Geotimes

Untitled Document

News Notes

Planetary geology

A watery moon?

Early last year, images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft revealed a huge

plume of water-ice spewing from Enceladus, a tiny moon orbiting Saturn. For

more than a year, astronomers have been piecing together evidence and they are

finding that the plume stems from underground, indicating that Enceladus is

one of the few objects in the solar system known to support active volcanism.

Early last year, images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft revealed a huge

plume of water-ice spewing from Enceladus, a tiny moon orbiting Saturn. For

more than a year, astronomers have been piecing together evidence and they are

finding that the plume stems from underground, indicating that Enceladus is

one of the few objects in the solar system known to support active volcanism.

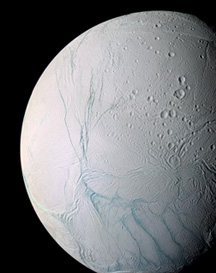

This

false-color image emphasizes cracks in Enceladus’ surface through which

a water-ice plume escapes. The younger surface of the southern hemisphere, made

evident by geologic activity and cracks, contrasts the older cratered surface

of the northern hemisphere. Image is courtesy of NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

The discovery that a moon seven times smaller than Earth’s moon could

sustain geologic activity came as a surprise to some astronomers (see Geotimes,

February 2006). Initial surprise, however, gave way to the formulation of

new models to explain the activity.

Publishing in the March 10 Science, Carolyn Porco, the Cassini imaging

team leader at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., and colleagues

describe the physical processes that they think produce the Old Faithful-like

geyser at the moon’s southern pole.

Porco first looked at the images from Cassini’s three flybys in 2005 and

thought that the plume stemmed from cracks near the moon’s southern pole.

But planetary geologists also had not ruled out that the geyser formed from

the sun warming the icy surface and producing vapors, which could then condense

into a plume in a process similar to the formation of a comet’s tail.

The new models show, however, that the most likely source of the geyser is an

underground reservoir of liquid water. They demonstrated that subsurface liquid

water erupting at the surface could explain the observed dynamics of particles

in the plume, similar to the way Yellowstone’s Old Faithful works.

“Almost undoubtedly,” some mechanism is needed “where you can

get liquid water,” says Peter Thomas, a senior research associate at the

Cornell Center for Radiophysics and Space Research in Ithaca, N.Y. Cassini measured

temperatures on Enceladus’ surface to be well below freezing, “not

warm enough to drive the plume,” Thomas says. Below the surface, however,

models suggest that warmer temperatures could sustain liquid water. Similar

to processes on Earth, that water could boil, and if a crack forms in the ice,

it could erupt as a plume of ice and gas.

Still, the model and images turn up new questions about the range of geologic

features observed on Enceladus, such as why geologic activity is currently limited

to the southern pole. The density of surface craters show that geologic activity

has been present on Enceladus for more than 4 billion years, according to Porco,

but the surfaces at the south are as young as a half a million years.

Remnants of old craters remain on most of the planet, but the southern pole

is “littered” with house-sized ice boulders, “straddled”

with 130-kilometer-long fractures and nearly free of craters, Porco and colleagues

wrote. One possibility is that a nonuniform interior — created by the moon’s

original formation, subsequent tectonics, gravitational forces or some other

process — concentrates heating at the southern pole.

To find out, Thomas says that researchers will need to more deeply analyze specific

tectonic patterns and associated stresses. But what’s currently apparent,

Thomas says, is that Enceladus’ interior is far from a “perfect onion

skin model,” and contains “all different types of geology.”

The amount of subsurface liquid water is likely small, Thomas says, but a gravity

survey of the moon could help “nail down” where water might exist

in its interior. “It’s a whole different way of hunting for water,”

Thomas says. “Apparently, there are many ways to hide liquid water.”

Kathryn Hansen

Links:

"Tiny moon, gigantic geyser,"

Geotimes, February 2006

Back to top

Untitled Document

Early last year, images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft revealed a huge

plume of water-ice spewing from Enceladus, a tiny moon orbiting Saturn. For

more than a year, astronomers have been piecing together evidence and they are

finding that the plume stems from underground, indicating that Enceladus is

one of the few objects in the solar system known to support active volcanism.

Early last year, images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft revealed a huge

plume of water-ice spewing from Enceladus, a tiny moon orbiting Saturn. For

more than a year, astronomers have been piecing together evidence and they are

finding that the plume stems from underground, indicating that Enceladus is

one of the few objects in the solar system known to support active volcanism.