While

Gulf State residents and policy-makers assessed the damage after hurricanes

Katrina and Rita, Congress pledged billions of dollars to restore New Orleans

and other affected communities’ infrastructure. Part of that funding will

go toward restoring some of the natural infrastructure as well: the wetlands

that once covered Louisiana’s Mississippi Delta.

While

Gulf State residents and policy-makers assessed the damage after hurricanes

Katrina and Rita, Congress pledged billions of dollars to restore New Orleans

and other affected communities’ infrastructure. Part of that funding will

go toward restoring some of the natural infrastructure as well: the wetlands

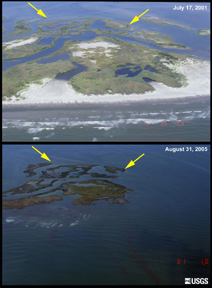

that once covered Louisiana’s Mississippi Delta.The Chandeleur Islands — shown here in July 2001 (top) and on Aug. 31 (bottom), two days after Hurricane Katrina — changed dramatically with the passing storm surge and large waves, which submerged and washed away large sections of sand and marshes. Image courtesy of USGS.

Even before the past season’s devastating hurricanes, Louisiana’s wetlands were in rough shape. More than a century of building dams, levees and canals to control the Mississippi River changed the wetlands, limiting sediment and leading to soil compaction from the loss of vegetation. Background rates of subsidence up to several millimeters a year led to more loss of land. Some estimates for the past 50 years put the rate of wetland loss at more than 60 square kilometers (about the size of Manhattan) a year.

“Deterioration of the Mississippi Delta involved a complex set of factors,” says John Day, a professor at Louisiana State University’s Coastal Ecology Institute in Baton Rouge. In addition to “the extreme internal disruption of the delta” from earlier U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ activities, he says, researchers have found that “oil and gas extraction led to enhanced subsidence” (see Geotimes, August 2005). Day, who is also a member of the National Technical Review Committee advising the Army Corps on how to proceed with a basin-wide restoration project, says that any restoration efforts will have to deal with these issues, as well as with impending land loss from rising sea level, expected to occur with changing climate.

“Only in the last 75 years [has] New Orleans moved in a massive way into the wetlands, so that you have a city below sea level,” Day says. “Wetlands will help protect the city.” Healthy wetlands absorb the impact of storms, dissipating their energy as they hit vegetation and rough surfaces.

The decline of Louisiana’s wetlands, however, was not responsible for the devastation Hurricane Katrina wrought on New Orleans. Instead, the blame lies with the storm’s unexpected turn past Lake Pontchartrain, a “huge” lake separated by manmade walls from the city, but with “no marsh system in that area to protect from water surges,” says Curtis Richardson, director of the Duke University Wetland Center. Still, he says, wetlands “would have helped” cushion some of the blow.

The general argument for restoring wetlands focuses on ecosystem health — for protecting shrimp fisheries (which netted $135 million in Louisiana in 2003), as well as flyover territory for migrating birds and local animals’ habitats. Most recently, a report called Coast 2050, written by local scientists, policy-makers and the Army Corps, proposed a variety of ways to reclaim Mississippi sediments for the wetlands and for rebuilding protective coastal barrier islands. A related experiment showed that controlled breaches for freshwater flooding from the Mississippi River could help sustain sinking marshes that saltwater is slowly encroaching upon. Another project proposed by the Army Corps would use dredging materials from canals to build up wetlands.

“Back-of-the-envelope calculations” made in 1999 produced a ballpark figure of $14 to $15 billion to achieve the Coast 2050 goals, says Denise Reed, a geomorphologist at the University of New Orleans. But, “nobody knows how much” such projects will cost exactly, she says.

Some critics have questioned how much marsh restoration efforts could help in Louisiana. “I’m not sure this very vulnerable, rapidly subsiding area is the best place to try massive environmental restoration,” particularly with such a large price tag to be paid by taxpayers, says Robert Young of Western Carolina University, who wrote a Sept. 27 editorial in The New York Times with David Bush of the University of West Georgia. “If we are going to restore wetlands, there are many other places,” Bush says, where it “would cost a fraction of the money.” They also point out that hurricanes Katrina and Rita ran roughshod over barrier islands off the coast of Mississippi, another region that regional scientists would like to restore.

“The devil is in the details here,” Reed says. Although many barrier islands far offshore were decimated, barrier islands closer inland did provide protection.

Various stakeholders in the region argue that human-made and natural infrastructures must work together in any future restoration plan. “That’s what our goal is to do,” Reed says: Build naturally sustainable marshlands to protect population centers, but not as their sole protection.

For now, the Army Corps plans to return New Orleans’ levees to their pre-storm strength — able to withstand a Category-3 hurricane — before the next hurricane season. Only then does the Corps plan to consider other options, such as an ocean-gate system first proposed in the 1960s, like the one protecting Holland. At the same time, some local leaders are hoping to get Category-5 protection in less than six months, but funding remains contentious.