by Michael Novacek. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2002), ISBN 0-374-27880-6, Hardcover, $26.

Louis L. Jacobs

Check out this month's On the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The popular Geomedia feature now available by topic.

Book Review:

Time Traveler: In Search

of Dinosaurs and Ancient Mammals from Montana to Mongolia

Maps:

Aggregates

map helps save Quecreek miners

|

Time Traveler:

In Search of Dinosaurs and Ancient Mammals from Montana to Mongolia by Michael Novacek. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2002), ISBN 0-374-27880-6, Hardcover, $26. Louis L. Jacobs |

Michael Novacek, a distinguished paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural

History, is probably best known to the public for his work on the spectacular

fossils of Mongolia. These fossils were the subject of his first book, Dinosaurs

of the Flaming Cliffs. Time Traveler is his second book, and his

acknowledgements make it clear that he wrote it because he and his readers enjoyed

the passages in his first book about his learning to be a paleontologist, his

feelings and experiences.

In Time Traveler, Novacek expands on these themes and delves into his

fieldwork prior to Mongolia. He states that the book is not “a book about

a life, but largely about a life in the field.” In that sense, it is an

autobiography, albeit an unconventional one. His “recollections are meant

to show how a childhood of dinosaur dreams was transformed into a paleontological

career.” The book is just what Novacek promises. Time Traveler is

a primer for a successful career in paleontology.

Together, the book’s many themes give it many layers and serve a broad

audience. Consequently, as one might imagine, depending on the experiences and

expertise of the reader, not all parts of the book are equally informative or

entertaining. Thus it is a good but somewhat hummocky read, speeding up and

slowing down like a field vehicle crossing the badlands.

The first three chapters describe Novacek’s childhood in Los Angeles, his

desert explorations, and his affection for the Santa Monica Mountains. He describes

a trip to the Grand Canyon with his family to introduce principles of stratigraphy

and time. He discovered his first impressive fossil, a trilobite, in Wisconsin,

where his family moved for a short interval before returning to southern California.

He enters a rock-band musical phase, which segues into his undergraduate years

at UCLA.

In his narrative, Novacek is kind to his paleontology professors. They obviously

recognized in him the talent that has since blossomed, and he responded to their

consideration. His paleontological fieldwork began with Peter Vaughn of UCLA

in Paleozoic rocks of the Colorado Plateau and southern New Mexico, a spectacular

but difficult field area that yields its treasures begrudgingly, as described

in six chapters. Novacek uses these chapters to provide further background in

geology and paleontological methods.

This section also hosts a few errors: In a discussion about coprolites, he explains

the process of CAT-scanning, which he incorrectly calls “cathode axial

tomography” (instead of computed axial tomography) and which he says uses

“lasers to make an internal image map” (instead of X-rays). These

are only errors; I was hurt to read Seymouria unkindly referred to as a “sluglike

labyrinthont amphibian.” How could this glamorous amphibian misfit with

brawny terrestrial limbs be likened to an askeletal mollusk? But this is just

a paleontologist’s infatuation with the extinct.

In the early 1970s, after a stint as a crew chief in the La Brea Tar Pits, Novacek

set off for San Diego, continuing his fieldwork in the wilds of urban paleontology.

At San Diego State University he studied under Jay Lillegraven (now at the University

of Wyoming). Under Lillegraven’s tutelage, Novacek completed a thesis on

the insectivoran mammals from late Eocene sediments in San Diego and its environs.

With his thesis, Novacek began to define his place in the profession. He pursued

his doctoral studies under Don Savage and Bill Clemens at the University of

California, Berkeley. Through them he participated in fieldwork in the classic

badlands of the Bighorn and Washakie basins in Wyoming, and Crazy Mountain Field

and the Hell Creek Formation in Montana. These chapters afford the opportunity

to discuss the colorful history of paleontology in western North America.

After completing his doctorate, Novacek took a position at his alma mater in

San Diego, Lillegraven having moved to Wyoming. But Novacek was not in San Diego

long before he migrated permanently to the American Museum of Natural History

in New York.

His time in San Diego led him to fieldwork in Baja California, the first field

project that was truly under his direction. The locality was known from earlier

work and the fossils were said to be Paleocene. Novacek’s team found more

fossils, including the placental Hyopsodus, which a missing comma on

p. 169 transforms into an opossum-like marsupial; and Meniscotherium,

which for the same reason became a rodent. But those who know the names will

know the taxa and the editing will not matter. The new fossils Novacek and his

team found there indicated an Eocene age. They utilized the systematics of fossil

vertebrates, marine and nonmarine stratigraphy, and magnetostratigraphy to dispel

the notion of asynchrony of early Eocene mammalian faunas of North America,

a conclusion that would have relevance in later years as the global climate

controversy heated up.

Following Baja, Novacek tackled Chile, to which five chapters are devoted. He

took a nasty spill from a horse, the last of a number of calamities chronicled

in the book, but continued in his fieldwork. The description of the discovery

of the Tinguiririca fauna is my favorite part of the book because it was real

discovery from the beginning. No one had ever found bones there before, and

the find was in rocks that represented an interval of geologic time not previously

known in South America.

From South America, Novacek’s search led to Yemen in the southern portion

of the Arabian Peninsula. Pickings were slim, but the country is fascinating

and he describes its mountains and deserts well. One legendary home of the Queen

of Sheba is Marib on the sandy edge of the Empty Quarter of Arabia, Novacek’s

last stop in the country.

From the sands of Arabia, Novacek traveled to the sands of Mongolia, the subject

of his first book. Here he provides more background into how he got there and

presents some interesting results. The magnificent and numerous skeletons, including

dinosaurs brooding on nests, were preserved between ancient dunes when rainstorms

triggered mud flows down the slopes. On the slope faces, dinosaur tracks were

found going uphill, as footprints preserved on dune faces most often are. Interestingly,

a modern analog in many ways to the Cretaceous environment of Mongolia might

now be found in Arabia Felix, in the dunes and interdunes around Marib.

The impression is that he was not overly fond of Marib as a town, although Novacek

does provide a Web address in the notes to lead the reader into the archaeological

wonders of Yemen, and he mentions the archaeological ruins protruding from the

sand around Marib.

Novacek notes the threat commercial collectors pose to the paleontological resources

of Mongolia. One can only imagine what we would not know had the resources been

sold off and had the American Museum not built a long history of fieldwork and

study in Central Asia.

What will we lose if access to the field and its study is removed for shortsighted

gain? It gives pause to contemplate the responsible management of fossil resources

on public lands in the United States, a great concern to the paleontological

profession, to museums, and to the broader paleontological and educational communities.

The book closes with a consideration of the value of paleontology to humanity,

specifically the perspective it gives to extinction and the current biodiversity

crisis. While few pages are devoted to the topic, I consider this one of the

most important parts of the book because it is profound. Certainly, extinction

would be viewed differently if we had no fossil record; even if, as Novacek

points out, we do not need fossils to know about the current biodiversity crisis

and its causes. I would add two other contributions of the fossil record in

this solemn vein. Firstly, the fossil record contributes significantly to our

understanding of evolution and tangibly to the recognition that all biological

variations, physical or otherwise, are trivial compared to the realization that

we all share a common ancestor and a common history.

Secondly, fossils remain the primary data for determining time and place in

Earth history.

Now, with concerns of global warming looming large, the fossil record is invaluable

in documenting intervals of climatic anomaly. A case in point derives from Novacek’s

work in Baja. He and his team were focused on correlating early Eocene fossil

localities, including those on Ellesmere Island. That locality, above the Arctic

Circle, contains alligators and other warmth-loving creatures, and therefore

provides certain indication of a warmer global temperature compared to now.

The fossil record is instrumental in establishing boundary conditions for understanding

past climates and avenues for investigating the mechanisms of climate change.

More importantly perhaps, paleontology brings the uniqueness of our times into

focus. Now is the first time in Earth history humans have been subjected to

extensive global change precipitated by us and over which we have control.

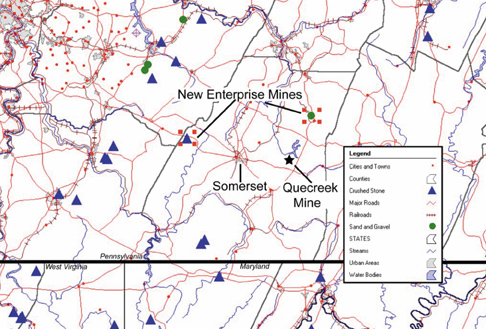

The

rescue of nine coal miners trapped in a flooded shaft in Somerset, Pa., in July,

involved dozens of agencies and organizations, with hundreds of people pooling

their resources. One of those people was Val Tepordei, and he didn’t even

know it. His efforts to create an Aggregates Industry Atlas CD four years ago

enabled nearby local quarries to aid in the Quecreek mine rescue.

The

rescue of nine coal miners trapped in a flooded shaft in Somerset, Pa., in July,

involved dozens of agencies and organizations, with hundreds of people pooling

their resources. One of those people was Val Tepordei, and he didn’t even

know it. His efforts to create an Aggregates Industry Atlas CD four years ago

enabled nearby local quarries to aid in the Quecreek mine rescue. |

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |