental patients and prisoners in Recife, Brazil, with good results. But it wasn’t administered on a large scale until the 1970s, when China began using it as part of a campaign to eliminate filariasis. “They were the ones that really showed that you could use this as a public health intervention,” Lammie says. “Over 200 million people in China received DEC salt.”

The results were impressive. In one county in Shandong Province, DEC salt reduced the rate of infection from 9 percent to less than 1 percent in as few as six months. After six years, doctors could not find anyone who was infected. Before the initiative, an estimated 31 million people in China were infected. As of 1994, transmission had ceased. In 2006, the World Health Organization declared China officially free of lymphatic filariasis.

But it’s unclear whether the strategy can work as well in democratic nations, Milner says. China’s situation was unique, he says. “They were very much a command and control society.” They mandated that certain regions use DEC salt rather than giving people an option. As a result, “they were able to achieve very high levels of population coverage,” Lammie says.

Success has proven more difficult to achieve in other countries, where officials must convince salt producers to make DEC salt, shopkeepers to carry it and consumers to buy it. “The question that hasn’t been fully answered is whether this kind of strategy can work in open markets,” Lammie says. Fortifying salt with an essential element is perhaps more socially acceptable than fortifying it with a drug. Guyana, which introduced DEC salt in 2003, is a test case. And things haven’t been going well.

The Micronutrient Initiative |

| People in Ghana use this machine, developed by the Micronutrient Initiative, to iodize salt. |

One of the first problems arose even before DEC salt was on the shelves. Back then, most salt suppliers in Guyana sold salt in 50-kilogram bags. “The shopkeepers would parcel this out,” putting it into smaller unmarked bags, Milner says. To help prevent contamination and accidental spills, Milner and his colleagues asked the supplier to put the salt in individual labeled bags. They wanted to “upgrade the packaging and presentation,” he says. There was just one problem: On the label was a list of ingredients that included an FDA-approved anti-caking agent called potassium ferrocyanide.

The chemical had been in the salt for years, but seeing cyanide on the label gave Guyana’s residents pause. Their trepidation wasn’t all that surprising given that hundreds of followers of cult-leader Jim Jones died in Guyana in 1978 after drinking cyanide. “When they saw this name, the negative associations took place,” Milner says.

The next obstacle came soon after the salt went on sale. DEC salt should be white, but this salt had turned blue, says Nicola Butts, who works for Guyana’s Ministry of Health. It’s not clear exactly what the problem was (Milner says acidity, Butts says moisture), but according to Milner, the discolored salt was “off-putting.”

Once officials finally had coaxed people into trying DEC salt, they ran into supply problems. Guyana imports all its salt from neighboring countries. DEC salt comes from a single salt producer in Jamaica. In 2004, Hurricane Ivan destroyed the facility, halting production. By the spring of 2005, the country had run out of DEC salt. Even in fair weather, however, supplies can be unstable. “Guyana is fairly isolated in the trade networks,” Milner says. “It’s at the end of the line and transport is expensive.” Often the importers will wait until they can bring in an entire shipload of salt before restocking supplies. In the meantime, the salt supply dwindles. “In the case of the DEC salt, it ran out,” Milner says. The other importers took advantage of the opening and flooded the market with untreated salt. As of 2005, only half of the population used DEC salt and only a third of the shops carried it.

© Agron Dragaj 2008. |

| Workers transport salt from the seawater salt pans of Petchaburi, Thailand. Sea salt production remains a small-scale artisan industry in Thailand, with several hundred producers. |

According to Butts, most of these problems have been resolved and she and her colleagues are making headway — mainly through public education. People used to think filariasis was hereditary, Butts says. “But now they know that it’s caused by a mosquito and that anybody can get it.” They are also starting to understand that DEC can protect them from the parasite. Guyana even has a catchy slogan: “Get on the BUS — Buy DEC salt, Use DEC salt and Share the information with family and friends.” And now DEC salt comes fortified with iodine and fluoride. “They are responding to it positively,” Butts says. But Guyana still has a long way to go before the disease is eradicated, as does the rest of the world.

Worth its salt?

Whether DEC salt will continue to play a role in the eradication effort is not entirely clear. Guyana is one of only a handful of countries that are using DEC salt. The fact that the strategy hasn’t been “a roaring success,” Lammie says, might mean it will be one of the last. “It’s an open question at this point whether Guyana can stick to this strategy. The fact that it hasn’t been a quick fix probably will lead other countries to be more cautious,” he says.

In retrospect, Guyana may not have been a good place to test DEC salt, Houston says. In fact, the country never even had a successful iodization program in place. “We had a number of things that conspired against us,” he says.

Despite the disappointments, Milner, Lammie and Houston argue that DEC salt can succeed. They point to China’s achievement and the mass distribution of iodized salt as proof of concept. “It seems so obvious that once you can get this thing working, it will eradicate the disease at a lower cost and in a shorter period of time,” Milner says. “The big ace card that we hold is that it works.”

The life cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti

|

Subscribe

Subscribe