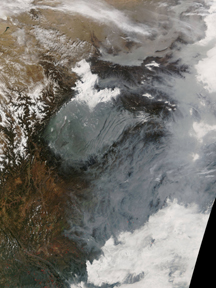

China

has had fewer days with cloud cover over the past half-century, according to

new weather station data. At the same time, however, the region has cooled and

evaporation has decreased — suggesting instead the presence of more clouds,

which reflect solar rays and their heat. Researchers analyzing the new data

speculate that increases in pollution may be the culprit behind the paradox.

China

has had fewer days with cloud cover over the past half-century, according to

new weather station data. At the same time, however, the region has cooled and

evaporation has decreased — suggesting instead the presence of more clouds,

which reflect solar rays and their heat. Researchers analyzing the new data

speculate that increases in pollution may be the culprit behind the paradox.

A team led by Yun Qian of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland,

Wash., looked at data taken from 1955 to 2000 from 537 weather stations scattered

across China. They determined that on average, differences between night and

day temperatures and the amount and duration of sunshine in China had decreased

around 2 percent every decade, which would suggest an increasing trend in cloud

cover. But, the team wrote in Geophysical Research Letters on Jan. 11,

human and satellite observations told a different story: Cloud cover decreased

slightly over that time period. Haze remained, however, measured by the stations

as overcast days.

China’s emissions of aerosol particles that create haze increased until

the mid-1990s, according to state records, and have seemed to level out since

then. Aerosol particles have properties that allow them to both scatter and

absorb solar radiation, depending on whether they are made of sulfate (which

reflects it) or soot (black carbon, which absorbs it). The “mismatch”

between cooling and increased smog, the team says, “reminds us of the complexity

of aerosol composition and mixing.”

In this case, the haze seems to have reflected more solar radiation, preventing

it from reaching the ground. Less heat on the ground would decrease the evaporation

of soil moisture, which contributes to cloud formation.

“The key in this case was the fact that the cloud fraction was decreasing

simultaneously with solar radiation,” which gives the new report a “unique

angle” on describing aerosols over China, says Mark Jacobson, an atmospheric

scientist at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. Jacobson hazards his own

guess as to why aerosols might be further reducing solar radiation in the area:

As the particles absorb heat in the atmosphere, the warmer temperatures keep

water from depositing on clouds, as relative humidity increases. This lack of

water leads to smaller spread out clouds — in effect, blocking more solar

radiation.

Despite their speculation that smog is responsible, the researchers wrote that

people “cannot expect a simple correspondence between pollutant emissions

and solar radiation on annual or even decadal timescales.” Still, Qian

says that smoggy regions experienced a slight cooling effect, noting that the

particle pollutants possibly offset the background temperature signals from

global warming. “The emission issue is very difficult to predict,”

he says, depending on China’s future coal use and energy production, as

well as environmental protection policies and the adoption of sulfur emission

controls.

The research is “a very clever study showing the impact of increased aerosol

air pollution on climate in China — simple measurements showing profound

effects,” says Russell Dickerson of the University of Maryland in College

Park, with results consistent with satellite observations and past studies.

Dickerson says that particulate matter in the atmosphere “probably [has]

large-scale impacts” on chemistry and air quality. He sees the work as

support for a “call for action to implement methods for sustainable development

in Asian industry, transportation and agriculture.”

Naomi Lubick

Back to top

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |