Landscapes

fascinate Michael Collier, as do people and planes. He has built all three interests

into a surprising career as a professional photographer, geologist and medical

doctor. His work translates landscapes, photographed from the perch of his plane,

into geological stories from around the world for a broad audience — all

accomplished while he is not working as a family doctor in Williams, Ariz.

Landscapes

fascinate Michael Collier, as do people and planes. He has built all three interests

into a surprising career as a professional photographer, geologist and medical

doctor. His work translates landscapes, photographed from the perch of his plane,

into geological stories from around the world for a broad audience — all

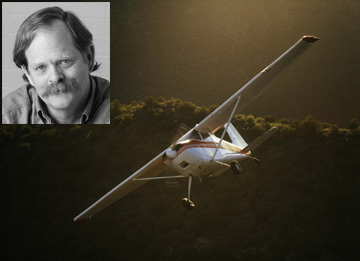

accomplished while he is not working as a family doctor in Williams, Ariz. Structural geologist Michael Collier is also a doctor, pilot and professional photographer. His work includes aerial images of the Grand Canyon and San Andreas Fault, taken from his 50-year-old Cessna 180 (shown above), and published in geology books written for the general public. Courtesy of Michael Collier; inset photo by John Running.

Collier has been a professional photographer since 1970, a vocation that has been “a thread through everything I’ve done,” he says. When he started taking photos, he most enjoyed photographing people at work. “I loved seeing how people lived their lives,” Collier says, which led him to work with a Mormon family cattle-driving for a month, to herding sheep with a Navajo family, to working with loggers.

Eventually, Collier says, “my ‘people interest’ began to inform my understanding of landscape.” He focused on how people gathered knowledge about their land and how the land shaped them — and how they in turn shaped the landscape over generations of work.

In the mid-1970s, Collier was attending Northern Arizona University and studying geology (he never studied photography formally). In 1975, under the pressure of a looming photo assignment deadline, he asked Chris Condit, a geologist friend who owned a plane, to take him up to photograph much of the Colorado Plateau. The experience and the resulting images sucked Collier into flying. “I’ve never looked back,” Collier says. “As a structural geologist, I can look down and see stories in the landscape.”

“The combination of being a superb pilot, a fantastic photographer, and a wonderful geologist who has a way with words is a lovely combination that just can’t be beat,” says Condit, who learned to kayak from Collier in return for flying, and now teaches at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. But Collier also tends to take the hard path: “Michael knew right away he wanted to be a writer and photographer,” he says, but also “wanted to get the training to qualify himself as a naturalist and geologist.” To that end, he went to Stanford University for a master’s degree under Arvid Johnson, a highly technical structural geologist.

Condit tells a story from those days, when Collier had a permit to get onto the Colorado River to double check his fieldwork before his advisor could get comments to him on his master’s thesis. Condit delivered a copy of the thesis to Collier in the Grand Canyon, dropping the text sealed in a plastic container with a parachute attached, several yards from his raft. Their adventures with friends and colleagues sound like stories Edward Abbey might have told about river-running on the Colorado and other highjinks — only happier, Condit says.

Collier “has been amazingly successful in doing things on his terms,” Condit says, a kind of stubbornness that eventually led him to medical school in the early 1980s. “He thought long and hard about it — about the best ways he could make a living that would allow him to pursue the dream of writing and photographing.”

Collier now alternates one week as a doctor with a week in the field photographing. While freelance photography pulls him “in and out of people’s lives in a hurry,” Collier says, becoming a doctor allows him to have contact with people for “the duration,” he says. “I can’t imagine not being able to walk into a room [to see a patient] and have the tools to help them.”

He also cannot imagine not going into the field. In his plane, a 1955 Cessna 180, Collier has traveled across the continental United States, and from Central America to Alaska, photographing the land below, with some of his work conducted for the U.S. Geological Survey. “I’ve spent 3,500 hours in this plane; my wife swears that when I walk up to it, the tail wags,” Collier says.

This spring he flew over Death Valley and Saline Valley, in California, and Terlingua in Big Bend, Texas, within the space of several days. His intent was to capture this year’s bumper crop of wildflowers, fed by unusually wet winter weather in the Southwest. In Death Valley, the flowers highlight the mountains’ alluvial fans.

His photo-excursions usually become books, among them A Land in Motion: California’s San Andreas Fault (1999) and Sculpted by Ice: Glaciers and the Alaskan Landscape (2004). Sometimes he collaborates with his wife, Rose Houk, a naturalist and writer who met him while working on a popular geology book about the Grand Canyon.

“I’m trying to explain processes,” Collier says. “The glacier book I just did, yeah, it’s pretty; I had a good time doing it. But most important, I want people finishing it to grasp the physics of glaciers.” While working on his 1979 book, An Introduction to Grand Canyon Geology, he was obsessed with Bowen’s reaction series, which lays out the succession of minerals that will form as silicic magma cools. “The geometry fits so nicely with the real world,” he says. “What are you going to do with something so beautiful? Hide it under the rug?”

Collier says that people always ask him what his true profession is, and he cannot answer. Although he can imagine reasons that he would be unable to practice medicine, Collier says, “I don’t think I could ever not be a photographer” — or a geologist. Seeing pictures and seeing like a geologist are “ingrained in you,” and giving up geology, Collier says, “would be like not having fingers.”

Naomi Lubick

Back to top