Geotimes

Travels

in Geology May 2004

Soaking up Glenwood Springs

Glenwood

Springs, Colo., is not a typical Western boomtown. Although silver and coal

mining brought some folks to the area in the early days, Glenwood's greatest

geologic asset is its hot springs. Today, the springs and vapor caves are still

the main attraction for visitors to this city, 150 miles west of Denver on Interstate

70. But there's much more to Glenwood Springs than soaking and sweating.

Glenwood

Springs, Colo., is not a typical Western boomtown. Although silver and coal

mining brought some folks to the area in the early days, Glenwood's greatest

geologic asset is its hot springs. Today, the springs and vapor caves are still

the main attraction for visitors to this city, 150 miles west of Denver on Interstate

70. But there's much more to Glenwood Springs than soaking and sweating.

Through the 19th century, Ute Indians considered the area's springs and vapor

caves a sacred healing site; each spring they returned to rejuvenate themselves

at Yampah, or Big Medicine. White men discovered the springs for themselves

in the 1860s and shared the belief that the springs could restore health. Investors

bankrolled an extravagant bathhouse including Roman vapor tubs. The resort attracted

royalty and politicians from around the world as well as ailing citizens, including

the gunslinging dentist and card dealer, Doc Holliday (who died in Glenwood

of tuberculosis in 1887).

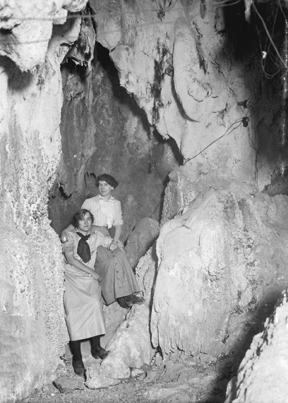

Glenwood Springs, Colo., is known

for its hot springs and caverns. Photo courtesy of Glenwood Hot Springs Lodge

and Pool.

Geologists are unclear on the source of the springs, but theories on its origin

include circulating groundwater and trapped volcanic heat. Whatever the origin,

the waters are abundant and hot: Flows send 2,700 gallons per minute to the

surface with temperatures up to 125 degrees Fahrenheit. Along the way, the springs

move through fault fractures in limestone deposited about 300 million years

ago, when Glenwood was an equatorial beach instead of in the heart of the Rockies.

Over time, the spring waters have dissolved the limestone and left behind minerals

to create layered ledges and terraces of travertine as well as the only natural

vapor caves in North America (all others are manmade excavations ).

Other

caves and sinkholes have also formed in these karst landscapes including Glenwood

Caverns, formerly known as Fairy Cave. Visitors to the caverns can wander 3

miles of known subterranean passageways and make their way almost 300 vertical

feet underground. Bold adventurers can sign up for private tours and throw on

headlamps and spelunking equipment to explore the stalactites and stalagmites

of the 60-foot tall Barn, as well as tighter crevices, if they can contend with

the claustrophobia.

Other

caves and sinkholes have also formed in these karst landscapes including Glenwood

Caverns, formerly known as Fairy Cave. Visitors to the caverns can wander 3

miles of known subterranean passageways and make their way almost 300 vertical

feet underground. Bold adventurers can sign up for private tours and throw on

headlamps and spelunking equipment to explore the stalactites and stalagmites

of the 60-foot tall Barn, as well as tighter crevices, if they can contend with

the claustrophobia.

For some open-air activity, head east out of town on Interstate 70 and drive

along the Colorado River through Glenwood Canyon. This was the last stretch

of the interstate highway system to be completed. Engineers built a series of

tunnels, bridges and viaducts to protect rock walls, cliffs and other natural

features. The construction, which cost $490 million (20 times the average cost

of an interstate project) has received numerous awards for its innovative design.

The eastbound trip through the 15-mile long canyon is a nearly comprehensive

journey 2 billion years back in geologic time to the Precambrian Era. The river

has eroded 2,000-foot walls of sedimentary rock, and fault lines are visible

along the cliffs where rock layers mismatch. The one confusing stop on this

journey is the "Great Unconformity," between the Precambrian rocks

and overlying quartzite, where a billion years of history is missing. Pull off

at Hanging Lake (Exit 125) and from the parking area look for the colossal pink

and gray boulders of Precambrian granite and schist that mark the missing time.

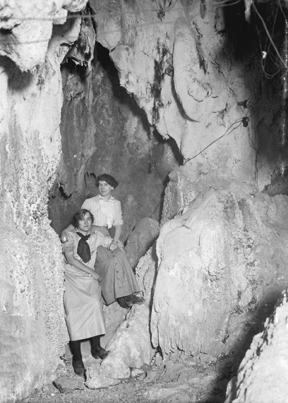

In this historic, circa 1900, black-and-white photo, two young women in Gibson-girl

outfits syand inside Glenwood Caverns, then known as Fairy Caves. Photo courtesy

of the Frontier Historical Society, Glenwood Springs, Colorado, Schutte Collection.

If you've got time — and the lungs and legs — take the short but

steep hike up to the lake. The Hanging Lake trail climbs 1,000 feet to a crystal

clear travertine basin fed by an impressive wall of waterfalls. Enjoy the cool

and raging mist of Spouting Rock before heading back down to the vehicle (and

be grateful that not all waters around Glenwood are 125 degrees).

Keep heading east on the interstate and, after Hanging Lake, you'll start moving

forward in time again. Where the canyon opens up again, the small town of Dotsero

sits below the cinder cone of a 4,000-year-old volcano. The eruption was Colorado's

most recent, and if you get permission from the Dotsero Block Company (which

makes cinder blocks from the cone debris), you can visit the site and look down

on the lava flows that pushed the river's course.

After all that spelunking, driving and hiking, you've earned a soak or a sweat.

Even though Glenwood Springs no longer resembles the sacred site of the Utes,

it remains a great place to revitalize both mind and body. The Glenwood Hot

Springs Lodge and Pool is still a resort; the Yampah Spa and Vapor Caves now

offer facials and massages. Close your eyes and take deep breaths while sitting

in the bubbling springs or steaming crypts, and it's easy to tap into the healing

powers.

Joshua Zaffos

Geotimes contributing writer

Links:

Glenwood

Hot Springs Pool and Lodge

Yampah

Vapor Caves and Spa

Glenwood

Caverns

Hanging

Lake

Read more Travels in

Geology

Back to top

Glenwood

Springs, Colo., is not a typical Western boomtown. Although silver and coal

mining brought some folks to the area in the early days, Glenwood's greatest

geologic asset is its hot springs. Today, the springs and vapor caves are still

the main attraction for visitors to this city, 150 miles west of Denver on Interstate

70. But there's much more to Glenwood Springs than soaking and sweating.

Glenwood

Springs, Colo., is not a typical Western boomtown. Although silver and coal

mining brought some folks to the area in the early days, Glenwood's greatest

geologic asset is its hot springs. Today, the springs and vapor caves are still

the main attraction for visitors to this city, 150 miles west of Denver on Interstate

70. But there's much more to Glenwood Springs than soaking and sweating.

Other

caves and sinkholes have also formed in these karst landscapes including Glenwood

Caverns, formerly known as Fairy Cave. Visitors to the caverns can wander 3

miles of known subterranean passageways and make their way almost 300 vertical

feet underground. Bold adventurers can sign up for private tours and throw on

headlamps and spelunking equipment to explore the stalactites and stalagmites

of the 60-foot tall Barn, as well as tighter crevices, if they can contend with

the claustrophobia.

Other

caves and sinkholes have also formed in these karst landscapes including Glenwood

Caverns, formerly known as Fairy Cave. Visitors to the caverns can wander 3

miles of known subterranean passageways and make their way almost 300 vertical

feet underground. Bold adventurers can sign up for private tours and throw on

headlamps and spelunking equipment to explore the stalactites and stalagmites

of the 60-foot tall Barn, as well as tighter crevices, if they can contend with

the claustrophobia.