|

EDUCATION & OUTREACH

Bringing the Mars Science Laboratory

into the Classroom

Nicole Branan

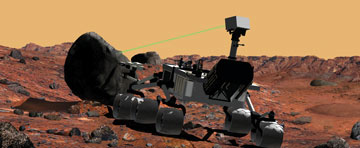

NASA/JPL-Caltech |

| Mars Science Laboratory's "ChemCam" will test Martian rocks for chemical clues to life. |

Mars is the second-heaviest-trafficked planet in our solar system (after Earth). The exploration rovers Spirit and Opportunity have been roaming the dusty, deserted Martian landscape for the past four years and NASA plans to launch their successor, the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), in 2009. But exactly where on the red planet’s nearly 233-million-square-kilometer surface the MSL will touch down is still unknown. To find a location that’s both scientifically interesting and geologically accessible, scientists around the world have been poring over the available data. Even students are getting in on the action.

Marion Anderson of Monash University in Australia, who has been participating in NASA’s MSL site selection process, made studying and evaluating possible landing sites for the 2009 mission an optional class project for her geology undergraduate students. Working on a hands-on assignment like this helps students get engaged in science, she says.

“I have found it challenging and exciting to explore new realms of our neighboring planets,” says Daniel Saunders, one of the students who participated. The assignment also provided an opportunity for students to get involved in actual research, Anderson says. “This was the lowest-cost, easiest-access project I could give my students that would allow them to get involved in real research. All they needed was time, a good computer and Internet access.” NASA and other Web sites contain literally hundreds of thousands of images of the Martian surface that are available for public access, Anderson says, adding that many of them have only been viewed by a few people.

Anderson, who ran a similar project with her students for the Mars Exploration Rover landing site selection in 2002, says the starting point for the project was a one-hour seminar during which she introduced the mission’s goals. Students who were interested in researching potential landing sites could then select one of the top 13 sites that had been proposed during previous MSL meetings. In self-organized teams, the students tried to learn everything they could about the individual sites and determine how suitable the sites were as MSL landing locations. Every two weeks, Anderson and the students got together to check on their progress and discuss problems. Students who participated in the project received no extra credit for it. “They were involved purely for the sake of being involved,” Anderson says.

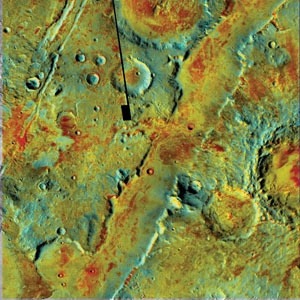

NASA/JPL/Arizona State University |

| Nili Fossae Trough is one of the many sites NASA is considering as a landing site for the Mars Science Laboratory. |

The MSL mission’s main goal is to find out whether Mars ever was, or still is, an environment able to support microbial life. The design and capabilities of the MSL rover are crucial to the success of the billion-dollar mission, but whether or not it will turn up clues about past or present life will ultimately depend on whether the rover lands in the right location. “That’s why the landing site selection is so important,” Anderson says.

Searching for areas that could harbor signs of life on a planet millions of kilometers away is like a treasure hunt without a map. About a dozen previous Mars missions have beamed a voluminous collection of photos of the planet’s surface down to Earth, but none of them contain the proverbial “X” that marks the best spot. Thus, Anderson’s students started where the scientists started — searching the surface for indications of past water or evidence of the type of sediments and rocks, such as clays, that could store and retain organic chemicals.

But the sites’ topographies were equally important because there is some terrain on Mars that the MSL rover can’t handle. NASA plans to let the spacecraft descend through the planet’s dusty atmosphere on a parachute and then lower the rover to the surface on a tether. While this procedure is much more precise than the one employed for Spirit and Opportunity, which smashed onto the planet’s surface wrapped in airbags and bounced for a bit before coming to a stop, the MSL could end up anywhere within a 40-kilometer-diameter area. The MSL rover’s limited capability to crawl over obstacles no higher than 75 centimeters put constraints on possible landing sites.

“The students had to find out if there were too many boulders, whether the rover could navigate to the target area, or whether it was blocked by sand dunes or cliffs,” Anderson says. Each group gathered data from a variety of different sources, including visual images and elevation data acquired by the Mars Orbital Laser Altimeter. From that, she says, they synthesized a coherent view of what the data were actually saying. Their analysis led them to come up with a list of top five sites, two of which are now among NASA’s finalists.

Besides teaching students how to gather and evaluate data carefully, the project also emphasizes teamwork. “One of the things I learned was the importance of working with a team to work out problems and end up with a logical answer,” says James Ell, a student who participated in the project. Students also got a taste of life as a planetary geologist. “I would like to continue in this field,” Saunders says. Working on this project “has helped me make this decision,” he adds.

Anderson tracked the grades obtained by students who participated in the Mars Exploration Rover site selection projects through the subsequent years of their degree and saw that their grades were consistently higher than those of students who were studying identical subjects but had not participated. And surveys before and after each group’s involvement in the Mars Exploration Rover and Mars Science Laboratory sites found that students’ attitudes toward studying science in general had changed. Students valued the need for a strong education in mathematics, chemistry and physics more than they did prior to the project. “I think that participation in the project helps students gain a much greater appreciation for why we encourage them to stick with the hard science units in the first years of their degrees and they see that what they learn in them does actually have a useful role in later years of science,” Anderson says.

Students who worked on the Spirit and Opportunity landing sites several years ago chose Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum, the exact locations to which NASA ended up sending the rovers. It remains to be seen whether they’ll be as accurate this time around, when NASA chooses the sites for the MSL this spring, but Anderson is confident.

Subscribe

Subscribe