|

GEOLOGIC COLUMN

The Beginning of the Trek

Lisa Rossbacher

|

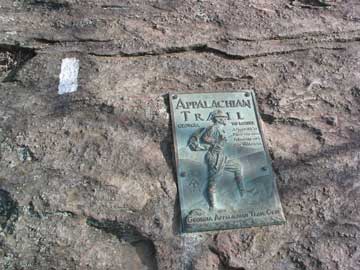

Photograph is by Lisa Rossbacher. |

I used to take the Appalachian Trail for granted.

In high school, I worked at a summer camp that was a few miles away from the trail, in Virginia's Blue Ridge Mountains. One year, at the end of the camp's sessions, about 20 of the staff hiked for a week along the trail, starting at the southern end of Shenandoah National Park and heading north. My major recollections are good music, bad food, rain, soggy everything, and a sense of accomplishment at the end of the week.

I wish I could remember what my pack weighed. Or maybe I don't.

Near where I attended college in Pennsylvania, the official mid-point of the Appalachian Trail was a few kilometers from campus. Hiking a stretch of the trail was an easy jaunt and a regular weekend activity, especially for anyone associated with the geology department. The trail was always an option.

Even in graduate school in New Jersey, I was relatively close to the trail. The intersection of it and the Delaware River, at the Delaware Water Gap, was a favorite field trip destination and day trip from Princeton.

Fast forward — ahem — 25 years. I live less than a two-hour drive from the southern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. For the last several years, visiting the trail has been looming ever larger on the to-do list. Finally, I set out to see this landmark.

The starting — or ending — point for the trail is at Springer Mountain in Georgia. Unlike my earlier experiences with the trail, this is not a place to park the car, put on a knapsack, and take a day hike. Just getting to the starting point is an expedition, with a nearly 13-kilometer-long (8 miles) hike along an approach trail, described by signs as "strenuous." Indeed, the trail is mostly uphill, along a rocky, rooty, and, in our case, icy path.

I can only begin to imagine how it would feel, after months or years of planning, to confront this approach trail as the last obstacle before actually reaching Springer Mountain and the trail. The official trail terminus is a knob of schist, with a plaque and a drawer cut into a rock ledge to protect the log book for hiker registration, which is full of short, hopeful messages. Bill Bryson described well the feelings of anticipation and trepidation in A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail.

Full disclosure: A civilized option is available to visit Springer Mountain without having to spend a night at the shelter or hike the 25-kilometer roundtrip in a day. The Len Foote Hike Inn is an eco-lodge that is located close to the summit of Springer Mountain; guests can get family-style meals and a bunk in an environmentally friendly facility. From the Hike Inn, Springer Mountain is just 8 kilometers away — a tough day hike, but not a debilitating one.

Access to the southern end of the trail used to be easier. Before 1958, the terminus was at Mount Oglethorpe, about 22 kilometers northeast of Springer Mountain. Mount Oglethorpe had issues: Because the summit could be reached by road, considerable vandalism resulted, including damage to the marble monument honoring the mountain's namesake, Georgia's founder James Oglethorpe. In a sense, the approach trail should be difficult, making the actual official location harder to reach and perhaps winnowing out the unprepared.

On the 8-kilometer trek from the Hike Inn back to our cars, we met a couple headed toward Springer Mountain. They appeared to have more gear than required for a few nights on the trail, but not as much as a serious through-hiker going the entire 3,494 kilometers (2,174 miles) would likely carry. One of our group asked conversationally, "Where are you headed?" The woman snapped back, "Maine," and we all mentally extended our sympathies to her companion, who shrugged as he trudged after her.

For obvious meteorological reasons, most people who plan to hike the entire trail in a single season start in Georgia and head north, rather than try to hike SOBO, or southbound. Data are sketchy about the number of hikers who are NOBO, (northbound), from Springer each year, but the Appalachian Trail Conservancy estimated that about 1,150 hikers started at Springer Mountain in 2006, and 309 had arrived at Mount Katahdin, Maine, as of Feb. 1, 2007. Since 1936, more than 9,000 people have completed the Appalachian Trail, some of them over multiple years. Overall, the single-season completion rate is about 25 percent NOBO, slightly lower SOBO.

And I felt good — really good — about just getting to the starting point at the southern end of the trail. On a roundtrip hike of almost 18 kilometers, I walked only about a kilometer of the actual Appalachian Trail. Even that wasn't easy, but I knew I'd have a hot meal and a bed that night.

The experience was a reminder of what's important in the field: the basic elements of survival, of food and shelter, of planning and preparation. It's also a reminder of why many of us care about being outdoors and the insights it brings. We get new perspectives on the world around us, literally and figuratively. Isn't this why we became geologists in the first place?

I’ll never take the Appalachian Trail for granted again.

Subscribe

Subscribe