Krakatoa

by Simon Winchester.

HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 0 0662 1285 5, Hardcover, $29.95.

Thomas Wagner

Check out this month's On

the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The

popular Geomedia feature now available by topic.

Book Reviews:

Krakatoa

DVD:

Revisiting The Core

Maps:

Annotated list of references for geologic mapping in Iraq (supplemental information for the October issue

of Geotimes)

|

Krakatoa |

Two parts history, one part travel writing and one part popular science, Simon

Winchester’s Krakatoa is an enjoyable and informative read. Like

his very popular book The Map That Changed the World, which discusses

William Smith and his now-famous 1815 map, Winchester’s latest work reflects

his earth science roots; he majored in geology at Oxford. But this time, he

focuses on a non-human subject — Krakatoa volcano on an island in Indonesia.

Krakatoa’s 1883 eruption is one of the largest on historical record, killing

more than 34,000 people and reducing the island to one-third its original size.

The eruption is also notable for captivating world attention and highlighting

the growing interconnectedness of the global village. Krakatoa’s eruption

was one of the first major disasters widely broadcast through undersea telegraph

cables; its effects were observed worldwide through global cooling, spectacular

sunsets and sounds of the explosion heard up to 2,700 miles away. The eruption

also provided a deadly demonstration of the indirect hazards of volcanic eruptions,

such as tsunamis, and the near sterilization of the island made it a key site

for biologic studies of colonization.

Recent popular books on volcanoes, such as Volcano Cowboys by Dick Thompson

or the competing books on the Galeras disaster by Victoria Bruce and Stanley

Williams, concentrate on the human drama of volcanologists at work. Winchester

has set about a more difficult task, focusing on the volcano itself; I’m

surprised at the book’s popularity, with strong reviews and high sales

rankings on Web-based bookseller sites.

Winchester begins Krakatoa with a brief history of Indonesia, emphasizing

the development of trade, Dutch administration of the former colony and Islam.

He then spends considerable time developing a context for the eruption —

including descriptions of contemporary scientific knowledge, undersea telegraph

cable systems and life in the region. The eruption itself occupies the middle-third

of the book, and Winchester does his best to describe it from all possible perspectives

— ships at sea showered with pumice, shut-in Dutch expatriates watching

earthquake ripples in their water barrels and villagers on the beach running

for their lives from tsunamis. The final chapters discuss current geologic knowledge

and biologic studies of the island, as well as the role of the eruption in the

rise of militant Islam in Indonesia.

Krakatoa is not a perfect book. Written in chronologic order but organized

by subject, some chapters feel redundant and disjointed. And though at times

brilliant, the writing can be overly or inappropriately descriptive. Krakatoa’s

eruptions, for example, are described as the volcano having “lifted its

skirts.” As a consequence, complex geologic points can be difficult to

follow. The book also goes to great lengths to describe the 1883 eruption from

different perspectives, perhaps to illustrate the conflicting pictures portrayed

by first-hand accounts. Some editing and correlations would have made these

more accessible, as would a single map of key locations and events.

Geology comes up multiple times, including especially lengthy and variably relevant

descriptions of plate tectonic theory and its development. In these sections,

several factual errors stand out, particularly a glaring one regarding rock

magnetism. The book also exaggerates certain concepts, such as the misconception

that “seismically caused cracks in the earth swallow people.” Other

problems include the omission of important information such as the optical and

other atmospheric effects of volcanic sulfur, and a lack of contemporary information

on subduction-zone volcanology. Winchester affords scant discussion to the modern

Krakatoa work of Haraldur Sigurdsson and the book Krakatau, 1883: The Volcanic

Eruption and Its Effects, by Tom Simkin and Richard Fiske. The insight of

these and other scientists could have played a more prominent role in the text

and figures, some of which are clearly derivative but lack primary citations.

In fact, Winchester points out near the book’s end that his copy of Simkin

and Fiske’s work has been “thumbed through to the point of destruction.”

Unimpressed, Simkin and Fiske’s critical review of Winchester’s book

in the July 4 Science focuses almost wholly on the work’s scientific

shortcomings.

Although these errors and omissions are significant and could have been easily

corrected, they will not seriously mislead or detract from the experience of

the lay reader. The most important scientific point, that volcanism at Krakatoa

is caused by subduction of a tectonic plate, comes across clearly. Geologists

and teachers will need to ignore some of the erroneous details, but they will

find the vivid descriptions of eruptive events interesting and useful. The history

and global context of the eruption will engage readers, returning them to 1883

to experience it all firsthand and understand why it still captivates the world.

The relationship of the eruption to the rise of Islam is also well described

and not overstated, as popular works often do.

Winchester suggests that, in order to foment rebellion, the mullahs held up

the eruption as an example of God’s displeasure — carefully discussing

it within the context of local events and Dutch colonial excesses. Readers interested

in these historical aspects might also enjoy Pamela Swadling’s Plumes

from Paradise: Trade Cycles in Outer Southeast Asia & Their Impact on New

Guinea & Nearby Islands Until 1920 or David Keys’ Catastrophe,

which contends that a sixth century eruption in the vicinity of Krakatoa redefined

the world order.

On a final note, much of the book’s writing is a pleasure to read. Other

works often describe natural phenomena with dry terminology; however, Winchester’s

colorful descriptions leave the reader with the impression that he thoroughly

enjoyed writing this book. It will suffuse anyone with a sense of wonder about

Earth and its volcanoes, as well as offering a clear example of how the steady

march of science — in this case, plate tectonic theory — can help

us understand our world. In this time when the creationism debate is rearing

its ugly head again, I can only hope to see more books such as Krakatoa

written and read.

In The Core,

Earth’s core has stopped “spinning” thanks to a secret government

screw-up. As a result, the planet’s magnetic field begins to weaken, causing

all sorts of problems. People die suddenly, birds become navigationally inept,

and compasses drift off course. In one of the best scenes of the movie, Major

Beck Childs (Hillary Swank) helps save the shuttle Endeavor from crashing into

downtown Los Angeles by using old-fashioned geometry, a map and a pencil to

plot a better landing course.

In The Core,

Earth’s core has stopped “spinning” thanks to a secret government

screw-up. As a result, the planet’s magnetic field begins to weaken, causing

all sorts of problems. People die suddenly, birds become navigationally inept,

and compasses drift off course. In one of the best scenes of the movie, Major

Beck Childs (Hillary Swank) helps save the shuttle Endeavor from crashing into

downtown Los Angeles by using old-fashioned geometry, a map and a pencil to

plot a better landing course.

Childs then joins our hero, geophysicist Josh Keys (Aaron Eckhart), to help

save the planet itself. The two are part of a team of “terranauts”

who must drill their way to the interior of Earth and set off nuclear bombs

in its outer core. This, they believe, will return the core’s natural “spin”

and reset the magnetic field. As they begin their journey, the weather takes

a turn for the worse and the unusual. Beautiful auroras are seen every night

in Washington, D.C., for example, and lightning storms ravage cities around

the world. The threat of solar radiation burning the planet to cinders begins

in San Francisco.

Joining me at the movies was Director emeritus Hatten Yoder from the Geophysical

Laboratory of CIW, who admitted he hadn’t seen a movie in a theater in

more than 15 years. From CIW’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism was

post-doc Steven Hauck and staff members David James and Alan Linde, whose wife

Caroline also joined us.

As we bought a bucket of popcorn to share, James explained his criteria for

a quality science fiction film. “The primary requirement for a good science

fiction movie is one leap of faith,” he said. “Once you accept that,

everything else bridges scientifically, logically and consistently. Otherwise

the movie doesn’t seem believable.”

That didn’t bode well for The Core, but James was willing to give

it a go.

The lights in the theater dimmed and Yoder turned to whisper, “I hope these

people brought their asbestos suits. It gets hot down here,” in the core.

Indeed, 3,500 degrees Celsius, he added.

The Core begins in London with a series of unexplained deaths and a dramatic

frenzy of pigeons in Trafalgar Square. Then the scene turns to geophysicist

Josh Keys at the University of Chicago. “Sound waves lose frequency as

they travel through denser material,” he says to a classroom of students.

What was that, Keys? “I think he was referring to attenuation,” Linde

explained after the movie. “But you can’t change frequency, just amplitude.”

Uh-oh, not even 10 minutes into the show and the leaps of faith are starting.

No wonder Keys’ Geology 101 students are falling asleep or doing their

nails.

Thankfully the FBI pulls Keys from his class to bring him and his French buddy

Serge Levesque (Tcheky Karyo) — who we learn later is not only a biochemist,

but also an atomic weapons expert — in to help them explain the mysterious

deaths and cool Hitchcock-like pigeon behavior. As it turns out, only people

with pace-makers died.

Back in the geology office, a graduate student explains the bird-storm phenomenon:

“Ions in birds’ brains align with the magnetic field on Earth.”

Remember that sentence. I’m not certain, but I think it is the only time

in the movie where Earth’s magnetic field is not mistakenly referred to

as an electromagnetic field. This inaccuracy irritated the Carnegie geophysicists

throughout the film.

The movie takes its time developing the characters before throwing them together

to adventure into Earth’s outer core. When the mission begins, the movie

provides its own perspective on what the Earth’s interior might look like

and how these brilliant people with varying backgrounds might interact. ...

What are some leaps of faith that the movie demands?

| * A spinning core generates Earth’s magnetic field. That’s only partially right. Convection currents in the liquid part of the outer core do the job. As long as Earth is spinning, its core is spinning too; some scientists think it even spins a little faster than Earth. * An element called unobtainium cannot only withstand increasing temperatures and pressures, but also gets stronger in the process. As the movie recognizes, this element is unobtainable. * The temperature in Earth’s interior is 9,000 degrees. That’s heating it at least a thousand degrees more than most scientists would agree for Fahrenheit. The Core's Web site is more accurate. * Without the magnetic field, solar winds and radiation would torch everything on the surface of the planet. They might increase mutation rates, but they wouldn’t burn skin in seconds or melt steel. * The mantle is partially molten. Sorry, solid as a rock. Yes, it does move — about as fast as fingernails grow. * The magnetic field would shut down in a year. Geologic records show it takes hundreds to thousands of years to reverse the magnetic field, and that it has switched many times without destroying the planet’s surface. Of course, if a secret government act destroyed the core’s ability to produce a magnetic field, all bets are off. |

Did the movie get anything correct?

“The core is about the size of Mars,” Hauck said.

The thicknesses of the crust, mantle and core were also on target, and as far

as fruit goes, a peach is a pretty good analogy to Earth. All agreed, too, that

the scene with the shuttle is the best one in the entire movie — although

I would have to watch it again to check that Major Childs got her latitude and

longitude correct. In reality, the Los Angeles River is between 33 and 34 degrees

north latitude and at 118 degrees west longitude. If anyone else goes to see

this movie, please let us know what she scribbled down as the latitude and longitude

for the landing. The Carnegie geophysicists and I aren’t interested in

watching The Core twice.

Christina Reed

Links:

The Core’s Web

site

Back to top

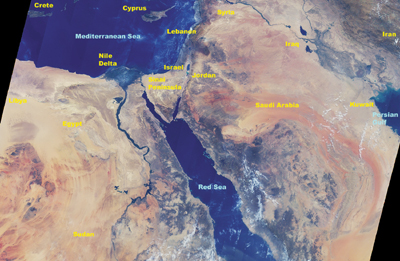

Geologic

Map of Iraq: Directorate General of Geological Survey and Mineral Investigations

by Z. J. Saad, H.H. Dikran and A.J., Hishaim (Bagdad). 1986. 1:1,000,000 scale.

Geologic

Map of Iraq: Directorate General of Geological Survey and Mineral Investigations

by Z. J. Saad, H.H. Dikran and A.J., Hishaim (Bagdad). 1986. 1:1,000,000 scale.

A general geologic map keyed to named stratigraphic units typically without

lithologic descriptions; the base map consists of major drainages and roads,

which were found to have some internal distortion.

Tectonic map of Iraq: Directorate General of Geological Survey and Mineral

Investigations by T. Buday and S.Z. Jassim (Bagdad).1984. 1:1,000,000 scale.

A general tectonic map showing fold belts and basins; the base map consists

of major drainages and roads, which were found to have some internal distortion.

Geological map of Iraq and southwestern Iran by Robertson Research International.

1987. 1:1,000,000 scale.

Derived from the maps listed above, but reinterpreted with satellite imagery

(LANDSAT); general lithologies are described.

Groundwater resources of Iraq, provisional regional maps: Development Board,

Ministry of Development, Government of Iraq by Ralph M. Parson Company (Los

Angeles). 1957. 1:1,680,000 scale.

A folio of neatly hand-drawn maps including physiographic, generalized geologic

(with brief lithologic descriptions), topographic, isohyetal, piezometric, isosalinity

and nitrate ion distribution maps; the base map consists of major drainages

roads.

Exploratory soil map of Iraq: Division of Soils and Agricultural Chemistry,

Directorate General of Agriculture research and Projects, Ministry of Agriculture

by P. Buringh (Bagdad). 1957. 1:1,000,000 scale.

Soil units have brief physiographic descriptions; the base map consists of major

drainages and roads.

Geology of Iraq: a bibliography from 1968 to 1988. Journal of Geological

Society of Iraq, 1988. v.21(1).

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |