|

Feature

Alaskan Villages Weigh In On Mining Debate

Kathryn Hansen

In mid-September, elders from Nondalton, a native village in southwestern Alaska located at the edge of Six Mile Lake, took to the air. From the sky, the elders looked down at their village and the larger Bristol Bay region, noting changes from years past. The caribou were nowhere near their usual grounds, according to Jack Hobson, president of the Nondalton Village Council.

In mid-September, elders from Nondalton, a native village in southwestern Alaska located at the edge of Six Mile Lake, took to the air. From the sky, the elders looked down at their village and the larger Bristol Bay region, noting changes from years past. The caribou were nowhere near their usual grounds, according to Jack Hobson, president of the Nondalton Village Council.

Workers operate a drill rig at the eastern side of the controversial Pebble Mine deposit in Alaska. The site’s vast quantity of gold and copper make the site economically alluring for developers, but some natives worry that a mining operation will adversely affect the region’s fish. Photograph is by Erin McKittrick.

For generations, natives of Nondalton have relied on the caribou, as well as moose, fish and other renewable resources, to maintain the subsistence lifestyle that currently drives the majority of the village’s economy. Now, however, natives living in the village have voiced concern about those resources as a new type of development begins to take hold in the region. “Ever since the mining operation moved in with loud helicopters, all the caribou moved toward the northwest,” Hobson says.

In 1988, explorers for Cominco (today called Teck Cominco) first discovered minerals below the ground, and more than a decade of further exploration found that the site appeared to hold the largest “contained” gold and copper deposit in North America. The large-scale operations needed to mine the minerals, however, are also producing large-scale controversy among Alaska Natives, mining companies, environmental groups and government officials.

Still, other large-scale mining projects have taken hold across Alaska that have helped Alaska natives to develop the economies of impoverished villages, while maintaining their traditional subsistence lifestyle. Whether a mine is controversial or beneficial, however, such large-scale operations pose significant changes to the land and the people who live there.

Whose land is it anyway?

In 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. At the time, some government officials thought that $7.2 million was too high of a price to pay for land that many considered to be a remote region without economic promise, calling the purchase Seward’s Folly after Secretary of State William Seward, who favored the deal. The $7.2 million price tag would end up paling in comparison, however, to the revenue from oil deposits discovered at Prudhoe Bay just over a century later in 1968.

By the time oil was discovered, Alaska had only been officially a state for a decade, and land ownership issues had not yet been ironed out. The land ownership debate escalated when oil companies wanted to build a pipeline on land over which native populations claimed ownership.

The debate gave rise to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), which Congress passed in 1971. The act was designed to resolve land claim issues. Unlike the decision in the lower 48 states to set aside land to be managed by Native American tribes, ANCSA invoked a corporate-model-style settlement: Twelve Native-owned “regional corporations” were established, and each selected lands for which they would own both the surface and subsurface rights.

About 10 percent of the state’s land is now owned by the 12 for-profit Native Regional Corporations. NANA Regional Corporation, for example, which has rights to more than 98,000 square kilometers of land in northwestern Alaska, brings in profit through business ventures such as mining, engineering and government contracting.

The regional corporations in turn oversee more than 200 “village corporations,” within their land selections. Alaskan natives alive when the act was passed were entitled to 100 shares each in their particular regional corporation.

A developing economy

Much of the land originally selected by NANA Regional Corporation under the 1971 land settlement was based on its ability to provide the fish and wildlife resources to maintain a subsistence-type of lifestyle, says Fred Smith, a member of NANA Regional Corporation’s board of directors. Subsistence relies on hunting, fishing and gathering vegetation to obtain enough for a village to “sustain” itself, which differs from the cash economy of most of the rest of the United States. Subsistence alone, however, does not pay for houses, electricity, TV and the Internet, Smith says.

Thus, a decade after Congress passed ANCSA, Alaska’s economy remained like that of a third world country, Smith says. “We didn’t have a lot,” he says. They did have commercial fisheries and publicly funded establishments, such as schools, post offices and government offices, which didn’t contribute much to the state’s economy, he says.

By the mid-1980s, however, metal prices began to skyrocket, and NANA began looking toward mining the mineral deposits that exploration efforts have turned up, as a means to develop the economy. By 1989, Red Dog Mine opened, becoming the word’s largest zinc mine and the first large-scale mining operation on Alaska Native land. The mine as it currently exists could continue to produce zinc for 50 years, which means continued employment opportunities, according to NANA, of which 62 percent are Alaskan native shareholders.

But in 2002 and 2003, zinc prices fell to historic lows, sinking to prices half of what NANA expected when constructing Red Dog Mine in cooperation with Teck Cominco. The mine operated at a loss those years, which means that native corporations all over Alaska, with whom NANA Corporation shares 70 percent of its profits, also suffered.

But in 2002 and 2003, zinc prices fell to historic lows, sinking to prices half of what NANA expected when constructing Red Dog Mine in cooperation with Teck Cominco. The mine operated at a loss those years, which means that native corporations all over Alaska, with whom NANA Corporation shares 70 percent of its profits, also suffered.

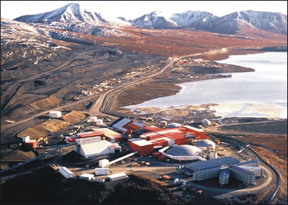

Red Dog Mine, the world’s largest zinc mine, is located on land owned by NANA, an Alaska native regional corporation that owns surface and subsurface rights to 2.3 million acres in northwestern Alaska. Photo is courtesy of Fred Smith.

In the last few years, however, mineral prices have again been on the rise. That’s the “number one reason” that Alaska is seeing a renewed interest in mineral exploration and development, says Jason Metrokin, a member of the Bristol Bay Native Corporation’s board of directors. The second reason for a renewed interest in exploration is that technology has advanced, making it easier to find deposits, as well as to determine the depth and concentration of the minerals, he says.

One region of current interest spans an area of 225 square kilometers on state-owned land in the Bristol Bay region of southwestern Alaska. Although the amount of recoverable minerals is yet to be determined, early estimates suggested that the deposit could hold as much as 26.5 million ounces of gold and 16.5 billion pounds of copper, according to Northern Dynasty Mines Inc., a mine development company based in Anchorage, Alaska, which in turn is owned by Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd., based in Vancouver, Canada.

At the site, development of an open-pit mine called the Pebble Project is now in the project design stage. Northern Dynasty has not yet finalized plans, nor have they applied for the requisite slew of environmental and state permits. The mine, while logistically easier to build than other mines in Alaska, such as Red Dog Mine, faces a tough permitting process, Smith says.

Before the mine can be developed, an Environmental Impact Statement is required, says Patty McGrath of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in Seattle, Wash. Traditionally, if a mine will be on federal land, the federal agency that oversees the project is responsible for producing the statement. The Pebble Project, however, exists on state land, so either the EPA or the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers will draft the document, which will take into account scientific data to determine the scale of the mine’s potential impact on water resources, wetlands, wildlife and fish, McGrath says.

Although the data is not yet in, strong opinions, both for and against the mine, have already been voiced, Metrokin says. The Pebble Project deposit is located north of Lake Iliamna, Alaska’s largest lake, and in the vicinity of three Bristol Bay villages: Iliamna, Newhalen and Nondalton. And residents of Nondalton are worried about potential impacts of the mine, and how it will affect the area’s caribou herds and fish.

Pebble Controversy

The proposed area for the Pebble Project mine is a “very important watershed for tribes and the state,” especially regarding the lake’s fish resources, McGrath says. Metrokin says that he doubts there is any one individual in Bristol Bay that is not affected by fisheries: The industry is “that big,” he says.

Nondalton’s Hobson says that the mine’s location, at the head of a major river and numerous feeder streams, would likely impact the fish. “There’s no way they could convince us that they will be able to keep [mine waste] out of the water,” he says.

Controversy over the location of the mine has heated up, gaining the attention of U.S. Sen. Ted Stevens (R-Alaska). Stevens, who has been an outspoken proponent of drilling for oil and gas in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, officially stated that he opposed the project in the Bristol Bay region over concern “that development will further harm the salmon stocks there,” according to a spokesperson for Stevens.

Added to the issue of location is the issue of scale. The Pebble Project deposit is very large compared to anything else in Alaska, McGrath says. Indeed, mining has been “an industry that we’ve seen come and go in Bristol Bay, but not to the extent that folks are talking about in terms of Pebble Mine,” Metrokin says. “That’s a much different animal.”

The mine also poses social concerns, Metrokin says. Out of the 30 villages in the Bristol Bay region, only two have populations of 1,000 or more. The influx of 1,000 or more workers during construction of a Pebble Project mine could make it the third largest community in that region, he says. “How do you support a large influx of people and all of the issues, positive and negative, that that brings to a community?” he asks.

Still, Metrokin says that Bristol Bay Native Corporation holds a neutral position on the Pebble Project, as it “needs to be further defined.” As the project now stands, it “changes constantly, and newfound scientific information is still yet to be put on the table,” he says.

Project information, including data that backs the project design and its safety, as well as empirical data to show that the environment will be protected, is currently being collected, says Bruce Jenkins, CEO of Northern Dynasty. “In the full light of day, the senator and other stakeholders will have all of that information and then can form final opinions,” he says.

And Jenkins is confident that the more than $110 million in research and planning that Northern Dynasty will have invested by the end of 2006 will prove worthwhile. The Pebble Project deposit has been and will be a “major economic boon,” Jenkins says, for what he calls a “very impoverished region” with high unemployment.

Already, Northern Dynasty has hired more than 100 people from more than 25 different communities, contributing more than $3 million last year to those communities, he says. And in the future, the mine will support more than 1,000 local hires, lasting the span of the mine’s lifetime.

Each mine a different story

While the Pebble Project controversy has stolen the limelight, native corporations are pursuing other lesser-known resource development projects on their own land. NANA, for example, will be looking to develop copper deposits, and also plans to look into the potential for oil and gas, according to Walter Sampson of NANA’s land and resources department. Large companies, including Shell, also are looking to the region to develop offshore oil and gas, Sampson says.

In the end, Smith says, Alaska Natives need to develop resources to fuel their economy, but some obstacles stand in the way, including popular perceptions. The American public views Alaska as “the American park and the last frontier,” he says. “Alaska’s big and we have a lot of beautiful country and a lot of wildlife, but what are Alaskans to do without being able to develop resources that fuel our own economy?”

Still, Smith says that he does not stand behind all mining developments. “Every mine needs to be looked at in its own right because every mine is different,” he says. Each site has a different geologic makeup that poses different environmental concerns, he says. “I think you need to take a close look at whether or not [a site] could be mined without doing a lot of damage to the environment and to the resources.”

Nondalton village’s Hobson agrees, and after having toured about five mines in Nevada, he says that he can see positive value in mineral development. But geographical location is “really critical,” he says. “Where they’re trying to put [Pebble Mine] is in the heart of our subsistence-use area, and not only for this village — there are 12 villages around that area that would be directly affected by whatever goes on up there,” he says.

Exactly what those effects are remains to be seen. For better or for worse, however, the onset of large-scale mineral development is spurring change for Alaska Natives. “Change is just something that we’re trying to adjust to and live with day to day,” Hobson says.

Hansen is a staff writer for Geotimes.

Subscribe

Subscribe