Geotimes

Untitled Document

Geomedia

Geotimes.org offers

each month's book reviews, list of new books, book ordering information and new

maps.

Check out this month's On

the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The popular

Geomedia feature now available by topic.

Television:

Local TV makes learning geology fun

Book Reviews:

Gorgon: Paleontology, Obsession, and the Greatest Catastrophe

in Earth’s History

Movies:

Baffling flash-frozen science Plus, a Web exclusive:

Mixed media message

Television

Local

TV makes learning geology fun

On any given

night, most television viewers across the United States can find a documentary

that encompasses some aspect of geology. The program of choice could be a Science

Channel show on volcano chasers, a Discovery Channel show about the last Ice

Age in North America or a National Geographic Channel piece on asteroid impacts

on Earth. If viewers want a dose of science in their primetime viewing, these

hour-long programs are about the only choices. Viewers in North Texas and the

San Francisco Bay Area, however, have another option: local geology on local

television stations.

On any given

night, most television viewers across the United States can find a documentary

that encompasses some aspect of geology. The program of choice could be a Science

Channel show on volcano chasers, a Discovery Channel show about the last Ice

Age in North America or a National Geographic Channel piece on asteroid impacts

on Earth. If viewers want a dose of science in their primetime viewing, these

hour-long programs are about the only choices. Viewers in North Texas and the

San Francisco Bay Area, however, have another option: local geology on local

television stations.

Todd Kent shoots Devin Dennie discussing

local geology for an upcoming episode of GeoAmerica. Image courtesy of

Wayne Newman.

North Texas Explorer and Down to Earth are two half-hour-long

television programs that explore the geology of Texas and California, respectively.

The geologist-producers of both shows began their field-trip-style programs

to entertain and educate the general public — to bring geology into peoples’

homes and show them that geology is fun.

Geology on Texas

TV

“We looked around and wondered, ‘why isn’t there a recurrent

field-trip-style earth science and history show on TV?’” says Devin

Dennie, a geologist from Texas who is currently in a Ph.D. program at the University

of Oklahoma, and producer and star of North Texas Explorer. “We

felt there was a niche for this, teaching the general public how geology affects

our everyday lives,” he says. So a few years ago, when Dennie was in a

geology master’s program, he and his childhood friend, Todd Kent (who was

finishing up a degree in television and video production), got together to create

the show.

Originally aired on the University of North Texas television station, North

Texas Explorer aims to teach people just how significant geology is in day-to-day

living, Dennie says. For example, they recently taped shows at an ice cream

festival and at a Texas Rangers baseball game. While the connections might not

be blatantly obvious, Dennie says, geology is a big factor. “To make ice

cream, you use rock salt,” he says, “and right there you have geology.”

At the Texas Rangers baseball stadium, they explained how the Texas granite

used in the building’s construction formed millions of years ago. The show

has also covered more “serious” topics such as how oil ended up in

Texas. Regardless of the topic, Dennie and Kent seek to keep the show light,

often tying in mountain-biking or rock-climbing options to the area they are

teaching about. “Geology is in everything and is everywhere,” Dennie

says. “Our goal is to hold your attention long enough to teach you something

about it.”

At first, doing the show was a hobby. “But the more we did it, the more

we realized that people were watching it and actually liking it — it was

filling a need in the community.” So he and Kent decided to step it up

a bit after graduation. They teamed up with friend and photographer Wayne Newman

and found a professional media company to help produce the show so they could

reach a larger audience, but they still do most of the work themselves, including

the scriptwriting, on-camera hosting and narration, filming and editing.

North Texas Explorer has been seen on 10 stations across northern Texas

and New Mexico. The producers are now taking on a more national scope in the

form of a new program called GeoAmerica — a travel show that focuses

on “earth science heritage” across the country. They have already

shot several episodes and are hoping to produce more once funding is secured.

“Our goal is to broadcast this nationally and to eventually cover all 50

states,” Dennie says.

California geology

celebrities

For geologists

Mel Zucker and Richard Lambert in California, Down to Earth also started

as a hobby. The two are geology professors at Skyline College, a community college

in San Bruno, Calif., in the Bay Area. They wanted better images and educational

material for their geology classes, Zucker says, “so we started making

our own.” They began doing multimedia presentations in class in the 1970s,

Lambert says. “We used to set up six or eight slide projectors and show

all kinds of slides, as if we were on a field trip,” he says. As technology

advanced and became more readily available, the two moved into the video realm.

The professors now use the 30-minute programs in their classes as well as showing

them on two cable-access channels in the Bay Area.

For geologists

Mel Zucker and Richard Lambert in California, Down to Earth also started

as a hobby. The two are geology professors at Skyline College, a community college

in San Bruno, Calif., in the Bay Area. They wanted better images and educational

material for their geology classes, Zucker says, “so we started making

our own.” They began doing multimedia presentations in class in the 1970s,

Lambert says. “We used to set up six or eight slide projectors and show

all kinds of slides, as if we were on a field trip,” he says. As technology

advanced and became more readily available, the two moved into the video realm.

The professors now use the 30-minute programs in their classes as well as showing

them on two cable-access channels in the Bay Area.

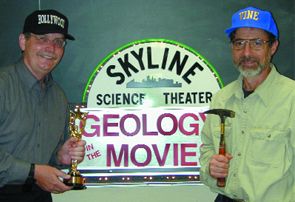

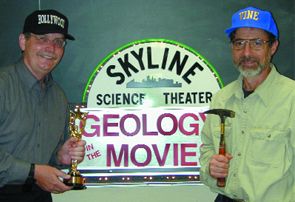

In San Francisco, geologists Richard “Hollywood”

Lambert and Mel “Vine” Zucker review geology in the movies for their

award-winning public access television series Down to Earth. Image courtesy

of Pat Carter, Skyline College.

Through the show, Zucker and Lambert have educated and entertained the public

and their students about topics near and dear to Californians: gold mining,

marine biology, coastal erosion, and of course, plate tectonics and seismology.

They have collaborated with and interviewed a number of geologists at the U.S.

Geological Survey (USGS) in Menlo Park, as well as geologists and engineers

from across the country.

Lambert and Zucker say that their students seem to like the movie review episodes

best. In the reviews, the geologists, in a parody of national movie review shows,

sit in director chairs and explain how the moviemakers “got it right or

blew it completely,” Zucker says. They have covered The Core and

Dante’s Peak, among others.

The team has produced more than 45 shows so far, with more in the works, such

as a four-part series commemorating the centennial of the 1906 earthquake in

San Francisco. The 1906 temblor, Lambert says, marked the beginning of modern

seismology. “It’s important for people to understand the history and

the science of it,” he says.

Zucker and Lambert are “providing a tremendous service to the community

and really ought to be applauded,” says Mary Lou Zoback, a seismologist

at USGS in Menlo Park who has been interviewed for the 1906 series. Working

with the two has been great, she says, as they ask excellent questions and then

“skillfully extract the parts of what we discussed” to produce a very

professional show. This type of program is “absolutely something that should

be done elsewhere,” Zoback says.

“With all the new technology and editing possibilities on your desktop

computer, anyone anywhere could do this and I think it would be great,”

Lambert says. Making the videos, however, is quite time-consuming. Lambert and

Zucker teach full-time and produce the show on nights, weekends and semester

breaks. It takes them anywhere from one to seven months to produce one episode.

“It’s a labor of love and expense,” Lambert says, “but it’s

very satisfying.”

Megan Sever

Links:

North

Texas Explorer

GeoAmerica

Back to top

Book Reviews

|

Gorgon: Paleontology, Obsession, and

the Greatest Catastrophe in Earth’s History

by Peter D. Ward.

Viking Books, 2004.

ISBN 0670030945. Hardcover, $27.95.

|

Extinction realities

Spencer G. Lucas

“Gorgon” is short for “gorgonopsian,” a lion-sized reptilian

predator of the Late Permian, known primarily from fossils found in the Karoo

basin of South Africa. The book Gorgon is an autobiographical account

of Peter Ward’s quest, beginning in the early 1990s, for an answer to what

caused the supposed mass extinction of land vertebrates at the Permian Triassic

boundary (P/T).

So, how did Ward, whose primary research during the 1980s was on Late Cretaceous

ammonites, become involved in the study of the nonmarine P/T extinction? Quite

simply, it was because he needed a large scientific problem to solve. For, as

Ward tells us, once he and others established that an asteroid impact caused

a sudden end-Cretaceous mass extinction, he went looking for a new and equally

challenging scientific problem.

Much of the book recounts how Ward met this challenge, with diary-like accounts

of his fieldwork in the Karoo basin, mostly in collaboration with Roger Smith

and his co-workers at the South African Museum. These accounts stress the hardships

and rewards of fieldwork in the Karoo, and reveal many of the ups and downs

of the people, their work and the scientific process. I think these accounts

are the best part of this book, although fieldwork in the Karoo does not sound

much different than working in dry and remote badlands regions, such as those

that are common in New Mexico or Wyoming.

The rest of this book weaves into the field accounts a progression of discovery

and reasoning that should lead us to the cause of the P/T extinction that Ward

advocates. However, this part of the book is not well-developed; he reveals

little explicit information about evidence of the P/T extinction. The scientific

process here is difficult to follow — a difficulty exacerbated by internal

inconsistency and questionable scientific reasoning.

For most of the book, Ward characterizes the P/T extinction as “a sudden

and catastrophic event” or “a message of rapid catastrophe,”

only to later state that “many lines of evidence were converging on something

more prolonged than a single quick strike.” Ward’s last word, however,

is that the P/T mass extinction leads us to a new view of extinction as “fast,

and in pulses. Not a single short burst of death ... but instead a series of

episodes of extinction, for perhaps a hundred thousand years.” How, however,

the reader of the previous couple hundred pages, filled with various, inconsistent

descriptions, can grasp or in any way evaluate the data behind his conclusion

eludes me.

Even more problematic is Ward’s attempt to tie the P/T extinction to a

Triassic world of low atmospheric oxygen. Ward claims that Triassic red beds

(iron-rich sedimentary rocks) are evidence of (and indeed a cause of) the low

oxygen, as the “rusting” sediments sucked the oxygen out of the air.

However, isn’t the abundance of Triassic red beds (they are not omnipresent,

as Ward believes) evidence of relatively high levels of atmospheric oxygen?

Ward concludes that the “global rusting” caused two enormous catastrophes:

the Permian-Triassic extinction followed 50 million years later by the Triassic-Jurassic

extinction. Note, however, that Ward later dismisses the end-Triassic extinction

as unlike the P/T extinction because it was “never a threat to end animal

life on the planet.” Then, Ward goes a step further with this argument.

He uses the supposed low atmospheric oxygen levels of the Triassic to explain

the rise of the dinosaurs and their descendants, which followed the demise of

the mammal-like reptiles that dominated Permian landscapes. “I am proposing

that the dinosaurs and their descendants, the true birds, came about as a result

of low oxygen,” he writes, noting that he is the first to propose such

a mechanism. However, the large lungs of birds (and perhaps of dinosaurs) are

oxygen-hungry structures designed to supercharge the avian circulatory system

by rapidly oxygenating the blood. They are exactly the opposite of what would

evolve in a low-oxygen world. Animals that evolve in low-oxygen environments

do not evolve structures designed to use large quantities of oxygen.

Gorgon is readily recognized as a book of popular science meant to be

read primarily by the layperson. I believe such books should present well-reasoned

and well-documented science to their readers. This book does not. Gorgon

tells us much about what Peter Ward did during the 1990s, but its contribution

to a scientific understanding of the end-Permian extinction is a disappointment.

Lucas is curator of paleontology

and geology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History. E-mail: Slucas@nmmnh.state.nm.us.

Back to top

Movies

Baffling flash-frozen science

Sidebar: Mixed media message

In the epic

disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow, hurricanes, tornados and hail

pummel different parts of the planet. The entire Northern Hemisphere ends up

covered with snow and ice. Although the special effects make it look like the

real thing, many of the scientific flaws in this enjoyable movie are all too

easy to recognize. If you want some suspense when you watch the DVD, to be released

this month, read no further — we are about to embark on a little investigation

into the science (or lack therereof) behind the film.

In the epic

disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow, hurricanes, tornados and hail

pummel different parts of the planet. The entire Northern Hemisphere ends up

covered with snow and ice. Although the special effects make it look like the

real thing, many of the scientific flaws in this enjoyable movie are all too

easy to recognize. If you want some suspense when you watch the DVD, to be released

this month, read no further — we are about to embark on a little investigation

into the science (or lack therereof) behind the film.

A highly exaggerated storm surge floods

New York City in The Day After Tomorrow, a movie that while entertaining,

bends several laws of physics in its dramatization of sudden climate change.

Image courtesy of 20th Century Fox.

The blockbuster’s opening sequence shows a team of scientists, led by paleoclimatologist

Jack Hall (Dennis Quaid), living through an Antarctic ice shelf collapse (in

a digitally recreated sequence reminiscent of the disintegrating Larsen B Ice

Shelf in 2002). After offscreen analysis of cores from the shattered shelf shows

evidence of an abrupt climate change 10,000 years ago, Jack tries to persuade

policy-makers that something incredible is about to happen.

The movie briefly addresses the trigger for the imminent climate shift, showing

Jack standing before a graphic of Wally Broecker’s ocean conveyor belt

at a United Nations gathering. The release of fresh water at high latitudes

from melting glaciers, he says, will lead to a “critical desalinization

point,” slowing down Atlantic circulation, which affects the Gulf Stream

— and the weather.

|

What did you think of the movie The Day

After Tomorrow?

E-mail your reactions, scientific observations and other comments to Geotimes

at geotimes@agiweb.org.

|

To prove his point, snow falls on Delhi, massive storms strike Hawaii, football-sized

hail kills pedestrians in Tokyo and unbelievable tornados destroy Los Angeles.

Jack runs models of a brewing “megastorm” over the Arctic, showing

three conjoined storms — hurricane-looking cloud masses with incredibly

cold eyes — traveling south, dumping snow and flash-freezing the planet

(and people) as it goes.

While the scientists work, the movie follows the somewhat formulaic path of

a summer disaster flick, doling out stock characters and tiny glimpses of human

drama. One plotline follows Jack’s son Sam (Jake Gyllenhall) and his schoolmates,

trapped in New York City directly in the path of one of the freezing storm eyes.

They witness the inundation of New York, which then freezes solid as the megastorm

passes. Jack and his co-workers, well-versed in traveling in Antarctic conditions,

set out to find Sam as the climate continues to change ... you’ll have

to watch the movie to find out what happens next.

“It’s not often that you get a movie starring an ice-climbing paleoclimatologist,”

Jonathan Overpeck of the University of Arizona told a packed house of paleoclimatologists,

at the first annual CLIVAR meeting on abrupt climate change in May in Baltimore,

Md. “There is some good science behind this movie, like all good science

fiction.”

But a truly good sci-fi film, says Gerry Stokes, director of the Joint Global

Change Research Institute of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the

University of Maryland, College Park, is as close to reality as possible, with

suspension of only one or two rules of conduct, “like the ability to travel

faster than the speed of light.” This movie “had to have a lot of

things go wrong.”

For example, Stokes points out that cores from the Antarctic ice shelves would

be too young to contain a climate record of 10,000 years, something normally

extracted from Greenland or Vostok ice cores. Also, seasonal Atlantic freezing

and thawing would extend the glacial shift over 10 years, not 10 days. And even

though the weather teleconnections across the globe are plausible, Stokes says,

the movie’s ensuing flash-freezing megastorm is not.

These events, Stokes says, break some very big rules: the first and second laws

of thermodynamics. The megastorm’s eyes are supposed to be large super-cooled

air masses, at negative 150 degrees Fahrenheit, which Stokes says is about 100

degrees colder than the coldest point in Earth’s atmosphere. Moving air

that cold that quickly requires the release of energy — in other words,

heat. “To quick-freeze something that way,” Stokes says, “doesn’t

happen.”

The movie breaks other physical rules as well, says Klaus Jacob, a senior researcher

at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, in Palisades, N.Y., by exaggerating the

flooding of New York by at least an order of magnitude. Using the Statue of

Liberty as a gauge, Klaus says the movie shows about a 200-foot storm surge.

“A 30-foot surge,” he says, “would be what one could expect under

the worst of circumstances.”

Regardless of the movie’s trespasses, it does highlight some current geoscience

issues. “Independent of the movie, there has been modeling of increased

inputs of fresh water” to the Atlantic, says Tony Busalacchi, director

of the Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center at the University of Maryland,

College Park. These “water-hosing experiments” show an ensuing Gulf

Stream deceleration, and heat stops transferring from lower to higher latitudes,

changing the way atmospheric moisture moves. “We need more work on this,”

he says, to model abrupt climate change and ocean salinity.

More work is also needed in communicating science, says Stokes, who was struck

by the movie’s portrayal of scientists interacting with policy-makers.

It was a “classic confrontation,” he notes, with “bullheadedness

on both sides,” leading characters to discount both valid science and policy

concerns.

“The movie is certainly sensationalistic,” Busalacchi says, “but

it does provide value in getting people to think about the climate.” And

despite all its faults, scientific and otherwise, the movie was highly entertaining.

The larger-than-life imagery of a quickly glaciating planet made it a relief

to look outside and find a warm, relatively ice-free planet.

Mixed

media message

When Steven Spielberg's movie Jaws came out in 1975, the shark thriller

spawned a generation of people afraid to go in the water. Anthony Leiserowitz,

a research scientist at Decision Research, a research institute in Eugene,

Ore., wanted to know if the movie The Day After Tomorrow might do

something similar for global climate change: Would it change how people

perceived the risk of climate change?

The team that produced the blockbuster special-effects movie meant to make a "popcorn" flick that also would raise public consciousness of global warming. In a series of national surveys, both before and after the blockbuster movie was released last May, Leiserowitz asked people how they thought about climate change and how they ranked global warming among national policy issues, among other questions. He also tracked media coverage of the movie, from entertainment, political and scientific perspectives.

After surveying 529 people, 139 of whom saw the movie, Leiserowitz concluded that movie seemed to have an impact: Statistical differences in opinion on climate change existed between those who had and had not watched the movie. The movie's watchers were more likely than those who hadn't seen it to believe that climate is stable within certain limits, and that in the next 50 years, global warming would bring more intense storms, flooding, food shortages and other impacts.

Those polled who saw the movie also answered that they intended to be more politically active on global warming issues or take personal actions on their own. In the end, however, the majority of both watchers and nonwatchers said they were more concerned about global warming, but did not spend much time worrying about it.

These survey results will be published in the November issue of the journal

Environment. Leiserowitz's report also includes an analysis of media

coverage of movies and news events around the same time period, such as

Fahrenheit 9/11 and news from Iraq, compared with that of The

Day After Tomorrow.

Although The Day After Tomorrow seemed to have its intended effect

in the United States, Leiserowitz says that his conclusions are tempered

by the short time period that the film was in theaters. He intends to follow

up on the surveys to see how long the sense of risk imparted by the movie remains with its audience.

NL |

Naomi Lubick

Link:

"Earthquakes, climate change and

reel disasters," Geotimes, September 2004

Back to top

Untitled Document

On any given

night, most television viewers across the United States can find a documentary

that encompasses some aspect of geology. The program of choice could be a Science

Channel show on volcano chasers, a Discovery Channel show about the last Ice

Age in North America or a National Geographic Channel piece on asteroid impacts

on Earth. If viewers want a dose of science in their primetime viewing, these

hour-long programs are about the only choices. Viewers in North Texas and the

San Francisco Bay Area, however, have another option: local geology on local

television stations.

On any given

night, most television viewers across the United States can find a documentary

that encompasses some aspect of geology. The program of choice could be a Science

Channel show on volcano chasers, a Discovery Channel show about the last Ice

Age in North America or a National Geographic Channel piece on asteroid impacts

on Earth. If viewers want a dose of science in their primetime viewing, these

hour-long programs are about the only choices. Viewers in North Texas and the

San Francisco Bay Area, however, have another option: local geology on local

television stations.

For geologists

Mel Zucker and Richard Lambert in California, Down to Earth also started

as a hobby. The two are geology professors at Skyline College, a community college

in San Bruno, Calif., in the Bay Area. They wanted better images and educational

material for their geology classes, Zucker says, “so we started making

our own.” They began doing multimedia presentations in class in the 1970s,

Lambert says. “We used to set up six or eight slide projectors and show

all kinds of slides, as if we were on a field trip,” he says. As technology

advanced and became more readily available, the two moved into the video realm.

The professors now use the 30-minute programs in their classes as well as showing

them on two cable-access channels in the Bay Area.

For geologists

Mel Zucker and Richard Lambert in California, Down to Earth also started

as a hobby. The two are geology professors at Skyline College, a community college

in San Bruno, Calif., in the Bay Area. They wanted better images and educational

material for their geology classes, Zucker says, “so we started making

our own.” They began doing multimedia presentations in class in the 1970s,

Lambert says. “We used to set up six or eight slide projectors and show

all kinds of slides, as if we were on a field trip,” he says. As technology

advanced and became more readily available, the two moved into the video realm.

The professors now use the 30-minute programs in their classes as well as showing

them on two cable-access channels in the Bay Area.

In the epic

disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow, hurricanes, tornados and hail

pummel different parts of the planet. The entire Northern Hemisphere ends up

covered with snow and ice. Although the special effects make it look like the

real thing, many of the scientific flaws in this enjoyable movie are all too

easy to recognize. If you want some suspense when you watch the DVD, to be released

this month, read no further — we are about to embark on a little investigation

into the science (or lack therereof) behind the film.

In the epic

disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow, hurricanes, tornados and hail

pummel different parts of the planet. The entire Northern Hemisphere ends up

covered with snow and ice. Although the special effects make it look like the

real thing, many of the scientific flaws in this enjoyable movie are all too

easy to recognize. If you want some suspense when you watch the DVD, to be released

this month, read no further — we are about to embark on a little investigation

into the science (or lack therereof) behind the film.