|

News Notes

Geochemistry

Canada's diamonds face old age

During the last few decades, prospectors and exploration companies have succeeded in locating diamonds in the extreme environment of Canada’s Arctic, and the country has since seen a diamond rush as mining companies have moved in to stake their claims (see Geotimes, April 2006). As geologists get in on the rush, they are uncovering the unique origins of Canadian diamonds, and finding not only that they are surprisingly old, but also that they have implications for the timing of Earth’s early tectonic processes.

During the last few decades, prospectors and exploration companies have succeeded in locating diamonds in the extreme environment of Canada’s Arctic, and the country has since seen a diamond rush as mining companies have moved in to stake their claims (see Geotimes, April 2006). As geologists get in on the rush, they are uncovering the unique origins of Canadian diamonds, and finding not only that they are surprisingly old, but also that they have implications for the timing of Earth’s early tectonic processes.

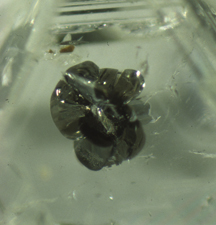

A sulfide inclusion is visible inside a diamond from the Jwaneg Mine in Botswana. Similar inclusions found within Canadian diamonds helped researchers date the diamonds to be among the oldest on Earth. Photograph is courtesy of J.W. Harris.

Scientists have long known that diamonds are old, says Steve Shirey, a geochemist at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism in Washington, D.C. Diamonds from Africa and Siberia, for example, have been dated at about 3 billion years old, he says. But now, Shirey and Kalle Westerlund, a visiting graduate student from the University of Cape Town in South Africa, and their colleagues have used a precise dating method to reveal that some Canadian diamonds actually formed about 500 million years earlier.

Before the team could date Canada’s diamonds, they had to wait for mining companies to move in with elaborate rigs to pull the diamond-bearing rocks from the ground. Ekati Mine in the Northwest Territories, the first operational diamond mine in Canada, supplied the team with samples. They then measured the isotopes rhenium and osmium, and knowing the rhenium decays to osmium, the team calculated that the diamonds formed 3.52 billion years ago.

To find out if they could learn more about the rocks than just their age, the team next looked at iron sulfide inclusions inside the diamonds that contain a mineral record of how the diamond formed. “Like anything in geology, you look for what is special, and might tell you something new,” Shirey says.

Mineralogists have shown that diamonds form from similar elements, including carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and sulfur, but the origin of that material is not always the same. Diamonds have previously been grouped into two categories: “peridotitic” diamonds, which formed from material hundreds of kilometers below Earth’s surface, and “eclogitic” diamonds, which formed from materials in Earth’s crust that were recycled into the planet via plate tectonics. Scientists can tell a diamond’s origin by looking at its composition and the chemistry of its inclusions.

Surprisingly, the team found that while inclusion composition clearly indicated that the diamonds formed deep in Earth as peridotitic diamonds, osmium isotopes indicated involvement from surface-recycled materials, similar to eclogitic diamonds. That surface recycling contributed to the diamonds’ formation 3.52 billion years ago implies that some sort of subduction process likely existed at that time, the researchers reported in the September Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology.

According to Thomas Stachel, a geologist with the diamond research lab at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, the old age is significant in that it suggests that the formation of diamonds does not require Earth’s early continents to have been stable, as some scientists previously thought. That stabilization did not occur until about 2.5 billion years ago, but this study shows that diamonds started growing 1 billion years before that, he says. “It’s a great piece of work.”

The next step, Shirey says, is to analyze Canadian diamonds from the Diavik mine, also in the Northwest Territories. That information will help determine if the Ekati Mine’s diamonds are truly anomalous in their age.

Kathryn Hansen

Links:

"Diamonds Bedazzle Canadian North," Geotimes, April 2006

Subscribe

Subscribe