Hobbit's

species status in question

Hobbit's

species status in question

Since its discovery, controversy has ensued over whether a diminutive hominid, found on the remote Indonesian island of Flores and nicknamed the "hobbit," represents a new species of ancient human. A new study this week says that the hobbit should have never been called a new species, and that it instead is most likely a modern human with a brain abnormality (see Geotimes, May 2005).

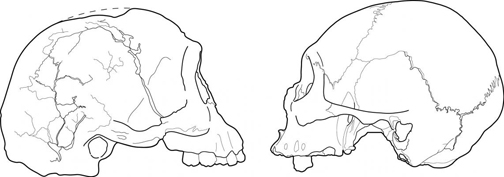

The head and brain of Homo floresiensis, an 18,000-year-old hominid found in 2004 on the Indonesian island of Flores, is considerably smaller than that of a modern, normal human. Some researchers suggest the new hominid is a dwarfed version of an early hominid, Homo erectus, while others suggest the find is actually a modern human with a brain abnormality. Photo is by Peter Brown, courtesy of Nature.

In today's issue of Science, Robert Martin, a specialist in primate evolution with the Field Museum in Chicago, and colleagues report results of a comparison between the braincase of the hobbit and the braincases of several humans with microcephaly, a disease that causes a small brain size and diminished stature. They conclude that that the hobbit is most likely a modern human with microcephaly.

The hobbit, scientifically named Homo floresiensis, was about 1 meter (3 feet) tall, 30 or so years old, female and had a brain capacity of about 400 cubic centimeters. By contrast, normal modern humans' brains are about three times that size. When the find was first announced in 2004, researchers, led by Peter Brown and Michael Morwood of the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, hypothesized that the new species was likely a dwarfed version of Homo erectus that lived 18,000 years ago and was the last known ancestor of Homo sapiens.

Islands have long been known to play tricks on the evolution of species, causing

some to grow to giants and others to shrink, due to lack of food or lack of

predators, so this seemed an "appealing" hypothesis, Martin says.

When mammals become dwarfed on islands, however, they do not scale down in brain

size to correspond with body size, Martin says. Instead, the mammals' brains

stay relatively large.

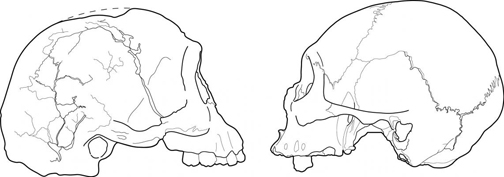

The braincase of Homo floresiensis, at left, is very similar to the braincase (at right) of a modern human with microcephaly, a disease that causes the brain and body to be stunted. Researchers examining these two specimens suggest that the Flores hominid is simply a human, not a new species of hominid. Drawing is by Jill Segard, courtesy of The Field Museum.

But in the hobbit's case, the body size is reduced alongside the brain size. For the hobbit to have been a dwarfed version of H. erectus with the appropriate brain size, its body should have been about 0.3 meters tall (1 foot) and weighed only 2 kilograms (4 pounds), smaller than an average domestic cat, Martin says. "The brain is just too small to be what [the original researchers] suggested — it falls out of the realm of anything we have ever seen before." The hobbit's brain is smaller than any other known hominid younger than 3 million years, other than one with an abnormality, or "pathology," he says.

A further complication, Martin says, is the original researchers' finding of advanced stone tools alongside H. floresiensis. A creature with a brain this size could not have produced and used such advanced tools, he says. "There is a serious conflict between the tiny brain [of H. floresiensis] and these advanced stone tools," he says.

In an almost point-by-point response to Martin's team's paper, also in today's edition of Science, Dean Falk, a paleoanthropologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee, and colleagues suggest that Martin and colleagues are off base with their criticisms of their team's original research. Falk published a comparative braincase study of H. floresiensis and a number of hominids and primates, including a modern human with microcephaly, in the March 3, 2005, Science Express, which supported the conclusion that it is likely a new hominid species, as originally reported in the Oct. 28, 2004, Nature. She and colleagues found that the hobbit's brain was unlike that of a microcephalic. The brain size of H. floresiensis falls directly within the size range for apes, especially chimpanzees and orangutans, and for early hominids who lived 3.5 million years ago in Africa, Falk says.

"Whether H. floresiensis could be another primate is an interesting question," Martin says. The brain is certainly ape-sized, but the teeth and body structure are "clearly hominid, and Homo-like," he says. Some researchers have suggested that the hobbit could be a late-surviving early hominid, "but I would rule that out," he says, "and I just don't see that this could be anything other than pathology."

Martin also disputes the finds by Falk et al., presented in the Science Express paper, that indicate that the hobbit could not have been a microcephalic. Falk and colleagues' choice of microcephalic braincase to compare to H. floresiensis was "inappropriate and unfortunate," he says, in that it was from a male juvenile, was not an original skull (it was a plaster cast), and was very different from what is usually seen in microcephalic brains. Instead, he says, the brain of H. floresiensis needs to be compared to adult microcephalics — somewhat difficult because more than three-quarters of microcephalics die before reaching adulthood.

Falk, for her part, says she's never seen anything quite like H. floresiensis, and won't rule anything out at this point, though she finds it difficult to explain away the existence of the remains of another eight individuals the same size as H. floresiensis that have been found on Flores in the same area. "I would say the chances of finding nine individuals in the same place all with the same pathology would be vanishingly slim, zero percent," Falk says.

To reach more definitive conclusions, more skulls need to be found and further

comparative studies of microcephalic and other braincases need to be completed,

Martin and Falk agree. Falk's team is currently completing such a study. For

right now, however, because only one braincase was discovered among the nine

H. floresiensis individuals, Martin posits another explanation: that

the hobbit could be a lone microcephalic living amongst a society of small people

in Flores 18,000 years ago. Closer to the equator, he says, many animals, including

humans, become smaller bodied. What is interesting to consider, he adds, is

that for the hobbit to have survived to adulthood, her society would have had

to take care of her, a characteristic that might indicate a fairly advanced

society.

Megan Sever

Links:

"Inside the hobbit's head,"

Geotimes, May 2005

"More

hobbits in Indonesia," Geotimes, December 2005

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |