|

Travels in Geology September 2006, posted September 19, 2006

Summer roadtrip: A fossil aquarium in Wyoming

Callan Bentley, Geotimes contributing writer, has been traveling across North America in his Volkswagen Westfalia camper van this summer. From May to September, he traveled from Washington, D.C., up to central Alaska, and then back. When he came across areas with interesting geology, he used the van's solar power to plug into a laptop and fire off a dispatch for Geotimes. The following is Part 3 of his three-part roadtrip series.

For

years, I've been seeing Green River Formation fossils everywhere. Chances

are, you've seen them too. The ubiquitous, iconic and beautiful fossil

fish are found in nature stores, museums, private collections and geology

departments throughout America. Their abundance in nature makes the fish

among the least expensive vertebrate fossils.

For

years, I've been seeing Green River Formation fossils everywhere. Chances

are, you've seen them too. The ubiquitous, iconic and beautiful fossil

fish are found in nature stores, museums, private collections and geology

departments throughout America. Their abundance in nature makes the fish

among the least expensive vertebrate fossils.

Knightia is the

most common fossil in the Green River Formation of Wyoming. It is a small

fish in the herring family, preserved in mass die-off layers exposed at

Fossil Butte National Monument. All

photographs by Callan Bentley.

The size of a chocolate bar, a typical Green River Formation fossil fish looks like a dark brown etching on a tan background. The contrast in color is one of their most recognizable characteristics to the amateur collector, and professional paleontologists venerate them for their incredible detail. In most fish fossils, only bones are present, often strewn about in a disarticulated mess. But not so for Knightia (a herring, which is the most common Green River species) and its kin: They display scales, teeth and fins, all exactly where they would be in a living fish.

On

my return trip across the United States, I wanted to visit the source

of all these exquisite fossils. It turns out that they come from the southwestern

corner of Wyoming, near the Utah and Colorado state borders.

On

my return trip across the United States, I wanted to visit the source

of all these exquisite fossils. It turns out that they come from the southwestern

corner of Wyoming, near the Utah and Colorado state borders.

Fossil Butte National Monument

is located in southwestern Wyoming, near the town of Kemmerer. It is the

best place in the world to see freshwater lake fossils from 50 million

years ago.

An area of dry upland sagebrush today, the fossil site doesn't look like

a great place to go fishing. But 50 million years ago, during the Eocene

epoch, it was the center of a large aquatic ecosystem. Three large lakes

(including aptly-named Fossil Lake) laid down fine-grained siltstones

and freshwater limestones — sedimentary rocks that recorded the creatures

living there at that time. Fossil Butte National Monument,

near Kemmerer, Wyo., preserves some of the finest

exposures of the Green River Formation. The formation is named for the

modern-day Green River (a tributary of the Colorado River), which had

nothing to do with the deposition of the fossil-bearing rocks.

The

National Park Service maintains a free museum at the site, where visitors

may view some of the finest examples of local fossils. The museum features

some amazing examples of the diversity of life preserved at Fossil Butte.

Although fossil fish are the foot-soldiers of the Green River, the formation

also yields reptiles such as turtle and crocodiles, and at least one snake.

Other fossils show insects, crayfish and freshwater shrimp. It's remarkable

to see the fine details of these small, delicate organisms: antennae stretched

out for several inches, or the delicate lace of veins in a dragonfly's

wings. Leaves of shore-bound plants are also prevalent, especially sycamore

trees and fan-palms. Even flying creatures like birds and bats fell into

Fossil Lake and were preserved.

The

National Park Service maintains a free museum at the site, where visitors

may view some of the finest examples of local fossils. The museum features

some amazing examples of the diversity of life preserved at Fossil Butte.

Although fossil fish are the foot-soldiers of the Green River, the formation

also yields reptiles such as turtle and crocodiles, and at least one snake.

Other fossils show insects, crayfish and freshwater shrimp. It's remarkable

to see the fine details of these small, delicate organisms: antennae stretched

out for several inches, or the delicate lace of veins in a dragonfly's

wings. Leaves of shore-bound plants are also prevalent, especially sycamore

trees and fan-palms. Even flying creatures like birds and bats fell into

Fossil Lake and were preserved.

Palm trees surrounded Fossil Lake during the Eocene, and dropped in their leaves, where they became fossilized.

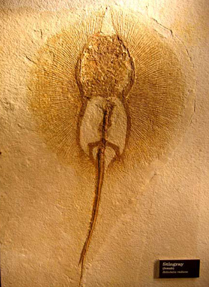

The amazing thing about Fossil Butte is this diversity: The Green River Formation preserves an entire ecosystem here. The fish fauna includes 25 species, ranging from small minnows to massive gars, which were 6 feet long and armored in giant diamond-shaped scales. There are even stingrays preserved in the sediments of Fossil Lake, though modern freshwater stingrays are restricted to the Amazon basin in South America. Many of the fish (and other organisms) are concentrated in particularly rich layers that show massive die-offs in the lake community. What caused these die-offs is not known, but is the subject of a short film detailing the work of several paleontologists who do field work at Fossil Butte.

Wandering

through the visitor center, I was struck by how complete a community was

displayed in the rocks. From the foundations of the food chain to the

highest predators, Fossil Butte gives us a unique snapshot of life in

the Eocene.

Wandering

through the visitor center, I was struck by how complete a community was

displayed in the rocks. From the foundations of the food chain to the

highest predators, Fossil Butte gives us a unique snapshot of life in

the Eocene.

The only snake known from the Green

River Formation is on display in the Fossil Butte National Monument Visitors

Center.

Also in the Fossil Butte visitor center, a preparator is hard at work

removing layers of rock from large specimens. The working space shares

a window with the visitors' realm, so curious tourists can ask questions

about how fossils are detailed for museum-quality display.

If the sun isn't too hot, several hikes offer another good way to take

in the site. One trail winds through the upland portion of the park, emphasizing

modern plants and animals. Visitors can also hike to the main area where

fossils are quarried. On Saturdays, the park offers an additional bonus:

a participatory program called an "Aquarium in Stone." With

the supervision of a park ranger, visitors help to quarry fossils between

10 a.m. and 3 p.m.

"We started it nine years ago, and it's increasing in popularity," says Arvid Aase, a specialist at Fossil Butte. "It's a great experience for them, and it's free." Because it is a national park, visitors cannot keep the fossils they quarry, but the rangers do issue a certificate bearing each sample's museum I.D. number, declaring that the visitor is responsible for contributing it to the collection.

The

Green River Formation is not limited to Fossil Butte National Monument,

however, which is only 13 square miles in extent. Several local commercial

operations work their own exposures of the rock outside the park. For

a fee, visitors can not only participate in the quarrying of fossils,

but they actually get to keep what they find. Of these commercial quarrying

operations, the closest to the park is Ulrich's Fossil

Gallery, located just off the park entrance road near Highway 30.

Ulrich's program lasts about three hours, and allows the visitor to keep

up to 10 fossil fish for a fee of $75. (The state of Wyoming retains any

"rare and unusual" fossils: stingrays, gar fish, mammals, birds.)

The commercial fossil quarries typically will square off your fossil finds

with their rock saws, making them more stable and attractive for display.

The

Green River Formation is not limited to Fossil Butte National Monument,

however, which is only 13 square miles in extent. Several local commercial

operations work their own exposures of the rock outside the park. For

a fee, visitors can not only participate in the quarrying of fossils,

but they actually get to keep what they find. Of these commercial quarrying

operations, the closest to the park is Ulrich's Fossil

Gallery, located just off the park entrance road near Highway 30.

Ulrich's program lasts about three hours, and allows the visitor to keep

up to 10 fossil fish for a fee of $75. (The state of Wyoming retains any

"rare and unusual" fossils: stingrays, gar fish, mammals, birds.)

The commercial fossil quarries typically will square off your fossil finds

with their rock saws, making them more stable and attractive for display.

Freshwater stingrays are known from Wyoming's Green River Formation, though today this group of fish is only found in South America.

If you don't have enough time to participate in a quarrying expedition,

Ulrich's and other Kemmerer-area rock shops have displays of their fossils

that rival the official display at Fossil Butte. It's worth stopping at

least one shop to check out the variety of petrified critters.

In addition, the park and local chambers of commerce have collaborated

on a scavenger hunt called "Fishing the Layers of Time." Participants

of all ages purchase a small booklet, and then follow clues to displays

in the Kemmerer area and make rubbings of various fossils. When the booklet

is complete, it may be redeemed for a small fish fossil.

And the area does offer more than just fossils, in case you're caught in the unenviable position of traveling with a nonpaleontologist: The original J.C. Penney store is in Kemmerer, and the local Oyster Ridge Bluegrass Festival entertains music lovers for three days in late July.

I found myself wishing for more time at Fossil Butte. On the return leg of my roadtrip, my schedule was focused on getting back to the comforts of home, but Fossil Butte has a special magnetism to it. Having stopped there and sampled the wealth of fossils, I found myself craving more. Were I to do it over again, I would schedule several days in the Kemmerer area. This is not merely the acquisitive urge to own fossils, but a real interest the act of discovery — the thrill that comes from cracking open a rock and seeing something no human has ever seen before.

Callan Bentley

Summer

roadtrip (Part 1): Driving to "West Dakota," Geotimes,

Travels in Geology, July 2006

Summer roadtrip (Part II): Ferrying

through the Inside Passage, Geotimes, Travels in Geology, August

2006

Fossil

Butte National Monument

Ulrich's

Fossil Gallery

Resources

from the Intermountain Natural History Association

Kemmerer,

Wyo., Chamber of Commerce

Subscribe

Subscribe