|

EDUCATION & OUTREACH

Feeling the cosmos

Cassandra Willyard

NASA, ESA, and M. Estacion (STScI) |

| Blind and low vision students evaluated Touch the Invisible Sky during the National Federation for the Blind's Youth Slam in Baltimore this summer. |

Steven Booth is a technology specialist at the National Federation for the Blind in Baltimore, Md. As part of his job, he tests products designed to help people who are blind or visually impaired engage with the world around them. It’s a job that wouldn’t have existed when he was young. Back then, many people thought fields like engineering, science and technology were out of reach for the blind. “We were all told we couldn’t do it,” he says.

Today NASA is trying to send the opposite message. Over the past six years, the agency has released three books on space that students of any visual ability can use. These books combine text and Braille with dozens of color and tactile images that students can see with their eyes and feel with their fingertips. For blind students, the books have been a godsend. “Being able to apply their own minds to the analysis of a picture stretches their imagination and gets them to think in new ways,” says Mark Riccobono of the National Federation of the Blind.

The mastermind behind these books is Noreen Grice. She became involved in making science accessible to the blind in 1984, while working as a part-time ticket-taker at the planetarium at the Boston Museum of Science. One day a group of kids from Perkins School for the Blind (Helen Keller’s alma mater) paid a visit. When they left, Grice asked them whether they had enjoyed it. “They thought the whole situation stunk,” Grice says. “That left me bewildered because I thought the planetarium was a very exciting place.”

Grice, then a student at Boston University, decided to write an astronomy book for the blind as her senior project. She knew she would need pictures to make it accessible, but she didn’t know how to make them. So she asked around. “And in 1984, the answer was you glue string to cardboard,” Grice says. So she temporarily abandoned the idea of pictures and completed the text. Two years later, Grice — who says she doesn’t like unfinished projects — found a way to make astronomical diagrams using a machine that can convert computer images into raised dots. She combined the drawings with text from her senior project and, with funding from the Boston museum, published her first book: Touch the Stars. The first 400 copies sold out in a year.

Ozone Publishing |

In 1999, Bernhard Beck-Winchatz, an astronomer at DePaul University in Chicago, Ill., stumbled across the book in a museum gift shop. “I got an e-mail,” Grice says. “He said, ‘It’s a shame there isn’t something like this for Hubble.’” With a $10,000 educational outreach grant from NASA, the pair put together Touch the Universe: A NASA Braille Book of Astronomy. Aimed at junior high students, the 2002 book contains images of planets, nebulae, stars and galaxies from the Hubble Space Telescope. It was a learning experience for Grice. First, she had to decide which parts of the images to give texture. “That’s the big challenge because it’s very subjective,” she says. Luckily Grice has an astronomy background, so she can identify which parts should be emphasized.

Instead of using raised dots as she did in Touch the Stars, Grice spent her evenings painstakingly carving the texture into thin plastic sheets at her kitchen table. She used patterns to represent different colors and features. Raised lines, for example, denoted blue. Dotted lines signified rings. “The most difficult thing to represent is diffuse gas,” she says. The prototypes went to the Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind in Colorado Springs to be evaluated by students. Some of her images were successful. Some weren’t. “You can’t raise everything,” Grice notes: One image called Hubble Deep Field North, a collection of hundreds of tiny galaxies, just didn’t work. “The kids said, ‘We’re lost. This picture is too much,’” she says.

After revising the images based on the students’ suggestions, Grice sculpted the final versions on metal plates, which were then placed in a heat vacuum machine to create molded plastic pages. These transparent pages served as a tactile overlay to the Hubble images. Grice planned to make a few hundred copies like this, putting plastic sheets in the heat vacuum one at a time. In fact, she thought it would take her all summer. But after a press conference at the 2001 American Astronomical Society convention, hundreds of orders poured in. So Joseph Henry Press stepped in to help Grice transform the overlays into embossed color pages that could be mass produced.

Ozone Publishing |

| In this Hubble image of the Crab Nebula from Touch the Invisible Sky, dots and squiggles give the image texture. |

Her next collaboration with NASA, Touch the Sun, came out three years later. Joe Gurman, a scientist at NASA’s Solar Data Analysis Center in Greenbelt, Md., enlisted Grice to work with him on the project after seeing a copy of Touch the Universe. “In those days, we were all pretty awed by the images that SOHO [the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory] was putting out,” he says. “It seemed unfair that our blind fellow taxpayers weren’t able to enjoy the same awe and mystery.”

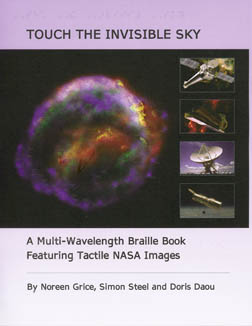

Grice’s third NASA book, Touch the Invisible Sky, was unveiled in January 2008 at the National Federation for the Blind. The book, aimed at high school students, introduces the electromagnetic spectrum and explains the importance of multi-wavelength astronomy. The texture in Grice’s latest book comes from acrylic squiggles, dots and lines embossed directly on the page. Only when you pull together information from the whole spectrum do you get a clear, rich picture of objects such as black holes and supernovas, says Simon Steel, an astrophysicist at NASA and one of Grice’s co-authors.

Touch the Invisible Sky is especially important because it showcases things that aren’t visible to anyone, Riccobono says. “This book fills a huge need,” he says. “There are things out there beyond the naked eye that everyone can work on.” Information that comes from the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Spitzer Space Telescope, for instance, is numerical. That information is translated into pictures for the sighted, but you don’t need eyes to analyze the data. “It’s just ones and zeros,” Gurman says. “Who’s to say that a person with a visual impairment isn’t the best person to do this science?”

Booth thinks NASA’s latest effort is “quite a piece of work.” Books that the sighted and the blind can both use will only help encourage accessibility in other areas, he says. “We’re gradually breaking down barriers.”

Subscribe

Subscribe