|

News Notes

Mineralogy

Mineral clock not set in stone

Dating a hydrothermal deposit — a vein containing ore minerals left behind by hot, mineral-rich fluids percolating through rocks — is a notoriously thorny problem, but a radioactive mineral may now offer a solution. Once used to date the rocks that hosted the ores, the mineral may be more useful in pinpointing the age of the ores themselves, according to a new study.

|

| Geologists study the Birch Creek pluton, a mass of granite that intruded into 500-million-year-old sedimentary rocks 80 million years ago. Photograph is by John C. Ayers. |

|

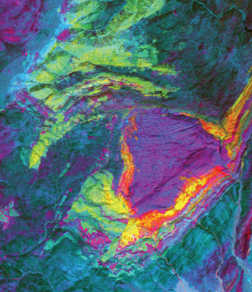

| This satellite image (colored to show the different types of rock) shows a different view of the pluton. Mineral crystals in the older rock, dissolved and recrystallized by hot hydrothermal fluids, can help pinpoint the intrusion’s age. Image is courtesy of Patrick Kozak. |

Fueled by heat from intruding magma into a mountain or rising at a plate boundary, water circulating through a rock’s pore spaces and fractures can interact with, dissolve and transport minerals. Whenever the water’s chemistry, temperature or pressure changes during its travels, it may deposit some of the minerals it has carried, filling fractures and other spaces in the rock.

Determining when these hydrothermal deposits formed is no easy task, says Joseph Pyle, a metamorphic petrologist at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y. “When you’re trying to date hydrothermal deposits, there’s no real evidence that the date that you’re getting is related to the fluid infiltration,” he says. “To actually explicitly state that [a] mineral formed in response to a particular pulse of fluid has been, up until now, a well-nigh impossible thing to do.”

Now, John Ayers, a geologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues say that a mineral called monazite may offer one solution to this dilemma. Monazite crystals contain the radioactive element thorium, which decays over time into lead. By measuring the ratio of thorium to lead isotopes, scientists can date a monazite crystal’s age.

In the past, researchers thought that this method could be used to date the formation of the ore deposits’ host rock, as they thought monazite was impervious to dissolution by the hydrothermal fluids. Instead, Ayers says, monazite dissolves readily in some hydrothermal fluids, thus “resetting” the rock’s radioactive clock to the time when it was altered by the fluids’ activity. That means the monazite can identify and date the fluid intrusions themselves, Ayers and colleagues wrote in the August Geology.

The test of monazite’s dating capabilities came from measuring oxygen isotopes in monazite crystals from the Birch Creek Pluton in eastern California, a granite formation that intruded about 80 million years ago into the 500-million-year-old Deep Springs Formation. Monazite crystals in the host rock that have recrystallized in the hydrothermal fluids will take on the fluids’ oxygen isotope composition, distinguishing them from unaltered crystals in the original host rock.

In the Deep Springs Formation, the team analyzed monazite crystals ranging up to 700 meters from the edge of the granite intrusion. Close to the contact between host rock and granite, the oxygen ratios in the monazite did change and approached the values found in the granite — indicating that the crystals must have dissolved and then precipitated from the hydrothermal fluid, Ayers says.

The team’s find, which shows that it is possible to map these deposits in both space and time, “is pretty powerful,” Pyle says. “To be able to combine both spatial and temporal fluid flow information, and chronology — it comes close to approaching a holy grail for metamorphic petrology,” he says. “If you could just throw pressure information in there, you could go home and drink a beer.”

Although the new research suggests that monazite may not be a valuable tool in dating the host rocks, measurements of uranium-bearing zircon crystals suggest that geochronologists can continue to use zircon’s isotopic ratios to tell the time of the original rock’s formation. The study also has implications beyond dating hydrothermal ore deposits, Pyle says.

Because monazite can contain large concentrations of radioactive elements, scientists have considered synthetic monazite as a possible container to store radioactive waste underground, but they will now have to be careful about the potential that the radioactive mineral could interact with the groundwater, he says.

Another possible use for monazite, Ayers says, may be that the dating could help identify how fluids move along seismic faults. After a large earthquake, fluids can flow along the earthquake fault, dissolving and recrystallizing the monazite, which can then tell researchers when an earthquake last occurred.

Carolyn Gramling

Subscribe

Subscribe