|

NEWS NOTES

Dust in the wind

Anna Gorbushina |

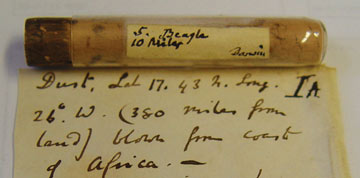

| A sample of Atlantic dust collected by Robert B. James and later sent to Charles Darwin. The handwriting below the vial is Darwin’s. |

On March 7, 1838, a dust storm engulfed an English ship sailing near the Cape Verde Islands off the western coast of Africa. According to a letter written by the ship’s commander, Lieutenant Robert B. James, the crew was nonplussed. But James saw an opportunity for the advancement of science. Using a wet sponge, he set about collecting samples of the dust “for the good of the Geologist.” More than a century and a half later, microbiologists are benefitting from James’ diligence too. New research shows that the dust traveled thousands of kilometers and still contains live bacteria and fungi, lending support to the idea that microbes can hitchhike their way across oceans on the tiny grains.

Each year, winds whipping over the Sahara pick up billions of tons of sand and dust. The vast majority comes from the Bodélé Depression, a sun-baked region once covered by Lake Chad. As the dust travels, the heavier particles fall out, raining down on West Africa. The finer particles, however, can travel much farther. Some scientists have speculated that these long-ranging dust clouds might spread disease. “About 20 or 30 percent of the organisms in dust clouds are pathogens to some kind of organism,” says Dale Griffin, a microbiologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Last year, William Broughton, a plant biologist at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, and his colleagues in Germany examined James’ antique dust samples to pinpoint the dust’s origin and to search for signs of life. Dust samples collected today would be contaminated with local microorganisms unless they were collected high in the stratosphere. By using James’ samples, the scientists ensured that “local contamination ceased in the nineteenth century,” Broughton says.

According to geochemical analysis, James’ dust is similar in composition to sands found in the Sahara today, Broughton’s team reported in the December issue of Environmental Microbiology. In fact, Broughton says it is “highly probable” that the dust came from the Bodélé Depression. The ancient lakebed, littered with the shells of long-dead sea creatures, is rich in calcium, as is the dust.

That means the dust traveled more than 4,000 kilometers before James collected it, and likely could have traveled farther. En route, the particles were exposed to dry air, harsh ultraviolet rays and extreme heat. Yet somehow life survived. When the researchers wet James’ dust and spread it out in Petri dishes, at least 12 identifiable species of fungi and 15 species of bacteria — including one that can cause food poisoning — began growing. “I’m not surprised,” says Griffin, who was not involved in the study. “Viable organisms have been recovered from mummies.” Not every species could be revived, however. Only those that form protective spores survived the trip and more than 100 years in storage.

Next, Broughton and his colleagues hope to compare James’ samples with current dust from the Bodélé Depression. Getting samples from Chad, however, is no easy task. “It’s a war zone,” Broughton says. That’s why he asked the Red Cross for help. So far, they have sent him nine samples of desert sand. He and his colleagues have already begun sifting through them to look for microbes. But, they haven’t yet found any cause for concern. “We have not found bona fide pathogens even in sand from densely populated areas,” Broughton says.

African dust can travel as far as the Caribbean and New Mexico, but don’t expect to hear news of a dust-induced epidemic anytime soon. The process has been going on for hundreds, if not thousands of years and most human pathogens are relatively fragile. Crops, not people, are at greatest risk.

Links:

"African Dust in America," Geotimes, November 2001

Subscribe

Subscribe